Central African Republic: How WHO is Aiding Victims of Extreme Conflict

If you want to see the true scale of the tragedy engulfing the Central African Republic, and the heroism blossoming in its midst, you need only visit Bouar, a small market town in the west of the country.

When violence broke out next to Bouar's hospital, Dr Wilfried Komoyo and his staff refused to stop working. They bravely battled on - an act of altruistic resilience made even more remarkable by the fact that several members of Komoyo's team had gone months without pay.

Such acts of selflessness are legion across the CAR. But the country should not be relying on incredible individual acts to ensure seriously ill people have a fair chance of life.

Events over the past few months have brought the deteriorating health system to the brink of collapse, as bloody clashes between rival sectarian militias continue, prompting UN chief Ban Ki-moon to warned of "ethno-religious cleansing".

Lynchings, rape and beheadings going unpunished, while the conflict has led to structural damage and widespread looting of medical equipment, which have made it next to impossible to provide relief to those who have been displaced.

But now help is at hand. The World Health Organisation, the Ministry of Health and humanitarian partners are working around the clock to strengthen health services, from immunisations to trauma care.

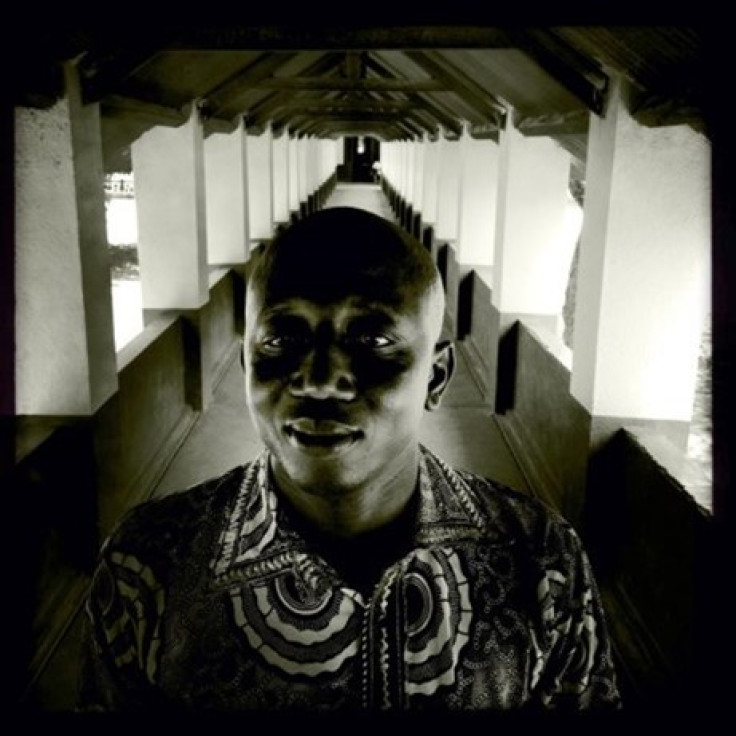

Dr Michel Yao, the WHO's senior health security adviser for humanitarian crises, explained the gravity of the situation – and what is being done to address the problem.

"The situation is extremely difficult, because at the time I was there, there was a lot of violence that was causing death," he told IBTimes UK.

Yao added that health workers were having to leave the facilities for safer grounds.

"They were fleeing to save their lives, so we did not have health workers and we did not have supplies to provide basic health services."

In early December, CAR exploded into violence amid mounting resentment towards a Muslim-led government. Muslim rebels seized power in March 2013 by overthrowing President Francois Bozize, who had been in power for a decade. His replacement, President Michel Djotodia, was accused of failing to prevent his forces from raping, torturing and killing civilians – particularly among the country's Christian majority.

When Djotodia's government fell in January, Christian vigilante groups began targeting Muslim civilians in retaliation. Thousands have been killed and displaced from their homes and this week, 30 more deaths were reported as a result of clashes between the predominantly Christian anti-Balaka and Muslim-majority Seleka rebels. To date, UN statistics show that 1.3 million people – a quarter of the population – are in need of aid.

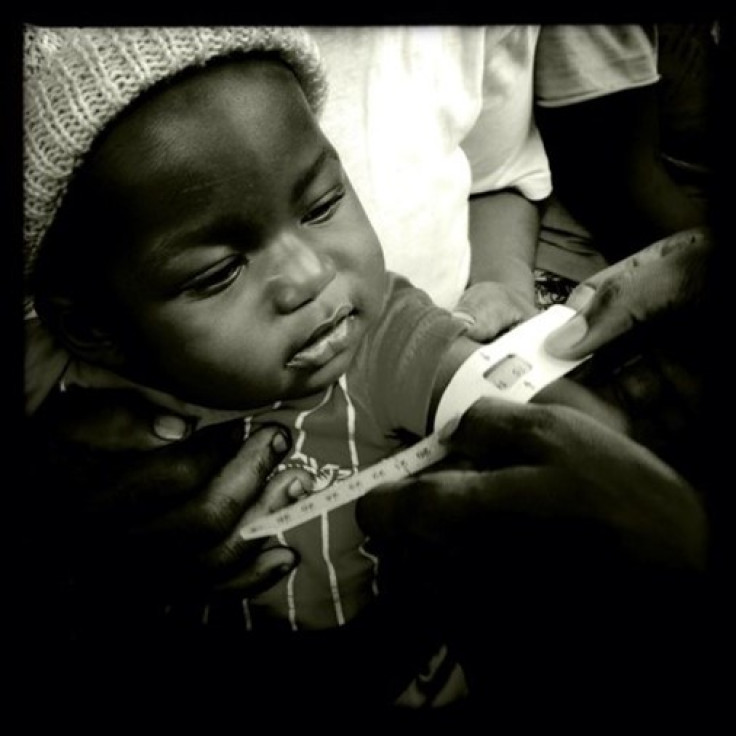

Although the situation is dire, the WHO and their humanitarian partners, such as the Red Cross, Medicine Without Borders and Save the Children, are still providing essential care. The three main services provided, Michel explains, are trauma care to those who have been injured in conflict, disease control and preventative measures, including basic services such as vaccinations.

Yao explained that the WHO and their partners work together to provide as much care as possible.

"We give care for injuries related to violence, as well as diseases such as malaria. The immunisations are mainly for children under 5 years old – in general, most consultations were for people with malaria. Our statistics show that 37% of people seeking healthcare were doing it for malaria."

Yet one of the major problems holding back such treatments is funding. Alongside the violence, Yao told IBTimes UK that a remaining challenge is the huge amount of funding necessary to improve basic healthcare.

"So far, the health partners are quite underfunded. In January, we were only funded by about 20%" he said.

"The lack of economic resources necessary to scale up interventions through mobile clinics is a significant problem. There is a very high risk of looting, and equipment is not insured. These are the challenges we are trying to address."

Progress is being made, however, and Yao hopes the deployment of peacekeepers will address the issue of security of medical staff in CAR.

"It is great news," he said. "We need more security to help us reach more people who are in need. The violence made it difficult to access to proper food, water or shelter, as well as to facilitate the return of health workers. They cannot work if they are their security is not ensured."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.