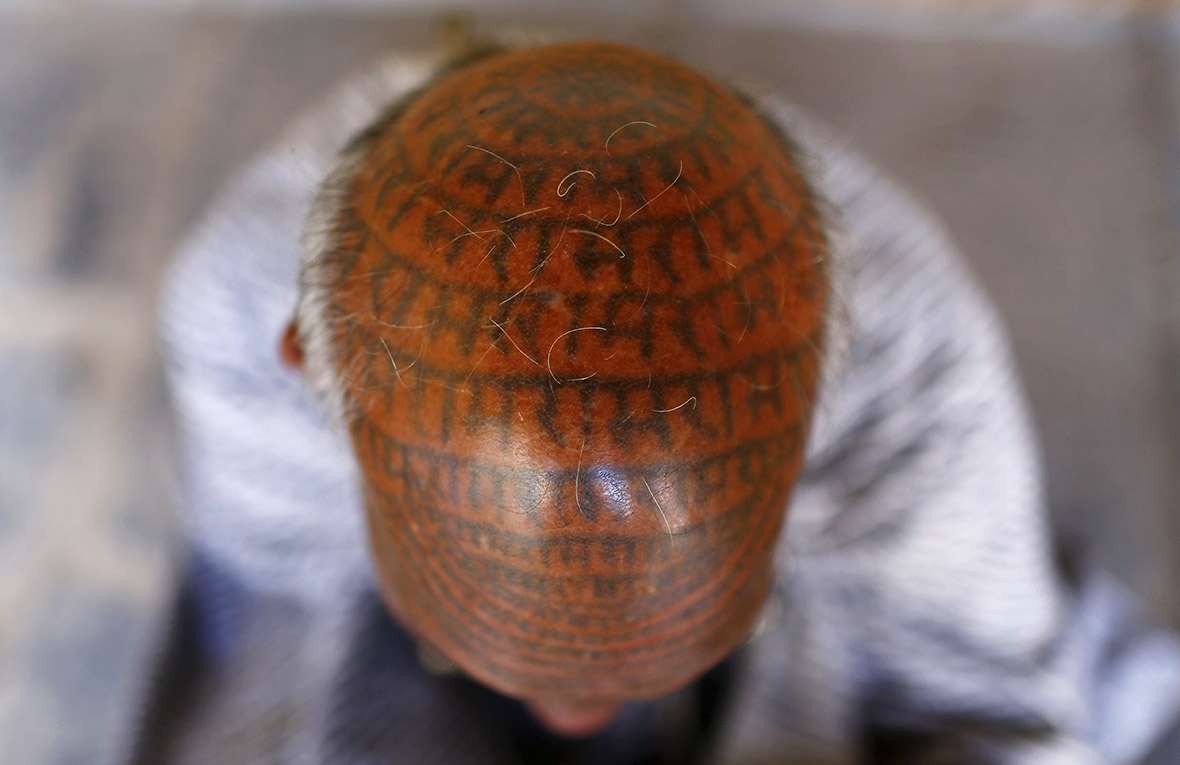

India: The intricately tattooed bodies and faces of low caste Ramnami Samaj Hindus

Low-caste Hindus in the eastern state of Chhattisgarh first began tattooing their bodies and faces more than 100 years ago as an act of devotion and defiance after being denied entry to temples and forced to use separate wells. Ramnamis, as followers of the Ramnami Samaj religious movement are called, first wrote the Hindu god Ram's name on their bodies as a message to higher-caste Indians that god is everywhere, regardless of caste.

Mahettar Ram Tandon, who lives in the village of Jamgahan, is proud of the indelible message he carries almost five decades after he had the name of Ram tattooed on his entire body. Dressed in a simple white lungi and wearing a peacock feather hat called a "mukut", Tandon told Reuters: "It was my new birth the day I started having the tattoos. The old me had died." Now 76, Tandon's purple tattoos have faded over decades under the harsh sun.

Nowadays the tattoos of Ramnamis, who number 100,000 or more in dozens of villages spread across Chhattisgarh state, are usually on a smaller scale. After caste-based discrimination was banned in India in 1955, the lives of many lower-caste Indians have improved, villagers said. As young Ramnamis today also travel to other regions to study and look for work, younger generations usually avoid full-body tattoos.

"The young generation just don't feel good about having tattoos on their whole body," said Tandon, who has always lived in his village of small mud houses surrounded by fields of grazing cattle, wheat and rice. "That doesn't mean they don't follow the faith."

In the nearby village of Gorba, Punai Bai spent more than two weeks aged 18 having her full body tattooed using dye made from mixing soot from a kerosene lamp with water. Now aged 75, Bai, who lives in a one-room house with her son, daughter-in law and two grandchildren, said: "God is for everybody, not just for one community."

Children born in the community are still required to be tattooed anywhere on their body, preferably on their chest, at least once by the age of two. According to their religious practices, Ramnamis do not drink or smoke, must chant the name "Ram" daily, and are exhorted to treat everybody with equality and respect. Almost every Ramnami household owns a copy of the Ramayana epic, a book on Lord Rama's life and teachings, along with small statues of Indian deities. Most followers' homes in these villages have "Ram Ram" written in black on the outer and inner walls.

Despite the 1955 legislation, centuries-old feudal attitudes persist in many parts of the country and low-caste people, or Dalits, still face prejudice in every sector from education to employment. Tandon is optimistic about the Ramnamis' relative change in fortunes since he had his body tattooed all those years ago. "The world is changing, the times are changing," he told Reuters. "We have all realised that we are all same."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.