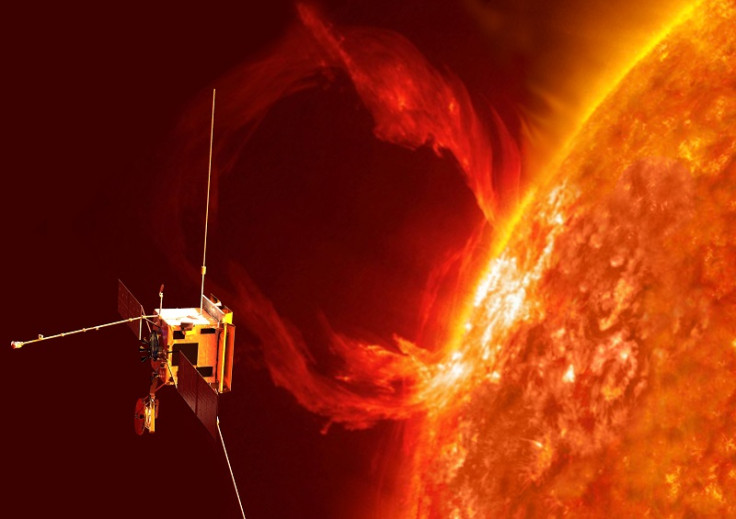

ESA Solar Orbiter probe to explore the Sun in 2020

Next phase of testing begins for the space probe set to study the Sun

The next phase has begun for a spacecraft that aims to boldly go where no man-made object has gone before: the Sun.

The Solar Orbiter will be launched in 2017. It will take more than three years to reach its destination and pass within 42 million kilometres of the Sun, close enough to collect particles that have been propelled from the vast star's surface.

The probe is part of European Space Agency (ESA) study into how the Sun creates and controls the heliosphere: a bubble of space filled with particles and fields, that contains the entire solar system.

The Solar Orbiter will capture high-resolution images of the Sun's surface and deliver data of the side of the Sun that is not visible from Earth, while withstanding extreme temperatures and powerful bursts of atomic particles from explosions in the Sun's atmosphere.

According the ESA, the probe will have to endure sunlight 13 times more intense than that on Earth, and levels of radiation which will push its state-of-the-art equipment to the limit.

If the mission succeeds, the Solar Orbiter will provide valuable insights into major major events caused by the Sun that can cause significant problems for satellites and Earth-based systems. These include coronal mass ejections – bursts of high-energy particles that can cause computers to crash, damage satellites, disrupt electrical power distribution systems and endanger astronauts.

"What causes these events is of fundamental importance," said Chris Castelli, director of programmes for the UK Space Agency, according to the Times. "This is the frontier of scientific research; it is a new era of studying the Sun."

The risks posed to the intrepid craft demand inventive solutions. In order to help reflect the brutal solar radiation, engineers have applied a layer of "pure carbon", made from powdered animal bones, to the outside of the spacecraft's titanium heat shield.

The shield itself consists of an inch-thick layer of crinkled titanium, which then has an 18in (46cm) gap between it and a sophisticated array of lightweight, highly sensitive instruments.

"In that foot and a half the temperature has to drop by 400°C," thermal architect Dan Wild told the Times. "It's crackers."

The Solar Orbiter's STM (structural and thermal model) is set to leave its current home, the Airbus Defence and Space base in Stevenage, on March 23. It will be sent to Munich for three months of mechanical testing before returning to the UK for thermal testing.

The Solar Orbiter will be launched from Nasa's Cape Canaveral base in Florida. The ESA-led mission has strong international collaboration, and is expected to cost close to a €1bn (£710m, $1.05bn).

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.