Another Rwanda: Nearly half a million Rohingya Muslims have fled Myanmar in four weeks

The number of refugees arriving in Bangladesh since 25 August has been estimated at 480,000 – 60% of them children.

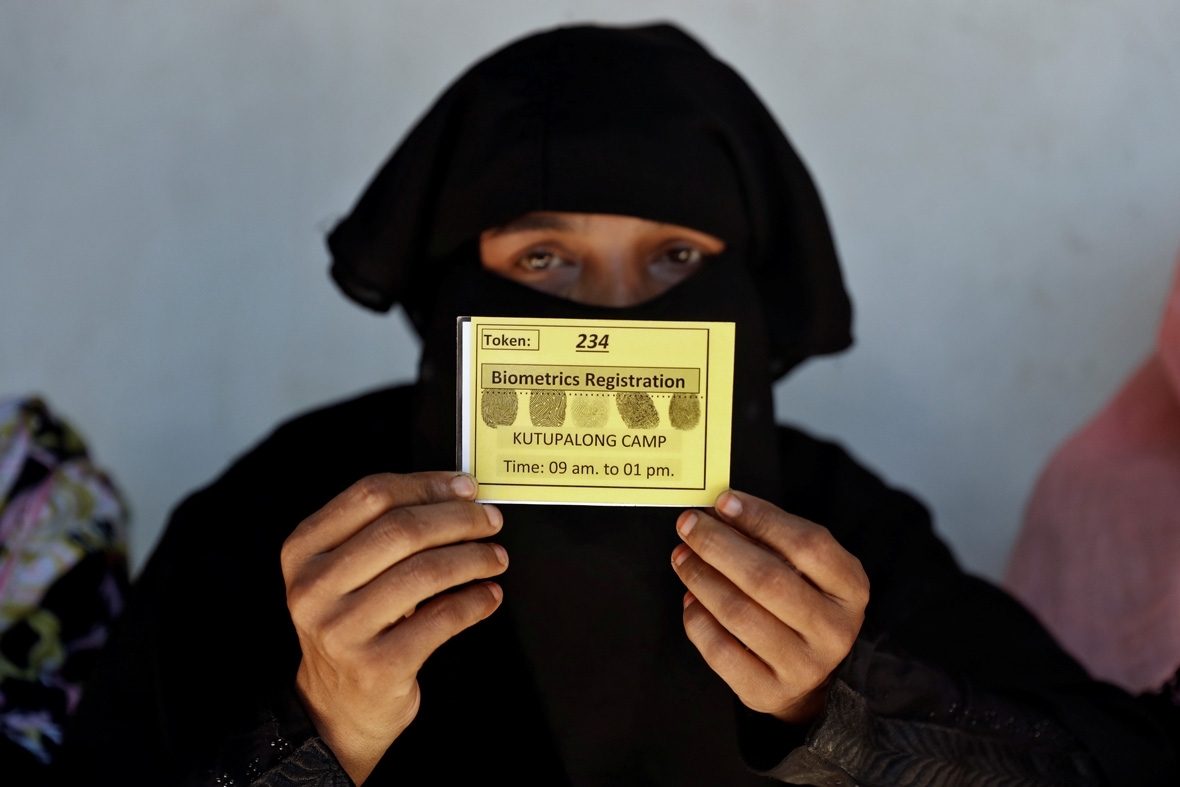

Nearly half a million Rohingya Muslims have fled from Myanmar into Bangladesh over the past four weeks. The number of refugees arriving in Bangladesh since 25 August has been estimated at 480,000 – 60% of them children. They have been fleeing violence that has been likened to the genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda.

On Tuesday (26 September) the United Nations drastically increased the estimated number of Rohingya Muslims who have fled violence in Myanmar. A report by UN agencies and international charities said the higher number was due largely to an estimated 35,000 Rohingya, not previously accounted for, moving into two refugee camps. It also said numbers crossing the border had started to rise again. After reporting a significant fall in arrivals last week, the new report said hundreds had been crossing the border daily in recent days.

Between the new arrivals and some 300,000 Rohingya who were already living in the area due to previous violence in Myanmar, there are now nearly 800,000 refugees in camps around the Bangladesh border town of Cox's Bazar that are bursting at the seams.

The speed and scale of the exodus from Myanmar has left hundreds of thousands living in dire conditions in a poor part of a poor country, and United Nations and aid agencies are scrambling to give people shelter, get them fed and prevent an outbreak of disease.

"The massive influx of people seeking safety has been outpacing capacities to respond, and the situation for these refugees has still not stabilised," Adrian Edwards, a spokesman for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, said in Geneva. "UNHCR is calling for a redoubling of the international humanitarian response in Bangladesh."

Action Against Hunger's Global Chief Executive Officer, Veronique Andrieux, said foreign aid groups are working at breakneck pace to help Bangladesh cope with the mass influx. Clean water, food, shelters, hygiene and sanitation are the top priorities as refugees try to combat storms, she said, adding that stagnant water could become a major source for breeding diseases such as diarrhoea and cholera. Heavy rains have submerged several low-lying camps around the Kutupalong area of Cox's Bazar.

During a visit to the sprawling Kutapalong refugee camp in southeastern Bangladesh, close to the Myanmar border, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, said he was shocked by the "terrible violence" inflicted on Rohingya refugees fleeing Myanmar, and said their suffering would last far longer than the time it took to satisfy their basic needs.

"I was really struck by the fear that these people carry with themselves, what they have gone through and seen back in Myanmar," he told Reuters in the camp, where refugees live under thousands of tarpaulins covering the hills and rice paddies. "Parents killed, families divided, wounds inflicted, rapes perpetrated on women."

Nearly a quarter of a million Rohingya refugee children in Bangladesh are in an extremely vulnerable condition, many of them at the risk of malnutrition, global aid workers say. Organisations like Action Against Hunger have been working to provide aid to refugees in Kutupalong camp. Clean water, shelters, hygiene and sanitation are the top priorities for charity organisations as they prepare for the upcoming cyclones.

These half a million people are fleeing a Myanmar military offensive launched in response to about 30 coordinated attacks by Rohingya Muslim insurgents.

Myanmar is committing crimes against humanity in its campaign against Muslim insurgents in Rakhine state, Human Rights Watch said on Tuesday (26 August), calling for the UN Security Council to impose sanctions and an arms embargo. "The Burmese military is brutally expelling the Rohingya from northern Rakhine state," said James Ross, legal and policy director at HRW. "The massacres of villagers and mass arson driving people from their homes are all crimes against humanity."

The International Criminal Court defines crimes against humanity as acts including murder, torture, rape and deportation "when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack". HRW said its research, supported by satellite imagery, had found crimes of deportation, forced population transfers, murder and rape.

Doctors treating Rohingya Muslims who have fled to Bangladesh from Myanmar in recent weeks have seen dozens of women with injuries consistent with violent sexual attacks, UN clinicians and other health workers said. The medics' accounts lend weight to repeated allegations, ranging from molestation to gang rape, levelled by women from the stateless minority group against Myanmar's armed forces.

Addressing a gathering of world leaders at the United Nations, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari said: "The Myanmar crisis is very reminiscent of what happened in Bosnia in 1995 and in Rwanda in 1994." He added that the "horrendous suffering" had been caused by "state-backed programme of brutal depopulation of the Rohingya inhabited areas in Myanmar on the bases of ethnicity and religion."

A Myanmar government spokesman rejected the accusation of crimes against humanity, saying there was no evidence. Myanmar has also rejected UN accusations that its forces are engaged in a programme of ethnic cleansing.

Government spokesman Zaw Htay said no Myanmar government had ever been as committed to the promotion of rights as the current one. "Accusations without any strong evidence are dangerous," he told Reuters. "It makes it difficult for the government to handle things."

Myanmar, also known as Burma, says its forces are fighting terrorists responsible for attacking the police and the army, killing civilians and torching villages.

Myanmar's UN ambassador insisted there is no "ethnic cleansing" or genocide taking place against Muslims and objected "in the strongest terms" to countries that used those words to describe the situation in Rakhine State. Hau Do Suan used his "right of reply" at the end of the six-day gathering of world leaders at the General Assembly to respond to what he called "irresponsible remarks" and "unsubstantiated allegations" repeated by countries in their speeches to the 193-member world body.

"There is no ethnic cleansing. There is no genocide," he said. "The leaders of Myanmar, who have long been striving for freedom and human rights, will not espouse such policies. We will do everything to prevent ethnic cleansing and genocide."

He called the issue of Rakhine State "extremely complex" and urged UN member states and the international community "to see the situation in northern Rakhine objectively and in an unbiased manner." Pointing to the initial attack by the insurgent Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, known as ARSA, he said: "It is the responsibility of every government to fight against terrorism and protect innocent civilians."

The ambassador said there are several reasons for the exodus and "prominent among them is the fear factor." Following the attacks and the security operation, he said, "most of the women and children were forced to flee" while men were conscripted into ARSA to fight Myanmar's security forces. "The scorched earth policy employed by the terrorists is another factor," Suan said. "The terrorists planted IEDs everywhere, blew up bridges, and committed arsons."

Amnesty International has said it turned up evidence of an "orchestrated campaign of systematic burnings" by Myanmar security forces targeting dozens of Rohingya villages. The human rights group released video, satellite photos, witness accounts and other data that found over 80 sites were torched and said that fresh fires continued in Rakhine and that satellite and video images showed smoke rising from Muslim villages.

The Rohingya have faced persecution and discrimination in Buddhist-majority Myanmar for decades and are denied citizenship, even though they have lived there for generations. The government says there is no such ethnicity as Rohingya and argues they are Bengalis who illegally migrated to Myanmar from Bangladesh.

Myanmar has seen a surge of Buddhist nationalism in recent years, and the public is supportive of the campaign against the insurgents. Refugees arriving in Bangladesh have accused the army and Buddhist vigilantes of trying to drive Rohingya out of Buddhist-majority Myanmar.

How you can help the Rohingya refugees: Donate To Unicef UK , Oxfam, Action against Hunger, Amnesty International or UNHCR

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.