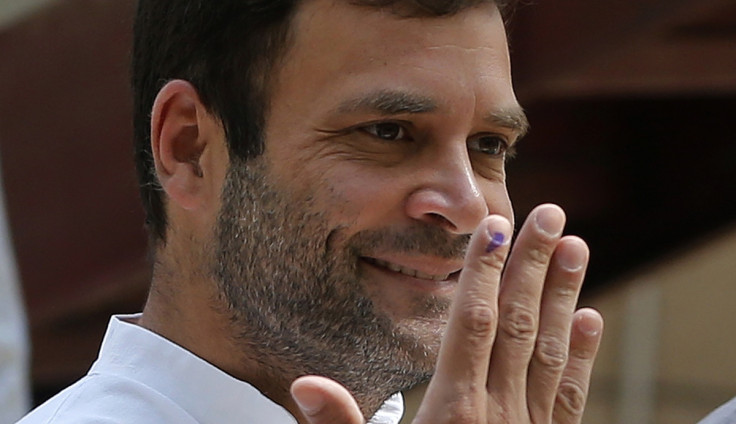

India Elections 2014: The Grim Unravelling of Rahul Gandhi

Rahul Gandhi has just burnished his 'reputation' once again by presiding over another Congress party debacle, in regions which were once akin to a personal fiefdom for his family.

In the 2012 elections, he was the "face" of the campaign -- as mindless dynasty sycophants would put it – in the mammoth Uttar Pradesh state, and he and his party squarely lost it, ending up in fourth place with a paltry total of about 10% total seats.

Before that, in 2010, he was tasked with reviving Congress's fortunes in another former bastion, Bihar state. But he failed miserably.

In 2014, the unstoppable Modi wave has erased even the vestigial presence the party had in Uttar Pradesh, the key state which houses 80 parliamentary seats.

The state, from whence generations of Gandhi politicians won their key electoral battles, will in all probability return only two Congress candidates – Rahul Gandhi himself and his mother Sonia, the widow of slain former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi.

Congress decimation across India means the party, which ruled the country for most of the post-independence era, is facing the ignominy of not even being the main opposition in parliament.

This will be the "unkindest cut off all" for Gandhi, who took it upon himself to regain Congress glory in the Hindi heartland of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.

In this election too, Gandhi might have been a reluctant leader (but for that matter he has always been a "reluctant somebody") but circumstances offered him no respite.

He had to be in the foreground, facing live fire. With Prime Minister Manmohan Singh quietly crawling into an ignominious sunset after 10 years of botched opportunities, there was no-one else in his party to "lead" a campaign destined to fall flat on its face.

But the 43-year-old did put up a brave face and fought valiantly. And he did come across as a lovable person with honest intentions and zest for the improvement of people's lives. He was the embodiment of energy, darting through barricades to shake hands with people, refusing umbrellas to walk gingerly in pouring rain – and more importantly, speaking honestly and looking comfortable doing so (in politics that is a feat in itself).

Probably that level of honestly contributed to his undoing, for in realpolitik it's called plain naiveté.

The baggage of the past sat uncomfortably on his back along the campaign trail and he didn't have clear answers as to why his party, which ruled for the country for six decades, could not strive to bring the changes that he now championed.

He tried to paint himself as a dispassionate outsider who is on a mission to deliver the country from ills like corruption and poverty. But he couldn't really come across as an outsider and his opponents drilled home the idea that he has been on the inside track like no-one else.

And in this election, Gandhi had to face another other, stiffer, challenge too – the incredibly well-functioning media campaign of Narendra Modi, whose brutally efficient thinktank, speech writers and social media rabble-rousers started deconstructing his every utterance.

Soon the young, well-intentioned leader's tall promises became hollow chants, his gaffes just a proof of his naiveté, his honest mistakes blown up to show he was dumb and his speeches interpreted as revealing someone wet behind the ears.

The Modi campaign systematically portrayed Gandhi as a privileged kid with no connection to real India. They tarred him as the prince who goes on picnics to see what poverty is. And when he used metaphors in speeches, the Modi speechwriters immediately hammered home the innuendo, portraying Gandhi as a child playing with balloons or hankering after toffees.

While such clever, sustained broadsides dented his political personality, that was obviously not the full reason for his phenomenal unravelling as a national leader.

Several people around him failed him. The party cronies who did not tell him tough home truths; the prime minister who cut a sorry figure in the second term; a string of ministers and senior party leaders whose corruption tainted the government, the allies who jumped off the sinking ship at the opportune time, the economic policy that failed to bring back the zest but funnelled money into wasted welfare programmes instead – the list goes on.

Now, what does the future hold for him? Will he choose to deliver the change that he preaches, and let the Grand Old Party go forward without a Gandhi presiding over it?

It would be interesting to see how he deals with this biting loss, standing in the electoral graveyard of his country's political royalty.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.