Election 2015: Brexit is biggest risk to British business not Ed Miliband

Labour has been cast, perhaps unfairly, as an anti-business party. Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, has sought with a number of policies in his manifesto to shake off criticism that he wants to do down business, such as using a 1% rise in corporation tax on big firms to pay for a cut in business rates for small ones.

The party is also committed to clearing the deficit and no extra borrowing to keep public finances and the economy stable, another appeasement for instability-hating business. There are, of course, concerns. Rent controls, energy bill freezes, more labour market regulation, the so-called "mansion tax", ending non-dom status – all come with their respective practical problems for business.

But tax changes and new regulations are, in the scheme of things, mere tinkering that can be reversed overnight. The biggest single risk to British business isn't Red Ed's merry band of raving commies.

It's the Conservatives and their unassailable promise to hold a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union (EU). A risk that threatens two years of economic stagnation before the proposed 2017 referendum is even held and a chaotic exit in the following years if Britons want out.

Arguably membership of the EU is one of the largest 'existential' questions in the general election campaign.

"As we have previously identified, we see a key risk in this election as being how the market assesses the UK's continued membership of the European Union," said a research note from the investment bank UBS.

"The probability of a referendum on EU exit may well result in a period of uncertainty, even if the eventual vote was expected to go in favour of the UK remaining in the EU. In this environment, UK assets may come under some pressure.

"Arguably membership of the EU is one of the largest 'existential' questions in the general election campaign.

"While the costs and benefits of EU membership are actively debated, the market is likely to conclude there would be some cost from exit, or at least uncertainty over the outcome could be a risk for the economy."

Angus Campbell, senior analyst at FXPro, said: "The prospect of leaving the EU after a referendum under a Tory government could send the markets into a tailspin, meanwhile a Labour government could be seen as anti-business and fiscally irresponsible, also causing considerable worry for both domestic and overseas investors."

Labour's position is that it would not hold any referendum on the UK unless there is the prospect of a significant transfer of power away from Westminster to Brussels. This is conveniently vague. But such a prospect, claims Miliband, is very unlikely anyway.

Business backs EU membership

The EU is hugely important to Britain's economy. It gives free access to a market of 500 million citizens, with who the UK does half of all its trading. It allows for the free movement of people, so the UK can plug its skills gaps with European migrants, and vice versa, who academic research shows pay more into the system through tax than they take out in welfare and public services.

Capital can also flow freely between EU borders, making it easier and cheaper for business to get hold of the finance they need to invest in jobs and growth.

Despite the EU's drawbacks – its labyrinthine regulations, an accountability deficit, wastefulness, and so on – business is massively in favour of the single market and the UK's membership of it.

According to a 2013 survey of its members by the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), Britain's biggest business lobbyist, 80% wanted to stay in the EU, though most wanted it to reform by cutting red tape. Similar surveys by the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) have produced similar results.

"Britain's openness to trade, people, investment and ideas from abroad has always been the foundation of our economic success," said a CBI report called First 100 Days, published at the start of the election campaign.

"Today, membership of the EU is the cornerstone of our openness and a springboard to the opportunities presented by the global economy. It is overwhelmingly in our national interest to remain a member."

The City of London also wants the UK to stay in the EU, because free access to the continent's markets means big money for it. And a healthier finance sector means a healthier Treasury purse as it rakes in tax revenues from the City.

The City is scared of the implications of an 'out' vote and about its vulnerability if the UK chooses to go it alone.

A survey by the Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation (CSFI) thinktank of City professionals found that 73% are either definitely or probably going to vote to stay in the EU if there's a referendum.

But 42% thought the European Commission is hostile to the interests of London's finance sector, with 42% saying it's neutral and 16% believing it to be supportive.

"About three or four years ago, when Brexit was just a distant prospect, it had an almost romantic appeal," said Andrew Hilton, director of the CSFI.

"However, our report shows that as a referendum has become more likely the mood has changed – the City is now more worried about short term issues like jobs.

"The City is scared of the implications of an 'out' vote and about its vulnerability if the UK chooses to go it alone.

"That said, support for the EU is based on resignation rather than enthusiasm. Yes, the City wants to remain in the EU, but it doesn't like Brussels, it fears European regulation and it is worried about the political drift of the EU."

Weaker economy, more expensive borrowing

If the Conservatives form a government after the 7 May election, businesses may well decide to defer investment in the UK until after the referendum. Many use the UK as a hub from which they can access the European market, so will be wary of expanding here in case that unfettered access is about to be cut off. Others will be put off of investing money in the UK, or setting up here, because of the inevitable uncertainty.

And it could push up borrowing costs for the UK, as investors shy away from Gilts because of the uncertain political and economic climate. That would mean more money spent on interest payments while the government has to borrow to plug the deficit in its public finances.

"In terms of Gilts, we think the market will focus on two key things," a research note from Nomura said.

"First, a Brexit referendum would not be good for growth in the near term. Whatever you think about the growth impact of an actual Brexit, it seems clear that in the run-up to it the risks are fairly skewed – it is much easier to see business investment falling ahead of the uncertainty rather than rising.

"Second, there is the impact of the uncertainty on non-resident investors. These investors have already started to shun Gilts, according to the data. We believe a Brexit referendum would leave this situation in place for some time."

Once and for all?

The official Conservative position is that it would like to stay in the EU, but that it must be reformed and the British people deserve a say on membership. That is broadly similar to what business itself seems to want – ongoing membership and reform.

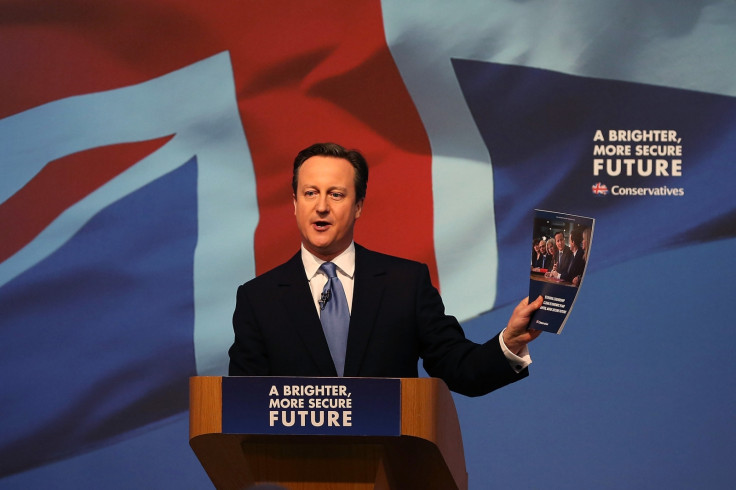

Prime Minister David Cameron offered up a referendum to appease the vociferous eurosceptic element on his backbenches and stave off the threat of Ukip to the Tory vote. He may yet regret that decision. But there are a couple of arguments in his favour for calling a referendum in the first place from the perspective of business.

The EU referendum issue has hung over UK politics for the best part of two decades. There is uneasiness about Brussels among the British public, which sees it as an expensive sapper of national sovereignty. And many are opposed to the free movement of labour after the years of mass immigration to the UK since the EU expanded eastwards to poorer central and eastern European states.

For the ongoing credibility of the EU in the eyes of the British public, it must be allowed a say on whether or not it wants to retain membership. A referendum would settle the issue for a generation at least, giving businesses the long-term confidence that the UK will stay in the EU and shoo away the black cloud of a Brexit.

Miliband may have turned many businesses and foreign investors off by upping the rhetoric against them in the build-up to the election. But what he's promising to do is easily reversed if things went belly up. What the Conservatives are offering is at least two years of uncertainty followed by the prospect of an irreversible, and potentially chaotic, exit from the EU.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.