Burns Night 2015: Scotland's paradoxical bard suits the complexity of devo max future

This time last year, people were wondering if it was to be the last time Scotland would celebrate Burns Night as part of the UK. Disappointment or relief at the outcome of the Scottish referendum is succeeded by its legacy, which now requires the sort of practical political expediency Robert Burns was versed in.

Scotland's governors are currently wrangling with Whitehall over exactly how devolved maximum devolution is; the SNP finds itself in a unique position to form alliances and cut deals looking ahead to the General Election; meanwhile, the bottom has fallen out of North Sea oil: the putative jewel in the nationalists' crown of self-governance. The complexity of Scotland's unfolding future is absolutely appropriate to its protean and paradoxical bard.

Considering how close Scotland came to breaking its 300 year union with England, it's worth reflecting on what it meant to people in Burns' day. In the immediate aftermath of the 1707 Union few Scots identified themselves as British. Yet within a century that was to change.

The end of feudalism opened the way for the development of full scale capitalism dependent on the British market. The creation of the Empire was a common enterprise, which Scots played an eager part in (by 1772 one out of every nine civil servants in the East India Company was a Scot). The Union was not the simple incorporation of Scotland into the English state, but the eventual construction of a new British state: the Empire was always the British Empire, never the English one.

For a nation traumatised by industrialisation, the rise of cities and mass emigration, Burns came to symbolise the vanished certainties of an increasingly mythologised rural past. This is the sentimental and apolitical vision of Burns. But the protean bard takes a number of forms.

Images of Burns are viewed through the optic of lieu de mémoire: a construction of national feeling, where lived events and the milieu of memory are replaced by a topology of symbolism, celebrated in museums, anniversaries, commemorations and poured over in written academic histories.

The political version of Burns is the radical supporter of the American and French Revolutions, whose poems and songs were sung by those fighting for democracy and social justice.

Burns was born in in 1759 in Alloway, just outside Ayr, the eldest son of seven children in a single-roomed cottage. By the age of 15 he was working as farm labourer. Like his father, Burns had a stab at being a tenant farmer but found it hard to make a living. Despite his poems being widely acclaimed, Burns failed to find a wealthy patron. Eventually in 1789, he moved to Dumfries and took a job as an excise man (a customs officer), which he held until his death in 1796.

Burns' radicalism is constructed around the most significant event in his lifetime, which was the French Revolution. Another major influence on his literature is said to be Tom Paine's "The Rights of Man". Burn tackled these ideas obliquely; we must remember that paranoia about the French Revolution and the mass distribution of Paine's ideas meant Britain had become a virtual police state.

In 1793, in Dumfries, Burns was effectively on trial because a government spy had told his employer, Her Majesty's Custom and Excise, that he was head of a group of Jacobin sympathisers. The Jacobin Club (Club des Jacobins) was the most famous and influential political club in the development of the French Revolution. Burns denied all the charges.

Privately and anonymously, he continued to write poetry for the movement. "A Man's A Man for A' That" was written two years after this vow of silence. Meanwhile, Burns was expedient in his display of loyalty to his employers. In 1795 he signed a petition to set up the Dumfries Volunteers to resist a French invasion and then wrote them an anti-French anthem.

He also took chances, however. The anonymous publication in 1793 of "Scots Wha Hae" coincided with trial of the most prominent Scottish champion of the French Revolution Thomas Muire. The song went on to become a contender for Scotland's national anthem.

The song is rousing battle speech before the fabled Scottish victory over the English in 1314 at Bannock Burn. The deployment of Scotland's heroes of the past, Wallace and Bruce provide a guise for Burns to invoke equality, liberty and fraternity – with a degree of impunity. It talks of fighting despots and tyrants in the name of liberty and stating that losing will mean "chains and slaverie".

Wha will be a traitor-knave?

Wha can fill a cowards' grave?

Wha sae base as be a Slave?

—Let him turn and flie.—

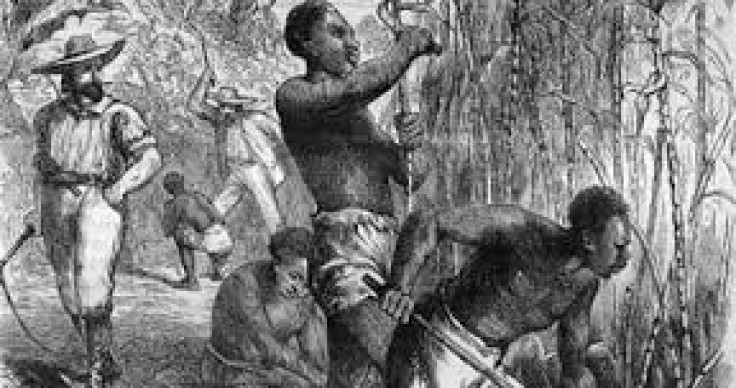

But the mention of slavery here, and in other poems by Burn is very problematic. One aspect of Burns' life that is deeply uncomfortable to modern Scotland concerns his plan to work on a plantation in Jamaica.

It is now widely known that Scotland's national bard was preparing to travel to Jamaica in 1786 to work as what he calls a "negro driver" on a slave plantation. He hoped to escape the hardships of the life of a tenant farmer as well as the irate father of pregnant Jean Armour.

The publication of Burns' first collection of "Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect" (1786), known as the "Kilmarnock edition" was intended to raise funds for the voyage; Burns reports that his very first purchase was the nine guinea fare across the Atlantic.

"The voyage was postponed however and the success of 'Kilmarnock' meant the plough driver was able to avoid the post of 'negro driver' by pursuing instead literary fame as a "quill driver" in Enlightenment Edinburgh," states historian Michael Morris.

The paradox here relates to the complex relationship between slavery, freedom and abolition – the latter is conspicuously absent from the works of the author of "A Man's A Man for A' That". This didn't stop Burns becoming an emblem of "mutual sympathy" for contemporary abolitionist poets, however.

The truth about Burns is that he cannot be reduced to an emblem of social justice, or some lost rural Eden, or a radical supporter of the French Revolution or anything else. But this is not to say his politics were muddled and inconsistent: from a diagnosis of political confusion it's a short step to the trite proposition that Burns is all things to all men.

We should remember that he was writing poetry and not political philosophy and as such was not aiming for strict consistency or logical coherence. He could oppose monarchical absolutism, while still cherishing the House of Stuart as a symbol of national pride.

And while most commentators hold the French Revolution to be the alpha and omega of Burns' political consciousness, historians like Liam McIlvanny have sought to show that many of the poet's political works were written three years or more before the fall of the Bastille.

In fact key research on popular radicalism has focused on how radical politics were informed by subtler factors such as dissenting Scottish Presbyterianism: the New Light with its subjugation of all forms of authority to the tribunal of individual reason.

In this analysis Burns' political writing becomes more complex and sophisticated than just the venting of lower class spleen, or espousing fashionable French extremism.

Even his subversive erotic poems have been described as "political bawdry". As Burns' famous biographer Thomas Crawford wrote "Almost everything Burns wrote was political in the broadest sense."

All this might seem rather remote from today's Scotland, devolution and the likes of the West Lothian question. But I can remember the first outing of a Scottish Parliament in 300 years, back in Edinburgh in 1999, which seemed like an important non-event, until some lady folk singer stepped up to perform Burns.

Watching the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and the Prince of Wales listen in respectful silence to her rendition of "A Man's A Man for A' That", was the first time I really felt the power of Burns' verse:

The honest man, tho' e'er sae poor,

Is king o' men for a' that.

Further reading:

Robert Burns: Recovering Scotland's Memory of the Black Atlantic, Michael Morris (2013)

A People's History of Scotland, Chris Bambery (2014)

Burns the Radical, Liam McIlvanney (2002)

Burns: A study of the Poems and Songs, Thomas Crawford (1960)

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.