Misplaced Retribution: Capping Bankers' Bonuses [VIDEO]

Capping bankers' bonuses may seem like the ultimate retribution for the industry that has plunged and perpetuated the world into the worst financial crisis this century, but such a move is counterproductive as it will hurt flexibility, competitiveness and ultimately eradicate a key buffer for clawing back costs.

The European Union (EU) is already trying to thrash out a deal to cap the amount banks will be able to pay staff in bonuses in a bid to respond to anger from investors and the public over the role played by banks in the financial crisis.

The response has been mixed and while some countries, such as Germany, have already installed stricter pay policies on public and private banks, Britain has been the loudest voice in trying to find support in blocking such a new law.

'Bankers' bonuses' is of course an emotive subject, as Britain is still on the edge of falling into a triple dip recession and unemployment remains high compared to pre-crisis levels, so reading about bankers being paid thousands, if not millions, in addition to their base salary is particularly hard to stomach.

After the taxpayers bailed out RBS and Lloyds from collapsing, hearing that its chief executives, let alone thousands of employees, have a multi-million pound pool of cash waiting to be paid out is a particularly hard notion to bear.

But while on the surface, capping bonuses seems like a sure fire way to quash public anger while also providing less incentive for bankers to commit risky trading activities and mis-selling, it will in fact just place banks and the taxpayer in an incurable predicament should the firms need to claw back costs.

Benefits of Bonuses

Bonus structures are not as simple as the public perceives and work as a decent bufferzone for recouping costs should the bank run into trouble.

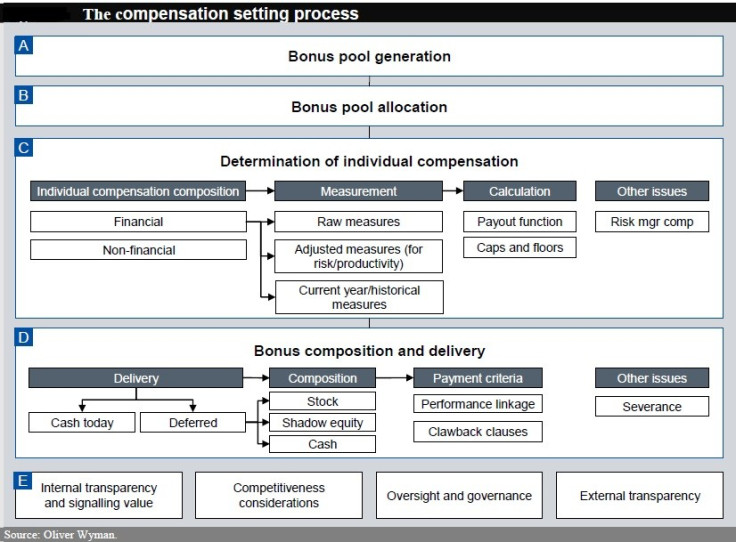

As detailed in figure 1 from an Institute of International Finance (IIF) report, the annual compensation setting process at major wholesale banks is a complex affair and typically involves at least three rounds of formal review and the involvement of many different functions.

Once a bank determines the overall bonus pool, it's then allocated between the divisions and business units, with a number of adjustments made, including 'reserving adjustments' whereby a percentage of the bonus pool is held in reserve in good years in order to subsidise bonus payments in years of weak performance, says the IIF report, which is one of the most comprehensive studies on bonus and compensation systems to date.

This has become particularly true over the past few years.

Comparing two UK banks, Barclays and RBS, both have had similar issues in terms of Libor fixing and mis-selling scandals, have settled with similar authorities and have paid huge fines in terms of their misdemeanours.

However, RBS is 83 percent owned by the taxpayer, while Barclays managed to avoid any state intervention when the financial crisis nearly led to the collapse of the banking system.

While Barclays and RBS both settled separately with authorities for millions in fines alone for Libor fixing charges, both used the same bonus clawback provision to pay for litigation costs and charges.

As detailed, in a series of Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS) hearings with Britain's biggest banks in order to determine what led to the spate of scandals that rocked the industry, bank executives were keen to point out that bonus systems are a very important element to providing flexibility and competitiveness for the industry as a whole.

In quick comparison, if no such a bonus pool existed, where would the payment of fines or compensation for other areas be derived from?

Certainly for RBS this would be a conundrum.

As with Barclays, the fact that its share price rose to a one year high, despite recording a plunge in profits, was indicative of its overall health because bonus clawbacks provided a decent buffer to pay back mis-selling compensation, Libor fixing charges and operational restructuring.

Fighting Fixed Pay

Essentially a cap to bankers' bonuses is already becoming counterproductive.

Ever since public outcry over bankers' pay packets seeped into lawmaker's agendas, banks have already put contingencies in place to boost fixed base salaries ahead of a possible cap.

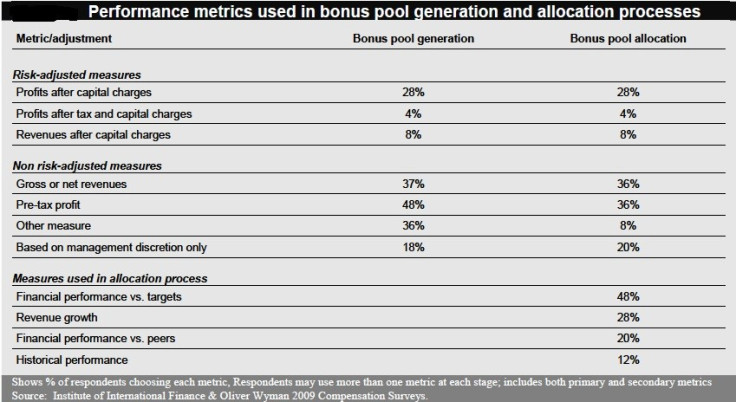

As bonuses are awarded on a risk adjusted basis, the final decision for award can be either deferred or clawbacked, as demonstrated in figure 2.

However, if bonuses substantially diminish but fixed base pay goes up, this means that in the event of banks needing to buoy up their balance sheets or pay for substantial fines, the mechanism of clawbacks cannot be implemented.

With fixed pay, the base salary cannot be clawed back, nor can it be deferred.

Furthermore, it will by capping bonuses fixed pay rates in the banking industry will continue to rise in order to compete with other global banks that will not have to adhere to such measures and retain the best talent in the industry.

The Mayor of London Boris Johnson has become the latest politician to voice his concerns over this issue when he spoke with the capital's free newspaper City AM.

He said that the UK doesn't need Europe "butting in on bonuses" a cap would lead to unintended consequences, such as pushing up salaries and making the sector less flexible, as well as making it harder for banks to cut costs in a downturn.

As IBTimes UK has detailed extensively the problems for all banks, and in particular RBS who has had to claw back costs, through bonuses is not over.

While, it is important to set a change in the banking industry overall, lawmakers have to tread carefully as they don't want to end up implementing changes that does the opposite of what they are intending.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.