How Israel became a battering ram in the fight for the soul of the Labour Party

The question of Israel and Palestine has always divided the left.

If today's Labour Party appears to be reliving the 1980s, right down to the Jeremy Corbyn's choice of musical endorsement, then it should be no surprise that attitudes to Israel, Jews and Zionism have become part of the argument about where the party is heading. Support for the Palestinian cause might be relatively common across the left nowadays, but it only made an appearance in Labour Party policy in the 1980s.

Labour supported Israel's creation in 1948 (as did most of the left) and was generally pro-Israel thereafter.

But in the 1980s, the rise of the Labour Left brought with it radical ideas about the elimination of Israel that had previously existed only on the radical fringes of left-wing thought.

Labour's deputy leader Tom Watson won't be surprised that this was partly due to a growing Trotskyist influence. Ted Knight and Ken Livingstone, respective leaders of Lambeth Council and the Greater London Council, were part of a discussion group that met at the flat of Gerry Healy, the diminutive but vicious leader of the Workers Revolutionary Party. It was Knight who moved a successful motion at the 1982 Labour Party conference calling for "the establishment of a democratic secular state of Palestine": not alongside Israel, but instead of it.

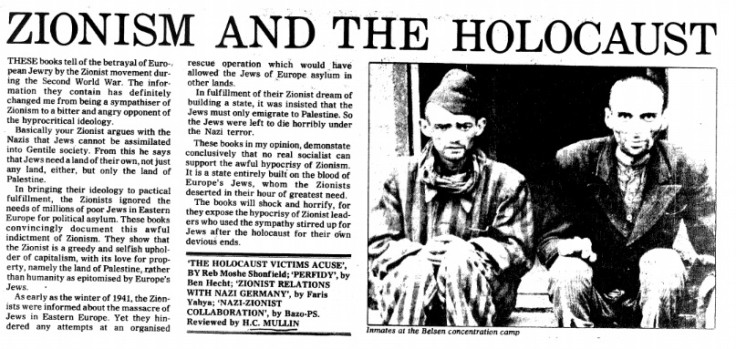

One outcome of those late night chats was the Labour Herald newspaper, edited by Livingstone and Knight, launched with funding from the Palestine Liberation Organisation and printed on presses provided by Colonel Gaddafi's Libya. Think Livingstone has only recently developed his strange interest in Hitler and Zionism? Think again. Labour Herald published articles claiming that wartime Zionists collaborated with Nazis and ran a cartoon of then-Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin in an SS uniform giving a Nazi salute.

While this was going on in the main party, on campus Labour Students were fighting similar battles over the decision of Sunderland Polytechnic Students' Union to ban its Jewish Society. The thinking in Sunderland was that the Jewish Society was Zionist, Zionism was racist, and racism was subject to the union's "no platform" policy: so out goes the Jewish Society. The fact that this outcome was anti-Semitic passed many people by.

The head of Labour Students at the time was John Mann, who is now Labour MP for Bassetlaw and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group Against Antisemitism. He backed the Jewish Society against anti-Zionists within Labour Students and in other student factions. By winning that fight he also secured his own position against his Trotskyist opponents. In the main Labour Party and amongst its students, Zionism and anti-Zionism were markers of where you stood on the left.

This wasn't the first time that Jewish Societies had been banned by British Students' Unions under the "Zionism is Racism" formula. In the 1970s it was Trotskyists and Maoists who pushed for the bans, and Communists and Socialists who opposed them. The Communist leadership of the National Union of Students would not pass up an opportunity to "smash the Trots", as David Cesarani, then the political officer of the Union of Jewish Students and later an eminent historian of anti-Semitism, put it, and Zionism was a battleground on which they did it.

The question of Israel and Palestine has always divided the left. Labour MP Fenner Brockway, who was one of Britain's greatest anti-colonial campaigners, said he was more puzzled by Israel/Palestine than by any other issue. Assessing the competing claims and rights of Israelis and Palestinians is made more complicated by the shifting politics of Israel, a state that was founded by socialists out of the horror of the Holocaust (with Soviet support) in 1948 and has evolved into a local superpower allied to America that has occupied the West Bank for almost 50 years.

Zionism and big business: it's not hard to see how anti-Semitism can slip in through the back door.

Fast forward to the current problems in Labour and there is no greater and more toxic divide than the legacy of Iraq. Here, too, attitudes to Israel and Zionism play their part. When the Stop The War Coalition (STWC) organised Britain's largest ever political demonstration against the war in February 2003, their Islamist allies from the Muslim Association of Britain insisted on adding "Freedom for Palestine" to their banners and placards. This has stuck and Israel is now the only country in the world, other than the UK and US, whose conflicts interest STWC and its supporters.

This was never just a project to oppose war. Shortly after STWC was founded, its chair (and now chief of staff at Unite) Andrew Murray predicted that "In fighting for peace, and against imperialism, we are also fighting for our own future and our own freedom. By defeating New Labour and the class interests which it serves, we will also be opening up our own road to Socialism." After Corbyn became party leader, Murray crowed that the path to victory was paved by STWC.

Opposing Zionism became wrapped up with opposing Blair, who was very much a Labour Zionist. New Labour was also associated with a friendlier attitude to wealth creation and big business and, well, you know what people say about Jews and money. Zionism and big business: it's not hard to see how anti-Semitism can slip in through the back door.

It seems trite to say that Jews might feel unwelcome in such an environment. The bigger question is how everyone else feels about it: and where they stand on that, will tell you a lot about their vision for the future of the Labour Party.

Dave Rich is author of The Left's Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.