GCSE results: Our obsession with exams is why our children are failing in the world of work

Employers care much more about pupil's character and social skills than about grades.

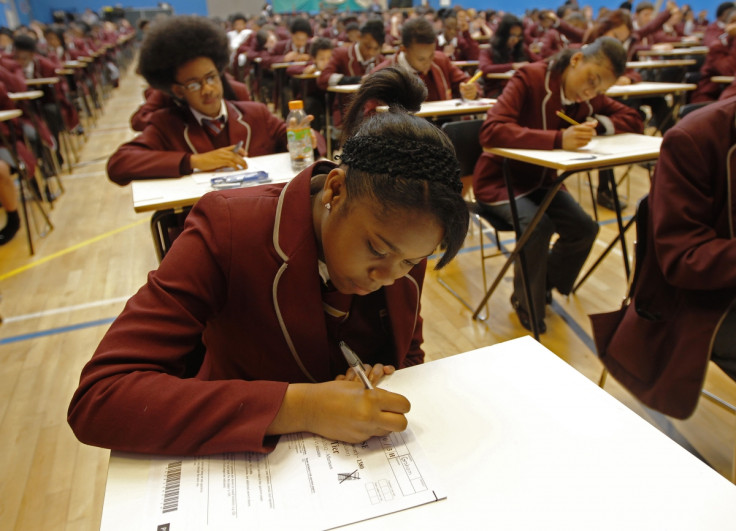

It is that time of year again. England, Wales and Northern Ireland's 16-year-olds, and their parents, are nervous. Teachers and senior leaders in schools know their reputations, pay – and in some cases, jobs – are at stake.

Taxpayers want to know what they are getting for their money.

And journalists need a reliable story to fill pages during the silly season.

The rituals of GCSE results day are familiar. A raft of figures, including the overall pass rate and variations according to subject, gender and ethnic group, will be published. There will be the usual self-congratulation, as we hear that government policy, the OFSTED inspection system or the latest gimmick in your local school are working.

Most people will soon forget the details. The children affected – who must now stay in education or training until they are 18 – will move on to another round of qualifications. But in the nation's staff rooms, the figures will be the big event of the year.

Teachers will complete detailed exam analyses: official-sounding documents which will remain largely unread. Policy makers and senior leaders will set new targets for the next set of children. By a stroke of genius worthy of at least a C in Maths, they will say success means the numbers going up a bit.

This year the process will be further complicated by Progress 8, a new government system for measuring schools. The good news is this will reduce the incentive for schools to chase C grades at the expense of all else. The bad news? Many hours are about to be wasted over a hopelessly convoluted, data-heavy attempt to compare schools' results by measuring the progress children have made between the ages of 11 and 16.

We should stop obsessing over this non-event. On a national level, it reveals little more than how well schools are gaming the latest system. Our priority should be to consider how well prepared young people are for life after school. And for an insight into that, we should pay more attention to another, newer summer ritual.

Those who hire and work with Britain's young people told us in stark terms that too many had negative attitudes to work.

In July, the British public was told that "an emphasis on GCSE grades and school league tables has too often distracted from the need to support each and every young person as they develop core capabilities". Schools needed incentives to "focus on more holistic development". Accountability mechanisms should be changed.

This might sound like the repetitive drone of a disgruntled old-timer at your child's school. In fact, it was the verdict of the CBI, in their annual report on the state of national skills and education.

The report made clear how little GCSE results matter outside the education bubble. In one survey, 89% of employers said "attitudes to work and character" were among their most significant concerns when recruiting school and college leavers. Just 36% mentioned "qualifications obtained".

Employers were also asked what they made of school leavers' skills and attitudes. On seven out of 15 questions, at least 50% were "not satisfied'". The figure for "very satisfied" was below 10% for everything but IT skills. Those who hire and work with Britain's young people told us in stark terms that too many had negative attitudes to work, were insufficiently able to manage themselves and could not communicate.

Graduates were given a more encouraging hearing on a parallel survey. But three in 10 employers believed even youngsters who had been to university lacked self-management skills; four in 10 were unhappy with their business and customer awareness; more were "not satisfied" than "very satisfied" on 11 of the 15 questions.

The mentality that schools live or die by their exam results is helping to create these problems. We have not only neglected crucial attitudes and skills which are tricky to measure. We have hindered their development by piling pressure on teachers to drive the numbers up. Young people are brought up to think they are consumers and someone else will do everything for them. And when they leave school, they bring the mentality of revision guides and extra lessons for disruptive students into the workplace.

The cult of the GCSE result bears little relation to the world our 16-year-olds will soon enter

We are also breeding an over-qualified generation. We tell children at an ever-younger age that tests will set them free. But, according to one report last year, three in five UK graduates work in jobs that do not require a degree. Only 55% of the CBI's respondents cared about graduates' degree results; 87% were interested in their "attitudes and aptitudes for work".

Young people need to do tests – they are a rite of passage which help to teach them discipline and give them structure. And teachers must be held to account on behalf of the next generation. But watch today's news, and you will witness the cult of the GCSE result. It not only bears little relation to the world our 16-year-olds will soon enter; it is creating a parallel universe which is shielding them from reality.

Chris Sloggett is a former teacher and a writer at The Day. He is currently writing a book on target culture in education.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.