George Osborne kicked the poor and accelerated Britain's decline — he was never a moderate

Liberal conservatism is dying at the hands of populism but progressives shouldn't mourn.

For all the talk of the 'Osborne supremacy' a few short years ago, liberal conservative hegemony was never as embedded as many pundits liked to think. That much has become self-evident of late.

It is easy to forget it now that Theresa May is the prime minister and David Cameron feels like a long-lost uncle from a PG Wodehouse novel, but until very recently triumphalist screeds were being written to mark the passing of Tory social conservatism into the wastepaper basket of history along with similarly redundant creeds like Butskellism.

Yet while the 'nasty party' may have been buried the coffin stayed empty. Cameron may have been issuing liberal platitudes from Number 10, but judging by the zeal with which the party has subsequently embraced Brexit it was evidently Nigel Farage who was calling the shots on the Tory backbenches.

It is therefore tempting to view the brief period of liberal conservatism – an era when Tony Blair was quietly referred to as 'The Master' by Tory modernisers – through rose-tinted spectacles.

It is especially enticing to look back on the previous Conservative government – in particular its Chancellor George Osborne – in a warmer light now that the post-Brexit political divide is supposedly between those who are 'open' versus those who are 'closed'. Left and Right are redundant, or so it is said, and Osborne – a liberal-minded Remainer – has supposedly become one of us – an opener, and a Tory bulwark against the Little Englanderism which, among other bonkers moves, is currently agitating for war with Spain.

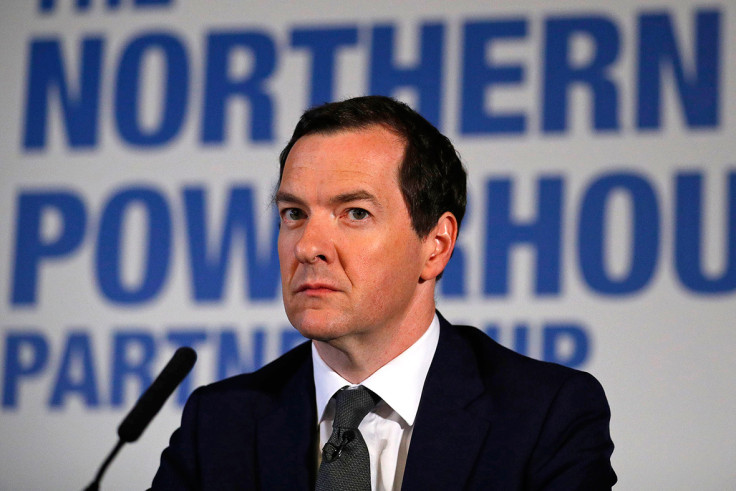

Yet this week offers a timely reminder as to why Britain's former chancellor should not be retrospectively written into the history books as a 'moderate' or 'centrist' by those desperately scrambling around for allies in the fight against wild populism.

According to new analysis by the Resolution Foundation, plans set in train by Osborne before he was deposed will see tax and benefit changes come in that will reward high earners while penalising those claiming benefits. The £1bn net giveaway, announced two years ago as part of Osborne's deficit reduction plan, will see better off households receive four-fifths of the gains while the poorest third will be the worst hit.

The analysis put out by the Resolution Foundation matters because there is a direct line from the misery inflicted on many 'left behind' voters by George Osborne's economic legacy and Britain's act of self-harm in voting to leave the European Union (EU), an issue on which Osborne is supposed to now be an ally.

A charitable reading of Osborne's legacy would say that the harshness of his economic agenda simply matched the gravity of the financial situation Britain found itself in back in 2010. To briefly rehash the arguments from back then: Britain's finances were in a precarious state and what the poor and downtrodden required was tough love. The road to welfare dependency is after all paved with good left-wing intentions which invariably lead to profligacy – profligacy which the Conservatives, who are made of sterner stuff, must clear up.

The trouble is that Osborne's idea of 'tough love' never did work out quite as he had intended. Despite the brief uptick in the British economy at the tail-end of the last parliament and the beginning of this one, the economic recovery from the crisis of 2008 was slower in the UK than in both the US and Japan. Price-adjusted GDP per capita in Britain by the time of the Brexit referendum remained lower than where it had been before the crisis in 2008.

As for the initial panic which triggered the fanatical wave of cuts, the ratio of public debt-to-GDP was in fact far smaller during Osborne's reign as chancellor than in the two decades after the Second World War, when it prompted very little hyperbole about 'living within our means'.

Looked at in this light, the Osborne supremacy looks more like an opportunistic dash to radically shrink the size of the state. The burgeoning demand for food banks and the six-consecutive yearly rise in rough sleeping that happened during his stewardship of the economy tell their own story. But then, as the former Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg has claimed, it "didn't really matter [to Osborne] what the human consequences were".

To drive the meaning of all this home, take a cursory look at the impact of Osbornomics on working class areas of Britain. Towns which voted Leave often did so against a backdrop of sharp economic decline which George Osborne and David Cameron at the very least failed to halt.

When I recently travelled around the South Wales valleys, many of the locals were quick to blame the economic decline of recent decades on the EU. As one elderly man called Robin put it to me in Cwm, "I think [the anti-EU sentiment] is probably because they lost their steelworks here, and they see Port Talbot under threat as well, and I think it's just a backlash from that".

I heard variations of this sentiment wherever I travelled.

The industrial vandalism meted out by Thatcherism is well established. It is less well known that Cameron and Osborne's business secretary, Sajid Javid, lobbied vociferously against attempts at a European level to tighten up the 'unfair trading practices' that allowed Chinese state companies to dump masses of cheaply produced steel on European markets – further destroying the profitability of British steel in the process.

Travel to parts of the Midlands or the north-west today and you will find a similar story: thriving manufacturing and industry has been replaced by fulfilment warehouses and call centres offering unpromising agency work for the minimum wage.

George Osborne did not cause the decline (and to his credit he raised the minimum wage) but his legacy will have been to hasten it, however many attempts are made to retrospectively define his and Cameron's project as one of the centre ground. The 'march of the makers' and the 'Northern powerhouse' – two concepts which Osborne talked about incessantly during his final year in office – today sound like cheap gimmicks: the UK's balance of payments deficit in the final quarter of 2015 sat at a record 7% of GDP. In April of last year – just two months before Cameron and Osborne were unexpectedly booted from office – British manufacturing activity shrunk at the fastest rate for three years.

Osborne's time in the Treasury smoothed the way for Brexit like the sweeper warms the path of the stone in a game of curling.

His great insight – that the rich will only work if you give them money while the poor will only do so if you take it away – is no insight at all, but is merely a contemporary repackaging of an older aversion to the working class that still simmers away behind the modern Tory visage like a hot pan of coals.

Osborne's partial rehabilitation among a certain kind of liberal says more about the type of politics that will once again pose the biggest challenge to progressives when the alt-right has given itself a collective embolism: a conservatism which tilts at Thatcherite windmills while mouthing all the correct socially liberal platitudes.

Genuine progressives should not mourn the temporary death of liberal conservatism, even if its successor regime is in many respects worse. There has never been anything modernising or brave about kicking the poor.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.