EU referendum: Why IMF's grim forecast could become reality if Britain votes to leave the EU

The International Monetary Fund's (IMF) negative forecast on the impact a Brexit would have on Britain's economy has some validity, a leading economic consultancy has claimed. On 12 April, theIMF warned that Britain leaving the European Union would lead to severe damage on both a regional and global scale.

In its latest outlook, the IMF said a potential Brexit would threaten established marketing and commercial relationships and would lead to "major challenges" for both the UK and the EU.

Prime Minister David Cameron and the chancellor George Osborne, who both back the pro-European campaign, stressed the report underlined the need for Britain to remain within the 28-country bloc. The Leave camp, however, dismissed the forecast as scaremongering ahead of the European referendum on 23 June.

"The IMF talked down the British economy in the past and now it is doing it again at the request of our own chancellor," said Vote Leave chief executive Matthew Elliott.

"It was wrong then and it is wrong now. The biggest risk to the UK's economy and security is remaining in an unreformed EU which is institutionally incapable of dealing with the challenges it faces, such as the euro and migration crisis."

However, according to research carried out by economic consultancy Oxera, the IMF's forecast could turn out to be true. The firm, which advises multi-nationals, policymakers, international regulators and lawyers on economic issues, said it has reviewed the economic data on the subject and found the common themes it identified are consistent with the IMF statement.

Oxera's analysis shows that there will be a loss of economic output in the "medium term" (over the next five years), due to the uncertainty triggered by a Brexit and the costs and time associated with renegotiation.

"How big this reduction [in GDP] might be is dependent on the type of Free Trade Agreement that the UK is able to negotiate with the EU," David Jevons, partner at Oxera, told IBTimes UK.

"If the UK votes to leave on 23 June, then immediately afterwards there will still be substantial uncertainty as the terms of trade between the UK and the EU will still be unknown. We would expect to see a lot of political effort going into starting those negotiations at that point."

A number of political figures and researchers have indicated one of the major hurdles facing Britain would be renegotiating trade deals. The UK would have to negotiate terms to leave the EU and subsequently would have to establish a new trading relationship with the EU once the UK had left.

Jevons said: "The free-trade agreement between the EU and Canada took seven years to agree and does not cover several important service sectors.

"The Cabinet Office published a report in February highlighting that this could take 'up to a decade or more'. The Leave campaign says that it could be quicker than this but acknowledge it would take time."

A number of economists have suggested that a Brexit could lead to a break-up of the United Kingdom and Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, has already suggested that Scotland could demand a second independence referendum should Britain vote to leave the EU.

Jevons believes the possibility of Scotland securing a second referendum and subsequently voting for independence is very real.

"It is conceivable that Scotland could secure a second referendum on independence and vote to leave the UK," he said. "In this scenario, Scotland could then apply to join the EU as an accession state. This would increase the uncertainty surrounding the UK as it negotiates a trade agreement with the EU."

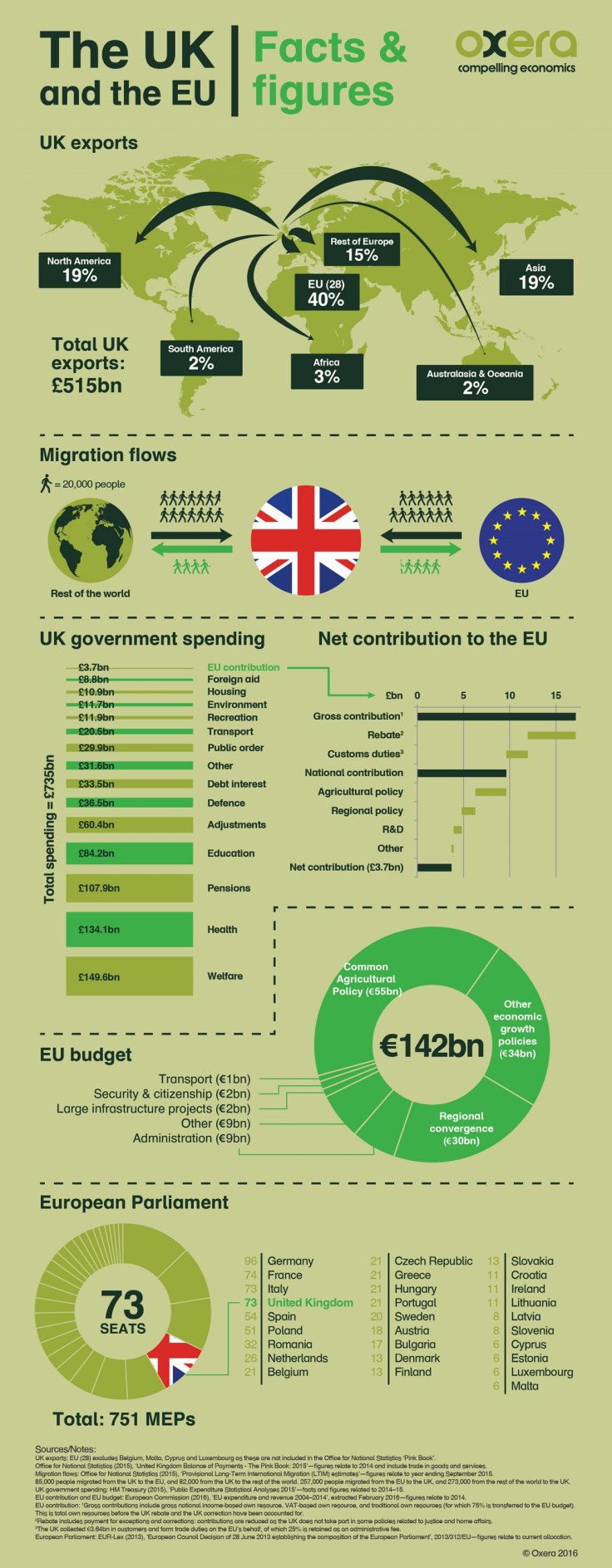

One of the key issues around the referendum is whether Britain's economy would benefit from leaving the EU, in which case it will not have to contribute to the EU budget, ostensibly saving around £9.6bn per year.

However, exiting the EU would also mean Britain would be inelegible to receive various benefits from EU policies relating to agricultural, regional and R&D policies, which amount to about £5.9bn. Therefore, the amount the UK government would have available to spend depends on how many of the EU policies it chooses to replicate.

"If the government matches the benefits provided to the UK it would, all other things being equal, have around £3.7bn per year to spend," Jevons added.

"If the UK were to not replace all of these benefits then it would potentially have around £9.6bn per year. To put that in context, the UK government spends £8.8bn on foreign aid and £10.9bn on housing."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.