Drought forces a family in Somalia to sell teenage daughter into marriage: Heartbreaking photo report

Family forced into impossible situations as an an arc of hunger and violence stretches across Africa into the Middle East.

Drought and famine across the Horn of Africa are forcing families to make impossible choices. As the village wells dried up and her livestock died in the scorched scrubland of southern Somalia, Abdir Hussein had one last chance to save her family from starvation: the beauty of her 14-year-old daughter, Zeinab.

Reuters journalist Katharine Houreld and photojournalist Zohra Bensemra visited Zeinab and her family. IBTimes UK shares their harrowing story.

An older man offered $1,000 for her dowry, enough to take her extended family to Dollow, a town on the Ethiopian border where international aid agencies are handing out food and water to families fleeing a devastating drought.

Zeinab refused. "I would rather die. It is better that I run into the bush and be eaten by lions," she said. "Then we will stay and starve to death and the animals will eat all of our bones," her mother shot back.

The family had previously owned cows and goats and three donkeys that they hired out with carts for transport. But the animals died around them and Zeinab became their only hope of escape. For a month, she refused to agree to marriage, withdrawing into herself and running away when they forgot to lock her in her room. Finally, faced with her family's overwhelming need, Zeinab relented.

"We didn't want to force her," her mother said wearily, worry lines etched into her forehead as her daughter sat stony-faced beside her. "I could not sleep for stress. My eyes were so tired I could not thread a needle."

The dowry was received, the marriage celebrated, and union consummated. Zeinab stayed three days and ran away. When her family hired cars to drive them the 40km to Dollow, Zeinab went with them. Her husband followed. "He said, if the girl refuses me I must get my money back. Or I will take her by force," Zeinab said, quietly. "He sends me messages saying give me the money or I will be with you as your husband."

Her family could not repay even a fraction of the dowry. Their only assets are their two stained foam mattresses, three cooking pots and the orange tarpaulin that covers their makeshift dome. There is nothing else to sell.

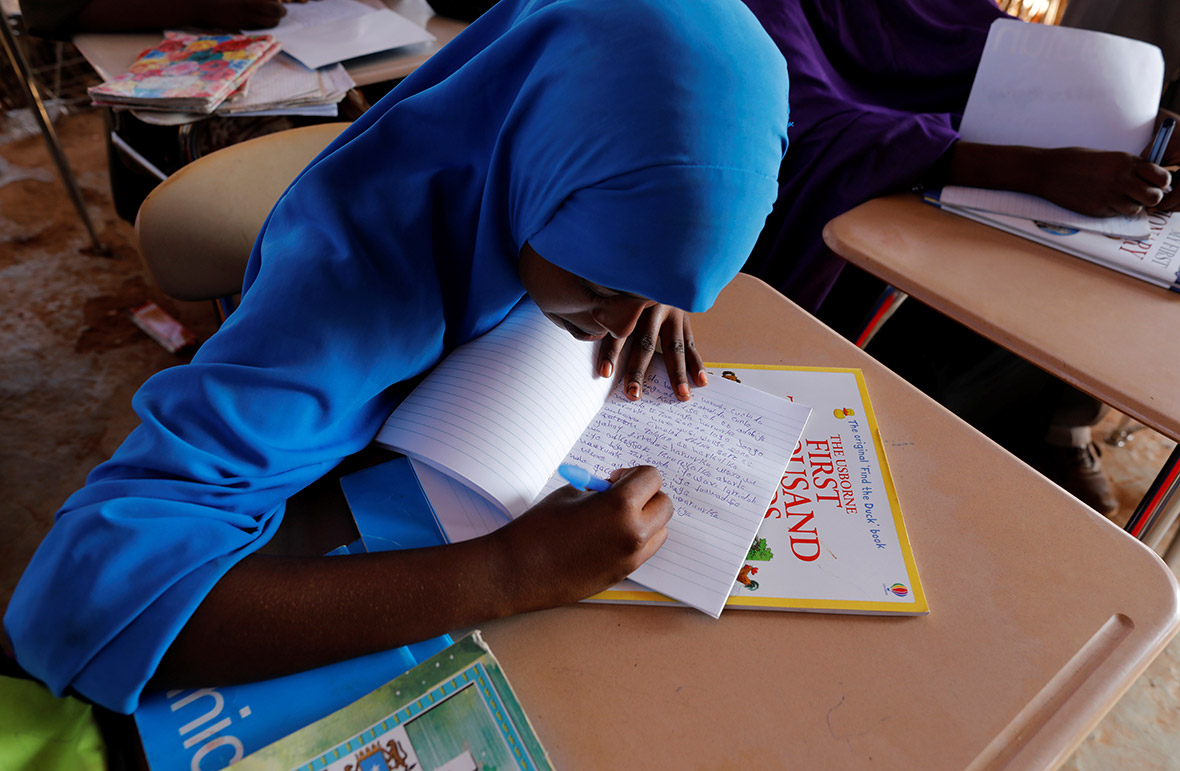

Then Zeinab's English teacher Abdiweli Mohammed Hersi decided to step in. Hersi has seen hundreds of students drop out due to the drought. Five girls this year also left for forced or early marriages, Hersi said. Young, reluctant brides are not unheard of in Somalia, but they are less common in good times, he said, at least in Dollow. "Before the drought, the cases were less," he said, an inflatable globe hanging from the ceiling of his classroom. "Some parents do give their children to other men to get that money."

Hersi took Zeinab to a local aid group, who took her to Italian aid group Cooperazione Internazionale. The regional coordinator, visiting on a trip with EU donors, decided to intervene.

"We must do something for this girl," said Deka Warsame. "Otherwise it will be a rape every night." Her staff held a collection and came up with enough cash to repay the dowry. Warsame told Zeinab the group would mediate a meeting between the men of the two families. Her husband would get back his money if he divorced her in front of witnesses.

Zeinab's dark eyes flicked up from the floor. "Will I be free?" she asked.

This situation is typical of the choices facing Somali families after two years of poor rains. Withered crops and the white bones of livestock are scattered across the Horn of Africa nation. The disaster is part of an arc of hunger and violence threatening 20 million people as it stretches across Africa into the Middle East.

It extends from the red soil of Nigeria in the west, where Boko Haram's six-year jihadist insurgency has forced two million people to flee their homes, to Yemen's white deserts in the east, where warring factions block aid while children starve. Between them lie Somalia's parched sands and the swamps of oil-rich South Sudan, where starving families fleeing three years of civil war survive on water-lily roots.

Parts of South Sudan are already suffering famine, the first in six years. In Somalia, the UN says more than half the 12 million population need aid. A similar drought in 2011, exacerbated by years of civil war, sparked the world's last famine, which killed 260,000 people. Now the country teeters on the brink again.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.