Cambridge Spy Ring: What sensational MI5 files tell us about Soviet traitors Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean

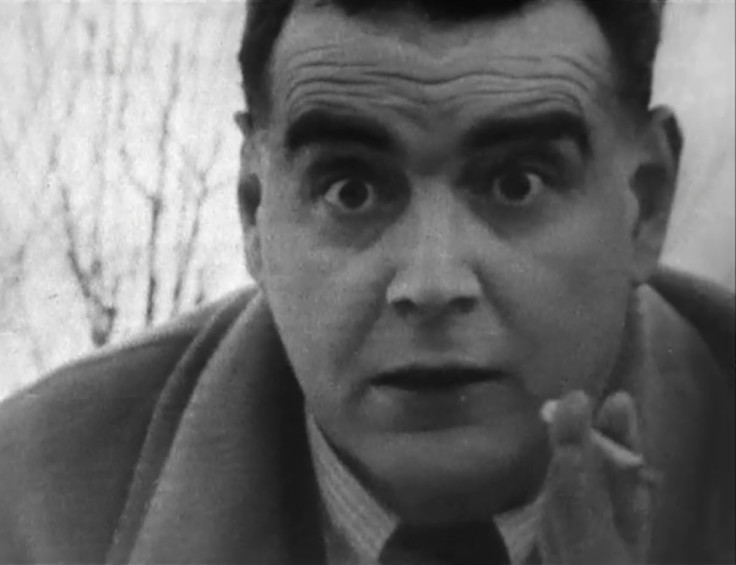

"Yard Hunts Two Britons" screamed the Daily Express headline on 7 June 1951 reporting the disappearance of British diplomats Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean. The disappearance was a godsend to the press, with the Daily Express immediately offering a £1,000 reward for information, which shortly afterwards was raised by the Daily Mail to £10,000.

Burgess's brother was offered £500 to collaborate with a water diviner and his boyfriend was sent around their old Paris haunts in the hope of finding the missing diplomat. By 1962, the Express had spent almost £100,000 on the story.

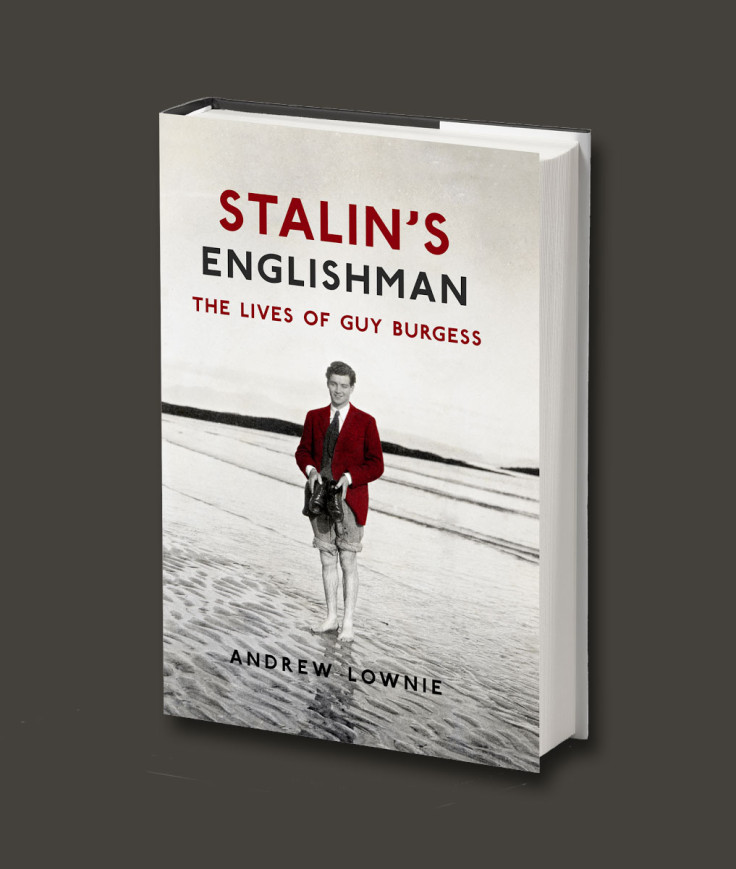

It's a story that has not gone away over the past 60 years, with each year bringing fresh revelations and renewed media interest. The internet has 17,700,00 references to Burgess and my recent biography of him, Stalin's Englishman, had a record five day serial in The Daily Mail.

Why the interest? It's a psychological detective story. Why should clever men at the very heart of the Establishment, who enjoyed its trappings, seek to betray it? Why did they devote their lives to a known totalitarian regime, abandoning friends and family, ending their lives in lonely exile in Moscow? How did they get away with it given their drunkenness, drug-taking and sexual promiscuity? Are there other spies still to be uncovered?

The release of over 400 files by the Foreign Office, Cabinet Office – from archives, hitherto unknown, at Hanslope Park in Buckinghamshire – and MI5 goes some way to answering some of those questions. It shows how extensive the inquiries were, which were conducted into the activities and disappearance of the two men and the new security measures implemented for government officials. It is a veritable Aladdin's Cave for the intelligence historian.

There are also revelations on right-wing extremists, other suspected Communist agents such as Harry Smollett – an agent run by Burgess – and Leo Long another member of the Cambridge Ring. Other releases include the inquiry into the disappearance of the MI6 agent Buster Crabb and personal files of the arms dealer Sir Basil Zaharoff and Lord Boothby, but the focus of the release is on Burgess and Maclean.

Missing gaps

We can now fill in some of the missing gaps in their careers, including what Burgess was doing in MI6's Section D and why he was dismissed – a driving offence. An analysis of the stamps in his passport suggest his travels to the continent on MI6 business in the late 1930s were more extensive than realised.

It also confirms that, according to historian Steven Runciman, Maclean and Burgess had "a roaring affair" at Cambridge. We also have a much clearer idea of what Burgess and Maclean did in the week they left, including the fact they lunched on each of the three days prior to their flight.

The released files include the transcriptions of the telephone intercepts placed on the various individuals involved in the drama, including Burgess's mother, after their disappearance. All the correspondence to and from Burgess in Moscow was opened and copied, giving a fascinating insight not just into his life there – he fell in love with a priest at a nearby monastery –but also, particularly through the correspondence with his mother, about his circle of friends and life.

New light is shed on the visit of Michael Redgrave and Coral Browne, the subject of Alan Bennett's play An Englishman Abroad, and it is revealed that Burgess had several approaches from literary agents to write his autobiography and there was an approach in 1955 for a film on the story called The Traitors.

It proves the close friendship he had with Sir Winston Churchill's niece and Sir Anthony Eden's future wife Clarissa – something she has always played down. He writes to his mother "Talking of girlfriends, I wonder what would happen if I sent my congratulations to Clarissa on her marriage to Sir Anthony Eden?" It confirms too that Burgess was engaged to Kim Philby's secretary in MI6 – and also his lover – Esther Whitfield and that Esther remained close not just to her former finance but also his mother.

Another revelation is Burgess had a dog called Joe, named after Stalin, and how annoyed he was to lose his dacha under government cuts when Maclean, whom he described as a "traitor", was allowed to retain both his Moscow flat and dacha.

Burgess's personal file at the Foreign Office has now been opened showing how close he came to being sacked several times from the Foreign Office – not for spying but poor work and indiscretion – and how his friends proved stronger than his enemies. Several times he was vetted for government work – in 1939, when he joined MI6, and in 1946, when he went to work for the Minister of State at the Foreign Office – but on both occasions he received good references and nothing was recorded against him.

The Cambridge University Socialist Society minute book for the early 1930s, removed by MI5 in the course of its investigations, shows all the usual suspects were members, including Philby, Maclean and Burgess, but also undergraduates who were later to renounce their youthful Communism and become pillars of the Establishment.

Kim Philby

It shows how Anthony Blunt put himself at the centre of the investigations offering help to both the authorities and the families thereby ensuring he knew exactly what was happening. Philby's interviews with MI5 reveal how he tried to deflect suspicion from himself on to his former friends, Burgess and Maclean, now safely in Moscow, and how many of the two men's close friends were evasive when questioned.

The files demonstrate that Philby was immediately suspected in 1951 but, without a confession, legal action couldn't be brought. Blunt and Cairncross, whose treachery was only separately revealed in 1979 with the publication of Andrew Boyle's The Climate Of Treason and a Sunday Times article, were also fingered quickly by MI5. Blunt was still being bugged in 1956 in an attempt to gather incriminating evidence.

It was known that the British authorities knew they could not prevent Burgess returning to Britain and no case would stand up in court but now we have all the agonising correspondence from 1958 to 1963 with the law officers advising on possible courses of action and Blunt being used to dissuade Burgess from returning and embarrassing his friends with all the attendant publicity. There were even concerns that Burgess and his mother might meet on neutral territory such as Switzerland and in one letter, he suggested to his mother she bring Philby on a visit to Moscow.

Perhaps the last word should be left to Burgess writing to his mother: "When the whole story is told, I don't think I shall come out of it too badly." We now have all the material to make up our own minds.

Andrew Lownie is a writer, journalist and historian who set up the Andrew Lownie Literary Agency in 1988. His latest book, Stalin's Englishman, is a biography of Guy Burgess and is out now.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.