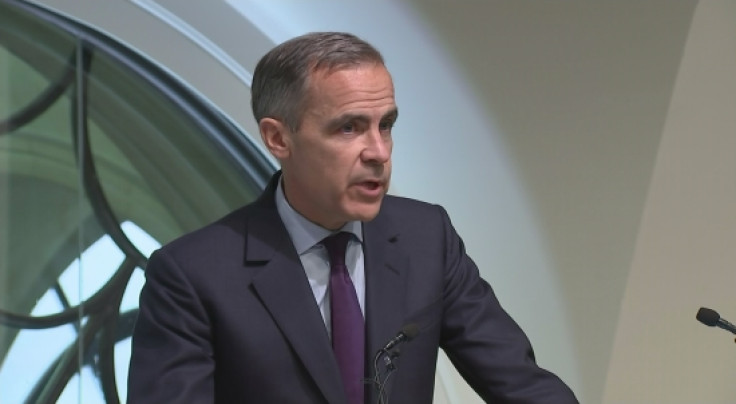

City of London can't be cut off from Europe because of Brexit, warns Mark Carney

Bank of England governor urges Britain to take 'the high road' in Brexit negotiations.

The City of London must not be cut off from the rest of Europe because of Brexit, the Bank of England Governor Mark Carney said on Friday (6 April).

Speaking at Thomson Reuters in London's Canary Wharf, Carney urged Britain to "take the high road" in the upcoming negotiations with the European Union, pleading politicians to steer clear of protectionism and to retain an open financial system.

"We are at a fork in the road," he said. "One path builds on the foundations of a new responsible global financial system that are being put in place [...] The high road leads to more jobs, higher sustainable growth, and better risk management across the G20.

"But there is another path – the low road – where trust and cooperation diminish, fragmentation hardens, capital flows are disrupted, and trade and innovation are curtailed."

In his speech, Carney reiterated an earlier claim that "London is Europe's investment banker" and that Britain was relied upon as a "pillar of strength for the international monetary and financial system".

"A decade of hard fought financial reform creates enormous opportunities," Carney said. "It is all too easy to give into protectionism, but the road less taken is often the most rewarding."

The BoE Governor also added firms with operations in Britain and in the EU should put contingency plans in place ahead of the upcoming negotiations and set them a deadline of 14 July.

Last week, in her letter to the EU which triggered Article 50 to formally begin the process to take Britain out of the 28-country bloc, Prime Minister Theresa May confirmed the UK would "not seek membership of the single market" when negotiations begin.

Leaving the single market will mean lenders will not retain access to the European banking passport system, which allows banks and other financial institutions authorised to operate in an EU country, or a state member of the European Economic Area (EEA), to conduct business across the union.

Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Luxembourg and Dublin have all emerged as possible destinations for London-based banks to relocate but analysts have warned it would be nigh on impossible to replicate London's environment abroad, in terms of workforce and infrastructure.

The former has a world-class transport network while its airport is a global aviation hub which serves a super-connector terminal for flights between the Americas and Asia. However, Germany's finance hub is not geared up to cope with a mass influx of bankers looking to escape a Brexit-burdened London.

Dublin faces a similar dilemma. Language, time zone and common law are the same over the Liffey as they are in London, while Ireland's 12.5% corporate tax rate has also proved very appealing with international firms.

However, while the advantages might be obvious, Dublin also shares some very familiar problems with London, such as a chronic housing shortage.

Last month, US investment banking giants Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley said they will relocate hundreds of jobs away from London before Britain and the European Union agree on any Brexit deal.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.