Bhopal gas tragedy: 30 years on from the world's worst industrial disaster [photo report]

The world's worst ever industrial disaster took place 30 years ago. On the night of 2 December 1984, a pesticides factory accidentally released a cloud of cyanide gas into the air, killing thousands of people in Bhopal, India.

The government recorded 5,295 deaths, but activists claim 25,000 people died in the aftermath and following years.

Thirty years later, the toxic legacy of the Bhopal gas tragedy lives on as victims and their families are still struggling to cope with the after-effects of the disaster.

Human rights groups say thousands of tonnes of hazardous waste remains buried underground, slowly poisoning the drinking water of more than 50,000 people and affecting their health.

About 100,000 people who were exposed to the gas continue to suffer today with sicknesses such as cancer, blindness, respiratory problems, immune and neurological disorders. Some children born to survivors have mental or physical disabilities.

"There is a very high prevalence of anaemia, delayed menstruation in girls and painful skin conditions. But what is most pronounced is the number of children with birth defects," said activist Satinath Sarangi from the Bhopal Medical Appeal, which runs a clinic for gas victims. "Children are born with conditions such as twisted limbs, brain damage, musculoskeletal disorders ... this is what we see in every fourth or fifth household in these communities."

Sarangi admits there has been no long-term epidemiological research which conclusively proves that birth defects are directly related to the drinking of the contaminated water.

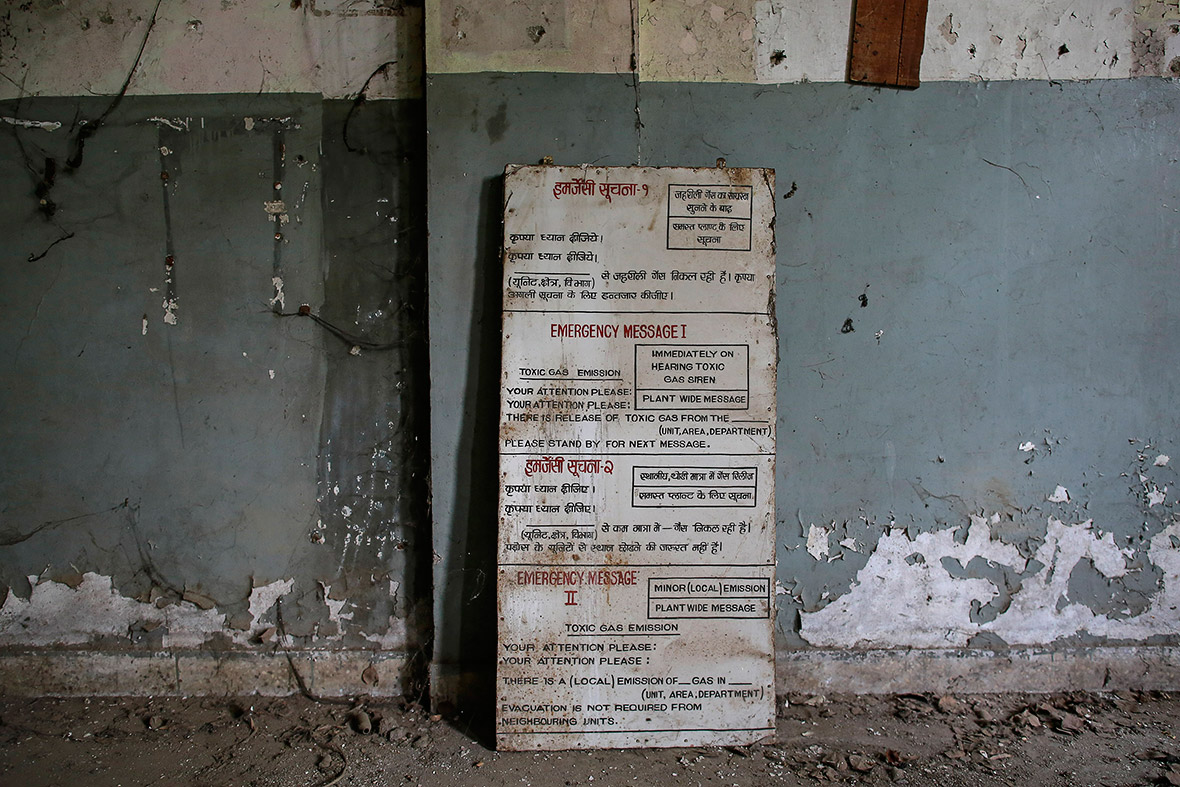

Beyond the iron gates of the derelict pesticide plant, administrative buildings lie in ruins, overgrown with vegetation. Massive vessels, connected by a multitude of corroded pipes, have rusted beyond repair.

In the dusty control room, a soiled sticker on a wall panel reads "Safety is everyone's business".

In a rehabilitation centre run by the charity Chingari Trust, located 500 metres from the factory site, disabled children gather for treatment which ranges from speech and hearing issues to physiotherapy.

While those directly affected receive free medical health care, activists say authorities have failed to support those sick from drinking the contaminated water and a second generation of children with birth defects.

The government was forced to recognise the water was contaminated in 2012 when the Supreme Court ordered that clean drinking water be supplied to some 22 communities living around the factory site.

"I don't think there is any doubt now that the waste dumped by Union Carbide is a serious problem and that it needs to be dealt with urgently," said Sunita Narain, director of the Delhi-based think-tank Centre for Science and Environment.

Studies by Narain's organisation in 2009 found samples taken from around the factory site contained chlorinated benzene compounds and organochlorine pesticides 561 times the national standard.

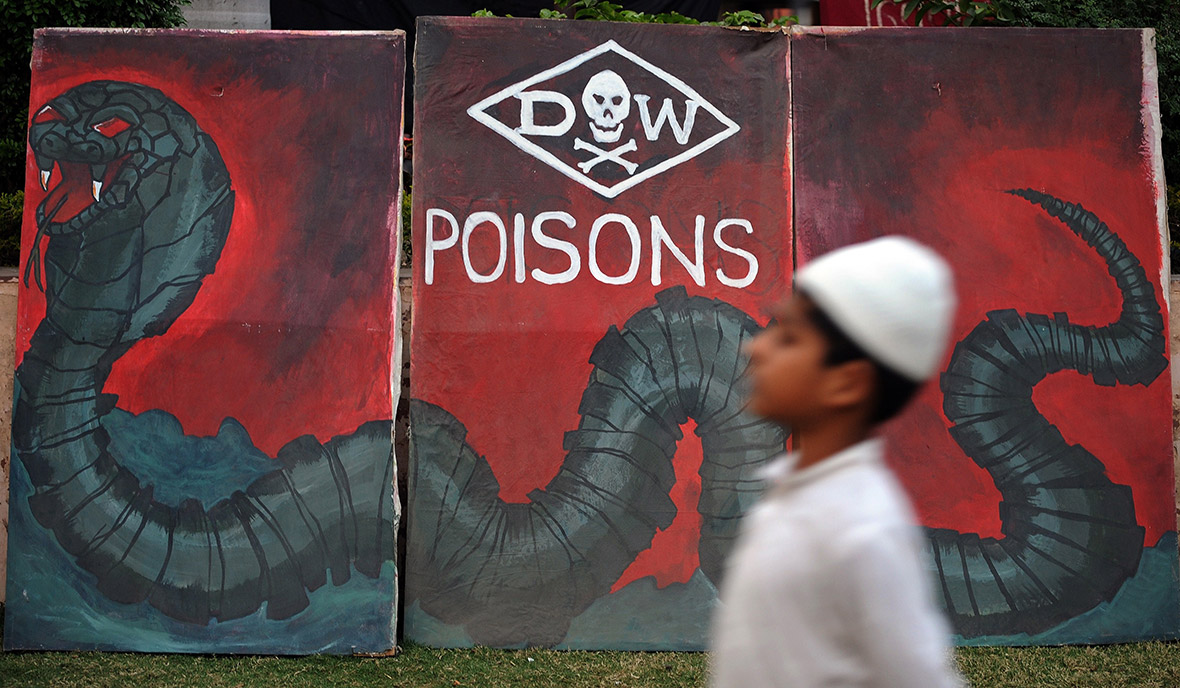

Dow Chemical acquired Union Carbide in 2001 but refuse to accept any responsibility for this waste, and the contamination. Union Carbide was sued by the Indian government after the disaster and agreed to pay an out-of-court settlement of $470m (£299m) in damages in 1989. The company says the Indian government then took control of the site in 1998, assuming all accountability, including clean-up activities.

"New victims of the Bhopal disaster are born every day, and suffer life-long from adverse health impacts," said Baskut Tuncak, UN special rapporteur on human rights and toxic waste.

"Without cleaning the contamination, the number of victims of the toxic legacy left by Union Carbide will continue to grow, and, together, India's financial liability to a rising number of victims," he added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.