Drug-resistant typhoid superbug threatens global health

After the recent malaria concerns, it is now the turn of an antibiotic-resistant superbug strain of typhoid bacterium that is spreading globally and posing a public health threat.

A landmark genomic study, with contributors from over two dozen countries, and led by Vanessa Wong, an infectious-disease specialist at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK, sequenced the genomes of more than 1,800 S Typhi samples from 63 countries.

The study shows the H58 strain of S Typhi arising from an unrecognised epidemic in Africa is displacing established typhoid fever strains, completely transforming the genetic architecture of the disease.

The resistant strain comprised 47% of the samples and showed widespread resistance to a number of antibiotics, reports Nature.

"Global surveillance at this scale is critical to address the ever-increasing public health threat caused by multidrug resistant typhoid," says Vanessa Wong.

Overuse of older antibiotics has helped drive the H58 epidemic in Africa, believes the team which has also begun to see cases of resistance to newer antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and azithromycin.

Comparing the genomes of the H58 samples suggests that the strain originated in south Asia 25 to 30 years ago, before spreading to the Middle East and the Pacific Islands.

The bacteria also jumped multiple times from Asia into East Africa, and then spread into southern Africa through trade routes.

"H58 is an example of an emerging multiple drug-resistant pathogen which is rapidly spreading around the world," says Professor Gordon Dougan, senior author from the Sanger Institute.

"In this study we have been able to provide a framework for future surveillance of this bacterium, which will enable us to understand how antimicrobial resistance emerges and spreads intercontinentally, with the aim to facilitate prevention and control of typhoid through the use of effective antimicrobials, introduction of vaccines, and water and sanitation programmes."

The latest report comes from Blantyre, Malawi, where 782 cases of typhoid were identified last year, up from an average of just 14 per year between 1998 and 2010. The proportion of infections that were resistant to multiple antibiotics jumped from 7% to 97% over the same period.

"Multidrug-resistant typhoid has been coming and going since the 1970s and is caused by the bacteria picking up novel antimicrobial resistance genes, which are usually lost when we switch to a new drug," says Dr Kathryn Holt, senior author from the University of Melbourne.

"In H58, these genes are becoming a stable part of the genome, which means multiple antibiotic-resistant typhoid is here to stay."

Typhoid is difficult to distinguish from other diseases that cause fever, such as malaria. To confirm a typhoid diagnosis, physicians must collect and culture bacteria from the infected person, a process that takes days and is not always feasible in poor countries.

Causes and symptoms

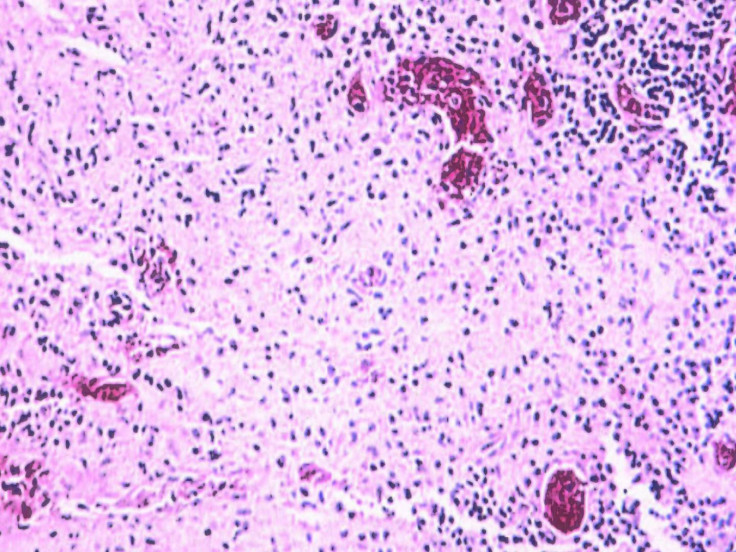

Caused by a variant of Salmonella known as Typhi, typhoid is contracted by drinking or eating contaminated matter and remains a major health threat in developing countries, particularly in areas with poor sanitation.

Symptoms include nausea, fever, abdominal pain and pink spots on the chest. Untreated, the disease can lead to complications which prove fatal in up to 20% of patients.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that there are 22 million cases of the disease each year worldwide.

There are vaccines for typhoid, but they are effective for only a short time and are not widely administered.

Fears over drug-resistant malaria parasite with 40% samples showing clear signs of artemisinin drug resistance in a region close to the India-Myanmar border has recently sent alarm bells ringing of a global epidemic once the strain crosses into India and spreads globally.

As many as 80,000 people could die if there was an outbreak of a drug-resistant blood infection in Britain, with numbers infected as high as 200,000, a recent forecast by the National Risk Register of Civil Emergencies, had said.

Dr Margaret Chan, the director general of the World Health Organization, had warned last year about the dire consequences of emerging drug resistance when she said: "Things as common as strep throat or a child's scratched knee could once again kill."

Indiscriminate and improper use of antibiotics has led to the rising global health catastrophe of drug-resistant superbugs. Antibiotic use has risen by 36% globally during the last decade alone.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.