After 14 years of torture and illegal detention 'freed' Guantanamo prisoners are left destitute

KEY POINTS

- Freed prisoners face a lonely life of poverty in foreign countries where they have no friends, family or community.

- Many Guantanamo Bay prisoners were bought by the US from Pakistani and Afghan bounty hunters and militants.

In February 2016, Barack Obama unveiled his legacy with respect to Guantanamo Bay, the promised closure, which constituted a major plank of his presidential election campaign in 2008. The four-point plan will not end the indefinite and arbitrary detention of the men held there without due process rights but is intended to empty the current Guantanamo Bay prison facility, with the largest number of those who can be released being freed.

Earlier this month, it was revealed that due to the acceleration of prisoner reviews - an administrative process to determine whether or not prisoners designated to be held indefinitely can be released - more than 35 of the remaining prisoners, almost half of the prison's then population of 76 are cleared for release.

Barack Obama's administration took a further positive step on 14 August with the release of 15 prisoners to the UAE. In one day, the prison population fell by almost a fifth to 61. The 15 men, aged between 36 and 66, are 12 Yemenis and three Afghans. Many arrived at Guantanamo in their early 20s and have spent over 14 years in US detention without ever having been prosecuted for any crime.

Over 86% of Guantanamo prisoners were bought by the US from Pakistani and Afghan bounty hunters and militants, who rounded up their victims with little to no evidence they had links to terrorism.

The men are now effectively refugees, they have not been repatriated but sent to a third country that has agreed to resettle them. Due to the security situation and ongoing war, transfers to Yemen are currently banned and have not taken place since 2009. As a result, at least six of the Yemenis had been cleared for release for over 7 years, and in some cases, had been free to leave for over a decade, but had nowhere to go. No Afghans have been repatriated since December 2014.

Ironically, while US politicians have raised concerns about the possible security threat the release of these men poses to America, insecurity and instability fueled by the US's ongoing involvement in conflicts in Yemen and Afghanistan have made it impossible for the men to return home to their families. For some of the Yemenis, it has meant many unnecessary additional years spent at Guantanamo.

Nonetheless, speaking about her client Yemeni Zahir Hamdoun, who arrived at Guantanamo aged 22, lawyer Pardiss Kebriaei from the US NGO Center for Constitutional Rights said, "During a phone call before his release, Mr. Hamdoun said he felt happy and hopeful – a remarkable sentiment from a man who has lived through hell in Guantanamo and lost over 14 years of his life.

Despite the tiresome political fear-mongering around every detainee transfer, the reality is that men like Mr. Hamdoun want nothing more than to put this wretched chapter behind them and try to move on." The UAE resettled five other Yemenis in November 2015.

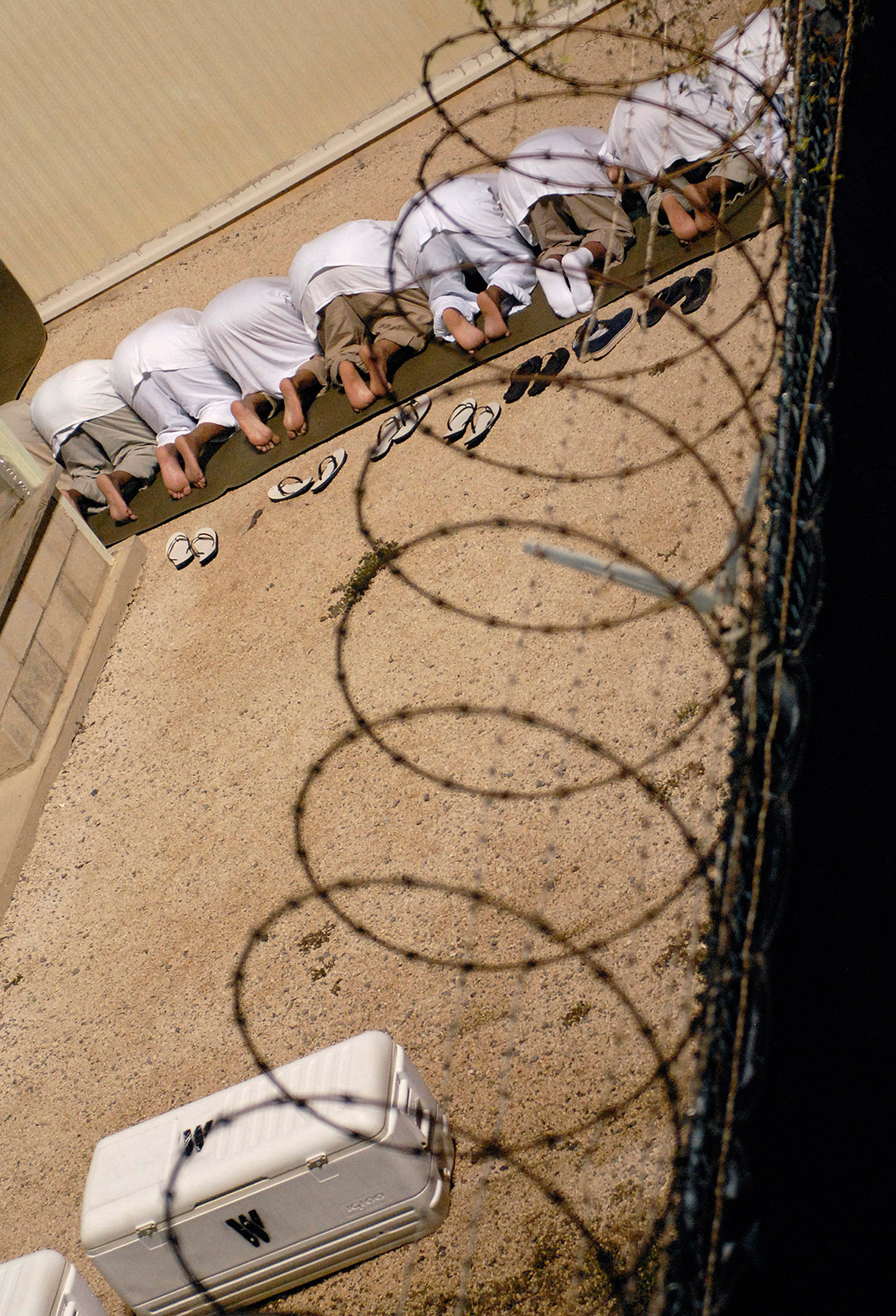

Inside Guantanamo Bay - life of captives in the notorious prison

With a further 20 prisoners also cleared for release, the Obama administration plans to transfer all of them by the end of the summer and reduce the prison population to around 40. Of the other prisoners, less than a dozen face charges in questionable legal proceedings. The Obama administration is keen to wash its hands of Guantanamo Bay and its prisoners, but little attention is paid to what becomes of the 'freed' prisoners.

In many cases, released prisoners find themselves subject to new restrictions on their liberty; freedom remains elusive, particularly for those who are resettled in third countries. In the UAE, those released there in 2015 have faced restrictions on contact with other people, and although they have been promised family visits, there is no evidence they have received any.

In other states, prisoners find themselves in new surroundings where they do not speak the language, have no friends and family, community, and may find themselves in situations of poverty or held in immigration detention as well as continuing to suffer the stigma of having been in Guantanamo once people find out who they are. The latter can continue to be a problem long after prisoners are released.

In May 2015, Yemeni Asim Thabit Abdullah al-Khalaqi, one of three prisoners released to Kazakhstan 6 months earlier, died of kidney failure. Inadequate medical care at Guantanamo and after release is alleged to have contributed to his death. As survivors of torture, all of the men should be guaranteed the right to rehabilitation facilities in the states they are sent to, but this is seldom provided.

Life for six men – all refugees from Syria, Palestine and Tunisia – resettled in Uruguay in 2014 has been particularly hard, with promises made of jobs, homes and family reunions having been broken, leading the men to protest outside the US Embassy in Montevideo in 2015.

Most recently, one of the men, disabled Syrian refugee Abu Wa'el Dhiab caused a media stir when he allegedly disappeared for several weeks and later resurfaced in Venezuela. The media claimed he was on the run and that he had travelled to Brazil where he posed a threat to the Olympics Games. No evidence has surfaced that he had gone to Brazil in the media-fabricated storm.

Instead, Dhiab is currently detained incommunicado in Venezuela pending deportation to Uruguay; he has been denied a lawyer and is effectively being held without charge as he was in Guantanamo. He had asked to be sent to Turkey or an Arab state where he can be reunited with his family stuck in war-torn Syria, another promise broken by the Uruguayan authorities.

After 14 years of torture and indefinite detention, among other human rights abuses, the US must ensure the safety of the men released and respect for their human rights, ensuring the conditions for their safe rehabilitation and reintegration into society, regardless of where they are released.

Aisha Maniar is a London-based human rights activist who works with the London Guantánamo Campaign and other organisations, mainly on issues related to prisoner and minority rights and torture.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.