Book Review: 'The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It' by Owen Jones

Power and mentality. These two attributes, rather than class and privilege, indicate whether you are in the establishment or not. That is, of course, if you agree with Owen Jones.

The socialist political commentator has switched his focus away from outlining the demonisation of the working-classes in his first book, Chavs, to unmasking and challenging Britain's elite in The Establishment.

Jones, an Oxford University graduate, who worked as a researcher for a Labour MP and now writes a weekly column in The Guardian, wastes no time in heading off an inevitable ad hominem attack.

"Some will claim that I am, myself, a member of the establishment. But it is not someone's background, or their education, or even whether they have a public platform or degree of influence that defines whether they are part of the establishment. It is about power and mentality."

The people exercising this power and 'we are talented enough to rule' mentality are called the "Outriders". This group, according to Jones, started a counter-revolution in 1947 against the pro-big state and anti-individual ideas of the day.

All revolutions need to have a figure head, and the Outriders had the economist Friedrich Hayek. But this revolution, if we take Jones' word for it, was more Menshevik than Bolshevik.

The group used thinktanks, like the Institute of Economic Affairs and the Centre for Policy Studies, to push their ideas. Caught unaware, the political class were usurped in a bloodless coup by the neo-liberals. The thinktanks enabled the Outriders to win the intellectual war.

These modern elites have infiltrated Britain's main institutions: the media, the police, and the political class. They are in charge. The result: Inequality, hypocrisy, the watering down of employment rights and the mass management of democracy. But how has this miserable state of affairs been established?

Jones argues that the Outriders have seized control by shifting the "Overton Window", the narrow view of policies that the public will accept, in their favour. The Outriders used the "mediaocracy" to do this.

The Mediaocracy

Journalists should attack the devil. That was the maxim William T Stead lived by and, through his actions, universalised. Stead, a pioneer of investigative journalism, exposed many of the injustices of the Victorian era.

Stead died on the Titanic, but he left a legacy of taking on the status quo. If Stead were to read Jones's take on modern journalism, he would be incensed.

Jones argues that the modern media focuses "their fire at the bottom of society". By doing so, journalists "deflect scrutiny from the wealth and powerful elite at the top".

"All of which is hardly a surprise, given that their owners are themselves part of that elite, ideologically committed to the status quo," Jones says.

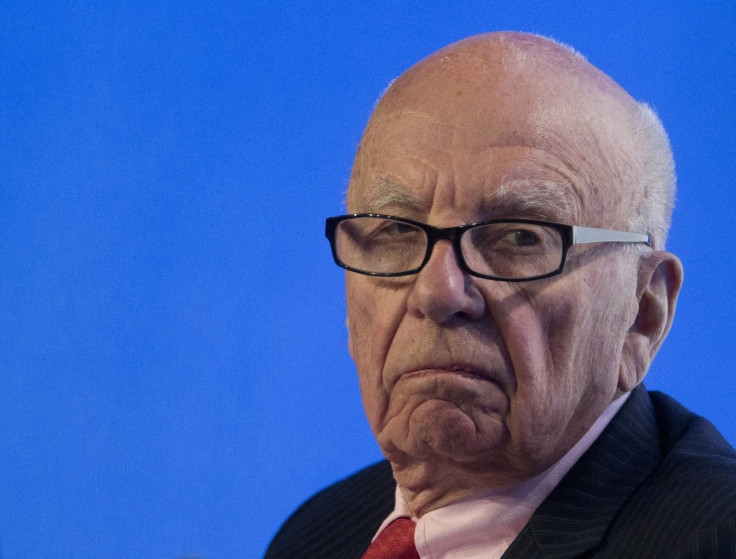

This means that politicians who do not toe the establishment line are dealt with. Jones explains his point by using Neil Kinnock's treatment by Fleet Street during his years as Labour Party leader and the Iraq War as case studies. In particular, he pays Rupert Murdoch close Attention.

The Australian media baron "helped catapult John Major into Number 10" and, after New Labour "no longer seemed to pose any threat", The Sun "dramatically swung behind" Tony Blair.

By 2003, "the media became a pillar of the spin effort in the march towards conflict". Insights on Murdoch's power on politics are offered from David Wooding, Damian McBride, Tom Watson MP, Christopher Hird and Chris Bryant MP.

Jones goes onto give a partisan and simplistic account of Murdoch's attack on the trade unions. He explains how, during the 1984/5 miners' strike, The Sun was going to print a picture of then National Union of Mineworkers leader Arthur Scargill raising his hand "in a manner that could be deviously twisted into a Nazi salute", with the headline 'MINE FUHRER'. Jones explains that the unionised printers at Wapping refused to publish the splash.

"Such power was intolerable to the Murdoch empire, and the print unions were crushed" Jones says. The villain here is clearly Murdoch, and the heroes the print-workers.

But Sir Harry Evans, the former editor The Sunday Times and the most qualified candidate to be named heir of Stead, has a different take on the print unions.

When his Insight team revealed that the drug Thalidomide caused birth defects and battled for the victims' families to receive compensation, Evans says the print unions attempted to "sabotage" the publication of the story. In other words, they stopped him attacking the devil.

"[The communist print union official Reg Brady], and his cohort of gangsters, said 'we're not printing the paper unless you pay us more money'," the former editor explains.

"They lost me half a million copies of that newspaper. Week after week, after week, we faced this."

For Evans, the son of a union supporting Mancunian railway driver, Murdoch was more hero than villain when it came to the unions. "The carnivore liberated the herbivores," he quips.

However, despite Jones's failure to give a full account of the complex print union dispute, he does rightfully point out the failures of modern journalism. Once a trade you could learn on the job, journalism now almost excludes those from modest backgrounds - like Evans.

The Social Mobility Commission, for example, found that more than half (54%) of the top 100 media professionals in the UK today are from private schools. The research also revealed that only 16% attended a comprehensive school. It is clear that the media has a class problem.

In particular, Jones identifies unpaid internships and costly post-graduate qualifications as barriers to the profession.

"Because the media disproportionately recruits from such a privileged layer of British society, there are inevitably consequences for how journalists look at news stories, or how they decide what issues are priorities," Jones says.

The best-selling author also highlights the revolving door issue, where journalists effortlessly switch from media to politics and vice versa. The Mayor of London and former editor of The Spectator, Boris Johnson, is the best known embodiment of this phenomenon.

Even the BBC is dubbed the "perfect vehicle for the Establishment" by Jones, since it allows "the free-market status quo to be portrayed as a neutral, a political stance". These factors, according to Jones, is how the establishment is "getting away with it".

The Con

The result is that the establishment has adopted an advertising riff, rather like the French football David Ginola used to say: "Because we're worth it".

They deserve the power. Not just in the media, but in politics, in finance and in the police. But what about those who aren't worth it? The people who are dependent on social security, on one form or another, are demonised. For Jones, this is thanks to the establishment's obsession with markets.

"The state is a bad thing, and gets in the way of entrepreneurial flair," Jones says. "Free markets are the real wealth creators. It is a sentiment echoed by elite politicians of all stripes."

This is a "con" for Jones. Big business is dependent on the state. Employers avoid paying fair wages because workers, through tax credits and other forms of welfare, are subsidised by the state.

The NHS, that great state-backed behemoth, keeps the workforce healthy. And infrastructure projects keep UK PLC up and running. In fact, for Jones, the state ends up providing a safety net for the rich.

Jones, by the time we get to his conclusion, has collated a one-stop shop for what is wrong with modern Britain. Considering he has analysed the media, politics, the police and the city, this is an achievement. However, his conclusion does not seem to follow from his premises.

Reform Not Revolution

Jones calls for a democrat revolution. He wants people to copy the methods of the establishment and use these against it. By using "savvy thinktanks", like Class and the New Economics Foundation, as well as building on protest movements like Occupy and UK Uncut, Jones argues that the Overton Window can be shifted to the left.

Democracy will be restored, politics will become more representative and the city will be tamed. But how will this happen? Jones wants businesses to be in public ownership and more like the employee owned John Lewis Partnership. He wants more devolution, a reformed European Union, a Royal Commission to investigate the police and link MPs' salaries to public sector workers' pay-packets, "forcing politicians to face some material consequences of their policies." Jones also wants a statutory Living Wage.

This is more reform than revolution; more Ferdinand Lassalle than Karl Marx. In fact, when it comes to radical, Jones dismisses Britain's most working-class party – Ukip. Nigel Farage's party represents the establishment in its purest form, according to Jones. "While ensuring that people's anger was directed at immigrants...Ukip supported policies that could only benefit the wealthy".

But the progressive left has tried to emulate Ukip's populism without its main policies, which is like having an amplifier-free rock band. The People's Party, Left Unity and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition are just some of the organisations that have popped up over recent years.

However, unlike Ukip, their impact has been very limited. The People's Party, which is supported by Jones, takes an anti-austerity stance. But its presence has not stopped The Chancellor's cuts programme. The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition, headed up by former Labour MP and staunch Trotskyist Dave Nellist, hardly made a splash at the local elections in May,

Jones foresaw this failure. He was sceptical of Nellist's goals when they sat across from each other on the Daily Politics.

"Why not put more pressure on the Labour Party in order to shift them toward a more progressive direction?" Jones asked. This is what he really wants – the Labour Party to be more like the Social Democratic Party of Germany. But after unmasking the horrors of the establishment, his readers will want a whole lot more.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.