Can Face ID offer users Fifth Amendment protection like passwords do?

It is still not clear if face recognition technology can protect users from self incrimination.

With major phone makers Samsung and Apple bringing face recognition to mainstream markets, it might have become easier for people to lock and unlock their phones, but questions of safety and security abound.

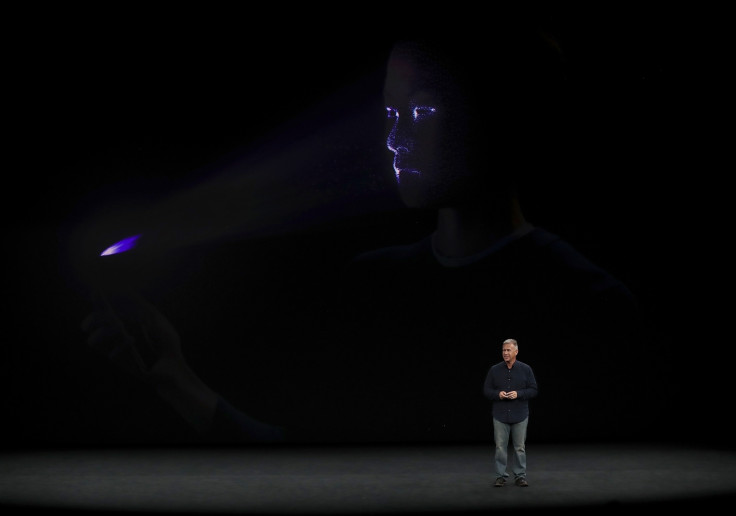

During the launch of the device on 12 September, Apple vice president Phil Schiller said that facial recognition, "is the future of how we'll unlock our smartphones and protect our sensitive information".

However, people don't seem to have much clarity on legal aspects concerning facial scanning and other biometric locking of gadgets.

Will facial recognition, iris scanning, and even fingerprints actually protect a person from forced self- incrimination as outlined in the Fifth Amendment if their phones get seized after arrest and police demand they open their devices?

A report from ARS Technica questions how this tech would work in scenarios that include law enforcement holding a phone in front of a person's face to unlock it and gain information from it.

The report pointed out that in 2014, the US Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement will require a warrant to search through people's phones after an arrest. A passage from the ruling on the case reads, "The Court's holding is not that the information on a cell phone is immune from search; it is that a warrant is generally required before a search."

A new security feature in iOS makes it possible for users to use a secret "cop button" to disable Touch ID in a hurry, making it impossible to get into the phone without manually inputting a passcode or PIN.

It is highly likely that this feature will be carried over to phones with face id in the future as well, points out the Verge. The report says that passcodes are protected under the Fifth Amendment as they are considered to be testimonial evidence — answering questions based on thoughts, which carry inherent Fifth Amendment protection — but biometrics are often taken as physical evidence.

The report likened it to a police officer demanding the combination to a lock from a suspect as opposed to seizing a physical key to open the said lock. Facial recognition is not yet tested in this context, but it is unlikely that it will be treated any differently from the way fingerprints are treated, says the report.

Jeffrey Welty, a law and government professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, in an interview with the Verge said, "Standing there while a law enforcement officer holds a phone up to your face or your eye is not a 'testimonial' act, because it doesn't require the suspect to provide any information that is inside his or her mind."

An argument was made against treating fingerprints as physical evidence earlier this year. In a Minnesota Court of Appeals a defendant argued that by revealing which finger he used to unlock his phone, he was in fact incriminating himself, based on knowledge that was inside his mind, and therefore should be considered testimonial evidence. This line of reasoning was, however, shut down by the court, the Washington Post reported.

"Bottom line, if you are concerned about whether law enforcement can compel access to your device, a password or passcode is much better than Touch ID or facial recognition, but it isn't ironclad," says Welty.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.