Yemen: Camping on the Edge of Catastrophe

IBTimes UK speaks to Habib Anam al-Ariki, co-founder of the Yemen Bright Future Organisation, about a nation gripped by fear, malnutrition and displacement.

After the mass uprising of 2011, Yemen narrowly avoided civil war when the discredited long-time president Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down. The road to stability, and prosperity, remains a distant dream.

IBTimes UK spoke to Habib Anam al-Ariki, the co-founder of the Yemen Bright Future Organisation (YBFO), who recently travelled with an Islamic Relief delegation to Yemen, where he witnessed a country - and a people - living on the edge of catastrophe.

Since mid-January 2012, 38,500 people have been displaced within the Hajjah governorate in northern Yemen, due to prolonged fighting between the al-Houthi group of Shia insurgents and their tribal rivals. This wave of ostracism has taken the official number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) across Yemen past 140,000, although the real figure is thought to be far higher.

At least 40,000 refugees are living in cramped conditions in tents, and enduring desert temparatures that soar to 46 degrees during the day. Al-Ariki is almost lost for words recalling the misery and suffering he encountered in these camps.

"It's very hard for the people who have been displaced. There is little access to medical assistance or care. When I think about the camps, one of the first cases that comes to mind is that of a lady I met who had learning difficulties. With nobody to look after her or check on her regularly she often ended up hurting herself. When I met her she was covered in blisters. She tried to boil water to make some tea, but somehow ended up throwing the water on herself."

Some refugees, whose plight predates the recent fighting, have been living in camps for three to four years, and with no schools on sites, the children's education is non-existent. The people managing the camps are now trying to recruit teachers from among the IDP communities, in a bid to set up classes for kids. There are also some vocational courses and schools for girls and women, so they can hone the skills which will provide better future prospects.

"Food is obviously also a problem. The camps I visited are managed by Islamic Relief and funded by the UNHCR, the World Food Programme, and other international originations such as Oxfam, but often the rations of food people are given are not sufficient," says al-Ariki.

Sana'a - Yemen's capital?

The human tragedy is everywhere in Yemen, according to al-Ariki. He had assumed conditions in the capital, Sana'a, would be less bleak; in fact, they were worse. Ragged orphans wander the streets and displaced families cling to life, tormented by poverty, illness and hunger. "I thought that people living in the capital would have better living conditions that those living in other governorates, but I was wrong. Some of the most shocking situations I witnessed during the trip were there," he says.

Recalling a visit to the suburbs of the capital, he remembers the case of a woman who was forced to live in a small room with her entire family.

"She has seven daughters and a son. Her husband had suffered a stroke and was admitted to hospital, but was later kicked out because he did not have the money to pay for his treatment. He died within three months of having the stroke. Her eldest daughter, who is 19 years old, also suffers from learning difficulties. She caught meningitis when she was a child but her family could not afford to treat her and that had devastating consequences on her health.

"The situation of the family is now precarious. They place they are living in was built by a wealthier man who needed people to guard his land. He made it clear to them; they will have to leave as soon as the land is sold."

Revolution; the price to pay

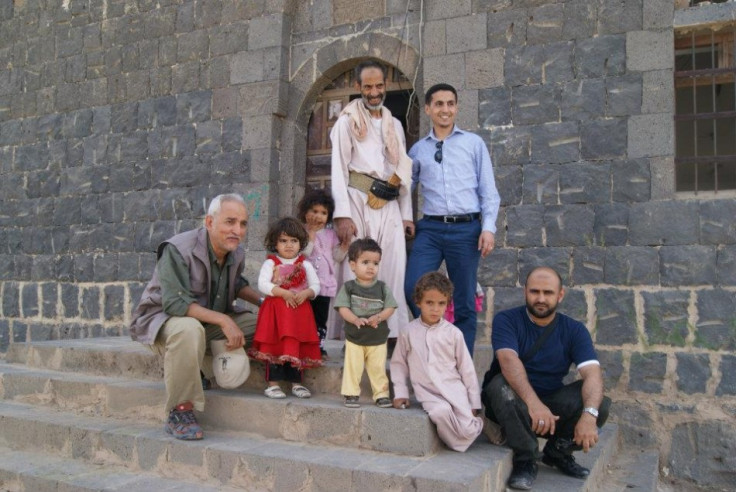

Al-Ariki also visited Arhab, a village near Sana'a, where he met Shaikh Almarani, leader of a local tribe and a supporter of the revolution that overthrew president Saleh last November.

His house was targeted by a special guards force in 2011 and he was forced to flee, along with his father and the rest of the family. They have just returned to the house, though it is still in a state of terrible disrepair and the family are now living in the only safe part of the family home - a corridor.

Much of the town has been torn apart by the war. Al-Ariki says: " Arhab is one of the saddest landscapes I have seen, I counted more than 50 houses which had been completely destroyed." However the new rulers of Yemen, led by the former vice-president Abd Rabbuh Mansur Al-Hadi, still suspect the community is bent on rebellion and shelling continues.

"One man we met had his house bombarded a day before we arrived", al-Ariki continues. "He had just finished building it and it took him several years. Now he has nowhere to go. I met another family who were living in a cave. They did not have any electricity and were forced to walk five to six miles to collect their ration of water."

Al-Qaida and Saleh

The militant Islamist group al-Qaida did not establish a formal region-wide foothold until January 2009, when al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula was formed through a merger of the movement's Saudi and Yemeni branches. However, the region has had a strong concentration of jihadists ever since the Saleh regime arranged for the repatriation of thousands of mujahideen in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The mujahideen returned to Yemen after fighting the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan, their number bloated by a number of non-Yemeni Arab war veterans, such as Osama bin Laden - who was adamant Yemen should play a central role in global jihad. Now the government is leading counter-insurgency efforts against al-Qaida, but once again the population is caught in the crossfire, as al-Ariki explains:

"The bulk of the fighting between the regime and al-Qaida insurgents is taking place in Abiyan province. Because of the fighting, more than 40 000 people fled Abiyan and headed to a nearby Aden. They had left everything behind and did not know where to go, so local NGOs placed them in schools. In addition to the terrible conditions they now have to live in, they also have to deal with the local population's resentment."

When asked about the locals' opinion on al-Qaida, al-Ariki says the people have mixed feelings.

"The people I spoke to had different opinions. Although some people saw the regime's counter-terrorism interventions as necessary, many of those who had left Abiyan told me they had been living with the insurgents for some time without clashing with them. They said they were chased out of their houses because of the regime's interventions."

Others blamed the rise of al-Qaida in Yemen on Saleh and his regime. Many saw the repatriation of the mujahedeen as part of a plan, he explained.

"A few people told me it was Saleh who first encouraged the al-Qaida insurgency by accepting the repatriation of the mujahedeen. In turn that helped him manipulate the international community into supporting him, and his regime, and providing funds."

After such an emotionally difficult trip, then, what did insights did al-Ariki bring back with him?

"I have a hard task ahead of me (with YBFO), but I remain determined to help the Yemenis. Half of the population is facing famine and malnutrition by the end of the year if nothing changes. My focus now is to tell and explain what I saw during my trip and appeal to people - whether individuals, small NGOs or big international organisations - to step up the action and help these people."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.