Government kept 450 files secret in 2016 - what has it got to hide?

Historians need official documents to tell the truth about the past - without full disclosure there is only a partial picture

The latest batch of Cabinet Office records released on 21 July – covering the years 1986 to 1988 – promised much but delivered little. Just over 1,200 files have been 'released' but over a third of them – some 450 – have not.

Many of the releases are non-controversial and simply cover the normal workings of government such as the prime minister's visits abroad, policies on education, energy, Europe, health, and gas and electricity pricing.

The National Archives Press Department has helpfully highlighted certain files that have been retained, including those dealing with immigration rules, the situation in the Middle East, briefings on economic policy and on UK participation in the European Monetary System.

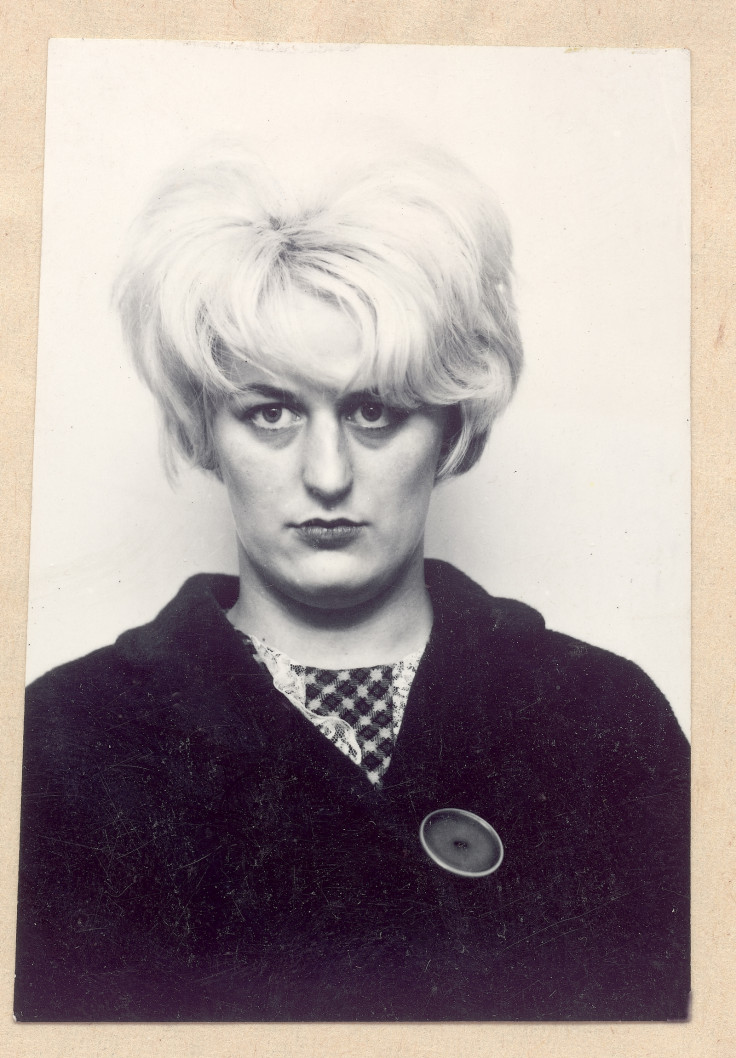

But the really interesting material can only be found by going through the complete list of retained files. Here we find documentation on the parole position of Myra Hindley and Ian Brady, discussions on the future of Hong Kong and the activities of the Paedophile International Exchange.

There are also files on spy cases such as Geoffrey Prime, Michael Bettaney, a history of the wartime organisation SOE and 32 files on the 1987 Peter Wright Spycatcher case. In one particularly galling case, documents relating to the cementation contract between Mark Thatcher and the Omanis has been closed for a further 65 years – when he will be 128.

Even files ostensibly of little controversy remain closed, including briefings and appraisals on the Iran-Iraq War, Ireland, the Soviet Union, six of the seven files on Anglo-American relations and documents dealing with UK and Japanese trade relations.

The list continues: discussions over shipbuilding policy, the internal situation in Nicaragua, the Duke of Kent's marriage in 1986 and proposals relating to the papers concerning the Abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936. And my favourite: the 1983 government discussions on 'Open government and freedom of information'.

Some of the files go back much further such as Lord Denning's 1963 Inquiry into the Profumo Affair but whilst the press cuttings – already available for the last fifty three years – have been released, the transcripts of evidence, police documents, letters from various sources and post inquiry papers remain closed for another eighty four years. It is difficult to understand this justification since the youngest person involved in the case would now be in their eighties.

Bizarrely some material is retained even though it has been publicly available for years, such as Margaret Thatcher's parliamentary statement regarding allegations made against former head of MI6 Maurice Oldfield, even though her speech was first printed in Hansard twenty nine years ago.

By retaining so much material the Government is making a mockery of its obligations under the Public Records and Freedom of Information Acts. Even if any of the retained material can be seen to be damaging national security or breaching data protection rules, there is always the option of redacting names or particularly sensitive material.

The Government made great play last year of releasing four hundred files on Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean – a spy case dating back to 1951 – but the releases added little to what we already know and many more files have still to be made public.

I had already discovered from interviews that the Government knew about the escape three days before the official line and in my book on the case revealed a hitherto unknown spy in the Washington Embassy – a graduate of London not Cambridge University – from research in the private papers of a senior Foreign Office official. There is nothing in any of the releases which refers to either disclosure.

One of the ironies is that the Cabinet Office, which is responsible for supervising the Freedom of Information Act across Whitehall, is one of the most flagrant transgressors when it comes to the release of documents. From my own experience, they often simply do not reply to requests, invariably impose blanket exemptions and, even when they are forced through challenges to release material, take their time to lodge documents at the National Archives.

A file on Anthony Blunt which I successfully forced them to release over a year ago has still not reached the National Archives. Another on Lord Mountbatten comprised three sheets of paper, none of which referred to the title of the file. After a year long fight to secure a document, I was told it was being retained because of mould.

It is not generally known that, in fact, the vast majority of historical files are neither released nor retained – they are simply destroyed. Government departments keep lists of them but they refuse to make them public. So much for claims of transparency and open government.

Even once they are supposedly sent to the National Archives many go missing. According to a recent report over four hundred government documents including files on "military and nuclear collaboration with Israel: Israeli nuclear armament" and a Foreign Office dossier from 1963 on Greville Wynne a British businessman held by the Russians on allegations of spying remain unaccounted for since 1 January 2012. In 2011 it emerged that one thousand six hundred files had been reported lost from the National Archives in the previous six years.

Historians need official documents to tell the truth about the past. For some, such as intelligence historians, it is very important. Without full disclosure, there is only a partial picture.

Yet historians in public life appear unconcerned and government departments are not being properly held to account. My approaches to historians in both houses of Parliament yielded one response from a member of the House of Lords After tabling one question and being fobbed off he did nothing further. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Archives and History is low profile. The Advisory Committee on Records at the National Archives, appointed by the Lord Chancellor and largely filled by retired civil servants, meets occasionally and has not addressed any of these issues.

Six months ago I met the two ministers responsible for records – Matt Hancock and Ed Vaizey – and they expressed determination to address some of these issues, notably that there is no public interest defence and government departments need not justify withholding files beyond simply stating they are being withheld on grounds of national security, data protection or because they may affect foreign relations. I have not heard from them since and they are no longer in those roles.

Let us hope that with the appointment of Ben Gummer – a Cambridge starred first in history and author of an acclaimed book on The Black Death – as Hancock's successor as the minister responsible for the Cabinet Office that historians will be better served in the future though I am not holding my breath. He has yet to respond to any approaches.

Andrew Lownie is a historian and author of Stalin's Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.