He Named Me Malala: Violence, poverty and child marriage deny girls their education rights

Malala Yousafzai was given her first name after Malalai of Maiwand, a Pashtun poet and warrior from southern Afghanistan, and it could not have been more accurate. It has only been six years since the Pakistani schoolgirl wrote an anonymous diary about life under Taliban rule in her native Swat Valley.

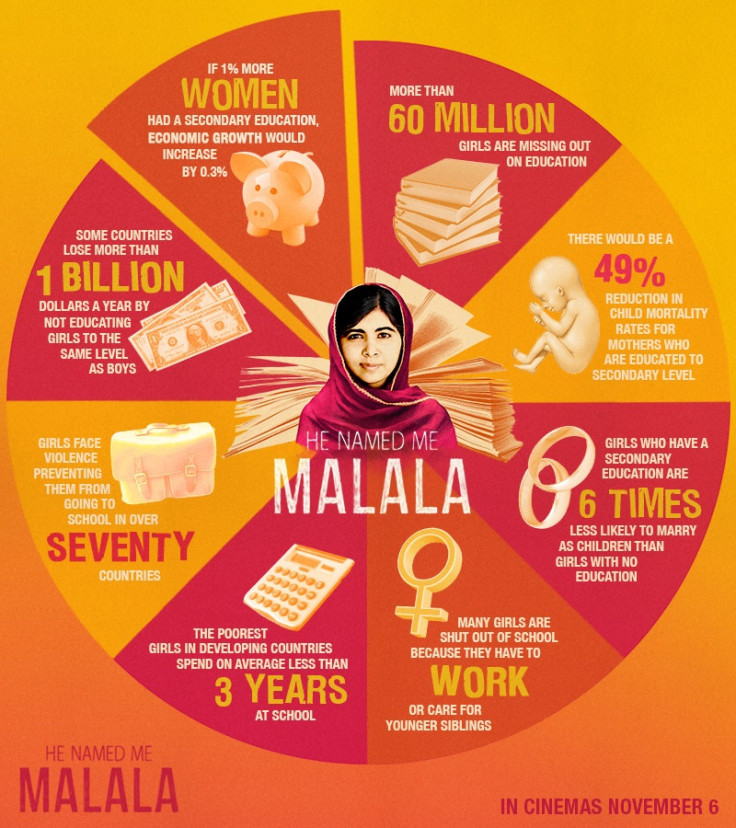

Since then, she has been shot in the head by the militants, taken her campaign for girls' education global and become the youngest person in history to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. And on 6 November, a feature-length documentary of her story will be released in the UK.

Yousafzai's story has brought the problems girls face in getting a quality education to light. Education is a key human right, but around 62 million girls do not go to school because of poverty, conflict and discrimination. Those denied this opportunity miss out on the chance to thrive, become independent, build self-confidence and become financially self-sufficient. When a girl is taken out of school, whether to go into work or get married, it often cements the end of her ability to make her own choices regarding her future.

Violence is one of the biggest problems holding girls back from achieving a decent education and finishing school. An estimated 150 million girls around the world have experienced sexual violence – much of which is said to take place in schools. Recent research commissioned by charity Plan UK found 50% of girls they spoke to felt unsafe using toilets in schools, while 47% said they felt unsafe on their way to schools because of the threat or fear of physical, sexual or verbal abuse.

Yousafzai's shooting is an extreme example of this, as is the abduction of hundreds of schoolgirls in Nigeria by Boko Haram. Despite the global Bring Back Our Girls campaign, which spread across the world via social media to garner support from millions, more than 200 of the girls have not yet been found. Chibok was not the first abduction of schools either – according to Amnesty International, at least 2,000 women and girls have been abducted by Boko Haram since the start of 2014.

Violence is not the only problem girls face – and many different issues are interconnected to poverty. Early marriage, or child marriage, often spells the end of a girl's education – and one third of girls in the developing world are married before the age of 18. One in nine are married before age 15.

Many girls aren't in education because schools are expensive or inaccessible, but also because in communities where a dowry is paid, it is often welcome income for poor families. In those where the bride's family pay the groom a dowry, they often have to pay less money if the bride is young and uneducated. In some cases, girls are married off because their family believes it will keep them safe in areas rife with sexual or physical violence.

As the result of adherence to traditional gender roles, many girls suffer the burden of work – paid or unpaid – which hinders their chances of a good education. Denied the chance to learn the skills they need to lift them out of poverty, girls are locked into destitution.

Since 2009, there have been almost 10,000 attacks on places of learning – in countries including Syria, Pakistan, Nigeria and Colombia. War Child estimates there are almost 40 million children out of school in conflict-affected countries, because buildings have been destroyed, teachers were killed or forced to flee and because basic healthcare systems have been obliterated, leaving children defenceless against disease.

Aside from the benefits for each girl, having access to a good education is crucial for societies and economies. Research tells us just one extra year of secondary education boosts a girl's eventual income by 10% to 20%, while the World Bank reports that young women are likely to reinvest up to 90% of their income in their families and communities – chipping away at the cycle of poverty. This is why the Malala Fund is campaigning for every girl to complete 12 years of safe, quality education so they can achieve their potential and be positive change-makers.

He Named Me Malala will be released in the UK on 6 November.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.