Naloxone: Battling heroin and fentanyl deaths one shot at a time

IBTimes UK examines naloxone, a miraculous medicine that brings heroin overdosers back from the brink of death.

Claire* was making a cup of tea when her friend stopped talking and slipped into a heroin overdose. She ran from the kitchen into the sitting room, hauled him off the sofa and frantically tried to force air into his lungs.

But his lungs felt closed. His face went from grey to blue and his lips turned cold. Then came a gurgling death rattle.

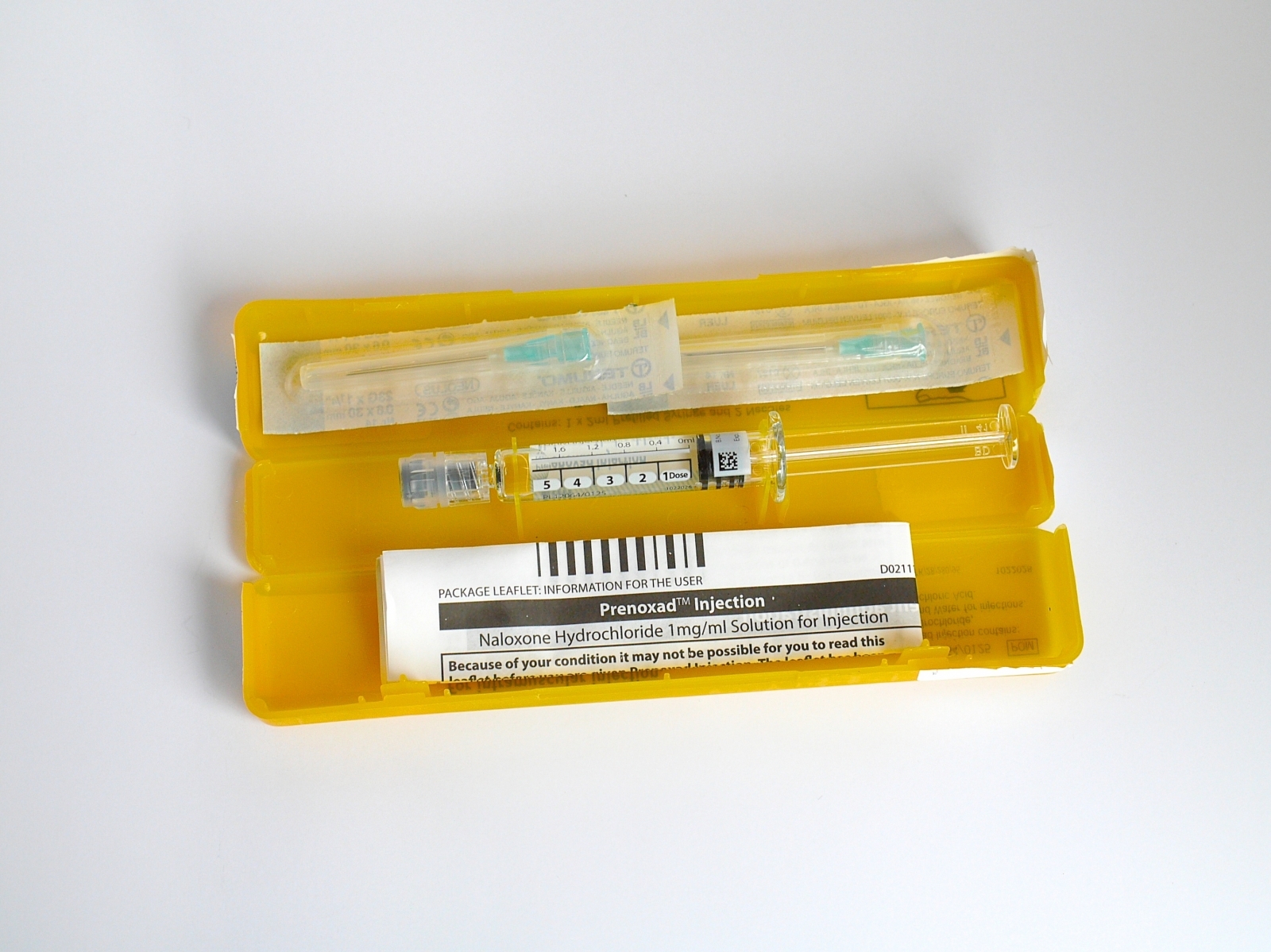

Stoned and terrified, Claire remembered the little yellow box in her drawer. She took out a pre-filled syringe and drove it through his jeans into his leg. A minute later he stirred. He was up and moving within half an hour.

There were 2,038 opiate-related deaths in England and Wales in 2016. There would have probably been 2,039 if Claire hadn't collected that yellow box – a Take-Home Naloxone kit – from her local drug treatment service.

Naloxone is a medicine that almost instantly reverses the effects of heroin overdoses. Paramedics have carried it for decades but now it is slowly making its way into the hands of drug users throughout England.

The opiate family, which includes heroin, morphine and fentanyl, are respiratory depressants – they stop the brain from telling the body to breathe. The more opiates in a person's system, the higher they get, and the more at risk their bodies are of shutting down.

"When somebody goes over, they don't feel like an alive person," says Claire, an energetic 48-year-old. "It was like he was ice inside."

Opiates are especially dangerous narcotics. They were responsible for 54% of all drug poisoning deaths in England and Wales in 2016, according to the ONS. But the distinct threat they pose to the respiratory system has a silver lining: there is an antidote.

<sub>*Name changed to protect identity.

What is naloxone?

First synthesised in 1961, naloxone stops opiates binding onto the brain, which is then able to remind the body to breathe again. It is harmless when given to a non-opiate user. Its most severe side-effect is the potential to cause extreme withdrawal symptoms in a high person.

"I was shocked by how quickly and how well it worked," says Martin McCusker, who, like Claire, used naloxone to bring a friend back from death's door. "I've seen a lot of overdoses but this was bad – the girl was barely breathing. I administered the naloxone and within a minute she was sitting there talking. It was amazing."

McCusker – a genial 50-year-old who recently swapped the cigarettes for a vape pen – is head of the Service User Council in Lambeth, south London, a forum that gives a voice to residents using the borough's methadone clinics and other drug treatments.

The Conservative/Lib Dem Health and Social Care Act of 2012 made councils in England responsible for their own drug and alcohol services. They commission competing providers, which treated almost 290,000 people with substance issues in 2015-16, according to Public Health England (PHE).

After a tour of the needle exchange, blood testing facilities and counselling spaces at Lorraine Hewitt House in Brixton, McCusker takes a yellow naloxone box from a pile, removes the syringe and quickly explains how to save someone's life.

He has given this training session countless times since October 2015, when Take-Home Naloxone legislation enabled drug services to hand out free kits – without prescription – to anyone at risk of overdosing or who might witness an overdose, like users' friends and families.

This second group is vital because opiate overdosers pass out – they do not know what has hit them, let alone have the strength to resuscitate themselves.

"You can have as much naloxone as you want," McCusker says. "But if you're by yourself you're f**ked."

Martindale Pharma sell the easy-to-use intramuscular injections, branded Prenoxad, to treatment providers for £18. In the US, naloxone is most commonly recognised as a nasal spray called Narcan made by ADAPT Pharma.

Some of the most at risk heroin users in England stay in homeless hostels. And 29% of people starting opiate treatments have no fixed abode or housing problems, according to PHE.

"That's where the deaths are happening," says McCusker, who recalls giving training sessions at a Lambeth hostel to "one guy in a wheelchair, another guy in an oxygen mask and another guy on the floor because his back was in bits."

St. Mungo's – a charity that puts a roof over 2,700 heads in the south of England every night – hosted naloxone pilot schemes prior to the 2015 law change. It found that clients were more likely to involve staff and emergency services in overdose situations when naloxone was available.

Head of the Complex Needs Team, Andy Mills, says the drug has helped move the sector away from the "very old days" of clients freaking out and "dumping bodies outside rooms because they thought they'd get evicted."

Mills and his deputy Rita Martins make sure St Mungo's hostels in London and beyond link up with local treatment services and get hold of naloxone wherever it is needed. They say that naloxone culture saves lives, empowers people to take better care of their general health and contributes to "recovery capital" – the resources a person needs to improve their life.

"People who are sometimes written off for not being the most together, smart individuals, actually respond in a very responsible fashion around an overdose scenario," says Mills.

Hostel workers have access to kits too because, like a user's friends and family, they may be on hand during an overdose. At St Mungo's staff and clients undertake training together, opening up "more conversations around risk and a more open relationship with clients," according to Martins.

Measuring the extent of naloxone provision in England is tricky. In Scotland, where drug treatment is nationally coordinated, more than 8,000 kits were issued in 2015/16. However, no comparable figure is available south of the border because councils commission their own drug services.

In July, the Local Government Association reported that 90% of local authorities in England had started distributing Take-Home Naloxone kits. The survey was anonymised but Liverpool is widely believed to be the only major urban area not yet doing so. The council says it will launch later this year.

Regardless, the LGA's figure of 90% is a red herring. The questionnaire informing the report did not ask authorities how many kits had been dished out, at how many services and, crucially, how intensively they were being promoted. Insiders describe the national picture as a "postcode lottery".

There is no data to back up this claim but the reaction of the paramedics arriving at Claire's flat in late 2016 may be illustrative: the medics were delighted and shocked to find her already treating her friend – it was a first for them, despite working in London where every borough is ostensibly signed up to the scheme.

"If you go to a local authority they'll say 'yes of course we do' but when you speak to people on the street – and I always ask them about naloxone – it's a very different message," says McCusker.

The situation in homeless hostels is even more opaque than at council level. There isn't even a national accommodation database, let alone information about what is in medicine cabinets.

Lambeth and St Mungo's have been at the vanguard of the Take-Home Naloxone movement, thanks to their association with South London and Maudsley NHS Trust, whose doctors helped pioneer it.

Chief among them is Professor John Strang. In a 1996 BMJ editorial he first argued that "home-based supplies of naloxone would save lives". Now, 21 years later, he says it is "pretty indefensible" that some healthcare providers are not pushing it towards people that need it.

The 2015 Take-Home Naloxone legislation coincided with average cuts of 14% to substance misuse budgets across England, according to the King's Fund, with more cuts following each year since. It is understandable that take-up has been sluggish.

But not defensible. A naloxone kit costs just £18 and lasts for a few years. "You look at the cost of other new medicines that come into the healthcare system," says Strang. "They're orders of magnitude greater – I think the issue is more of a moral one."

A typical, uninformed, objection to free naloxone is that the taxpayer shouldn't be burdened with treating people who persistently take harmful drugs. But Strang compares a habitual heroin user with a diabetic who, against his doctor's advice, continues to eat cream cakes. Should we take away his insulin?

Even if prejudice is allowed to cloud the issue, Take-Home Naloxone is likely to save the taxpayer money. A 2013 study from the US found that giving naloxone to a heroin user is cost effective up to $2,429 (£1,835) – 100 times the price of the little yellow boxes.

Strang, a veteran researcher and clinician, puts himself in the shoes of someone who has just lost a child to a heroin overdose. "You'd just think: 'Why have people not told me that I can have the antidote? Why on Earth would they not let me have that?'" he says, adding: "It's difficult to think of an answer."

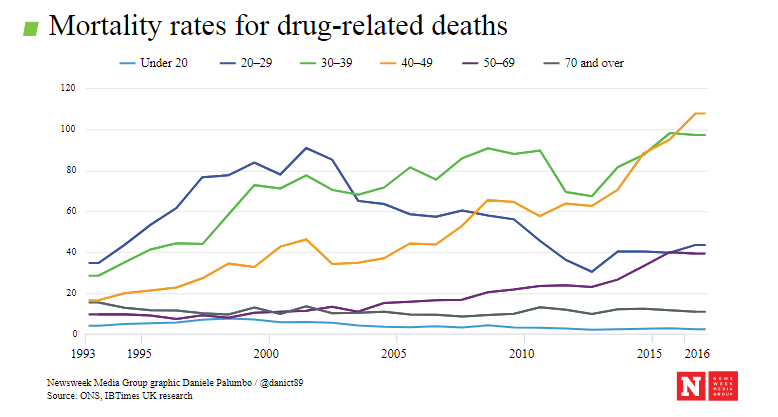

No one denies that progress – albeit slow – is being made. But heroin-related deaths in England are at an all-time high. The reasons for this are varied and complex but two stand out; user age and drug purity.

Heroin users are getting older. The number of under-25s entering drug treatment services with opiate problems has fallen by almost 80% in the last decade, according to PHE. An ageing cohort of heroin users – in many cases drinkers and smokers – are increasingly vulnerable to underlying health problems, which abet drug-related deaths.

Meanwhile, the strength of UK street heroin has more than doubled from an average of 18% purity during a 'drought' at the start of the decade to 44% in 2015, according to the National Crime Agency (NCA).

"People's use patterns unfortunately didn't shift quickly enough to match those increasing purities," says Dan Williams, a researcher at Release. "They got caught out and carried on using quantities that they were able to tolerate at low purity."

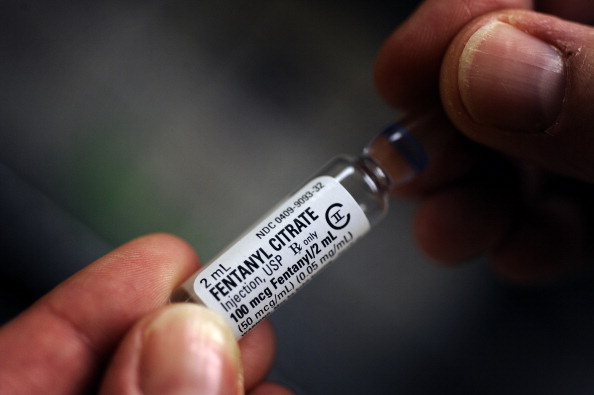

Added to this already dangerous mix is fentanyl: a synthetic opioid, 50-100 times stronger than heroin, ravaging communities in North America. Its cousin carfentanyl is 100 times stronger again.

On 1 August, the NCA held a briefing in London to announce that at least 60 UK drug deaths had been linked to fentanyl and its analogues in the previous eight months. The agency said it was "cautiously optimistic" that fentanyl-laced heroin would not flood the UK market, but McCusker said that users, ever in search of a stronger hit, were already starting to seek it out.

Several police forces in the US now routinely carry Narcan naloxone sprays after incidents where first responders accidentally ingested tiny amounts of fentanyl and collapsed. The sprays can also be used to revive members of the public.

"If there is any upside to fentanyl being available," says Williams, "it is that it's woken up law enforcement to the dangers and will hopefully make them more responsive in terms of countering it with things like naloxone."

At present, Metropolitan Police officers do not carry or administer naloxone. That policy could change quickly if one of their number goes down during a drugs raid. A spokesman for the Met said they might also revise their naloxone position "if a UK licensed non-needle option [e.g. a spray] becomes available".

The fact that the Met – a crime-fighting force – supports the wider provision of Take-Home Naloxone shows there is little debate at institutional levels about the merits of the initiative, which will continue to gather steam as opiate deaths remain high.

"When something like that happens in your house," says Claire, remembering the dread when her friend turned blue, "to have the ability to act at such a critical moment. Life and death. To do something that is going to save that person's life. There's no question."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.