Isis: Draconian regime of Islamic State will persist while the 'toxic beast' continues to be fed

As the people of Mosul mark a year of the horror that is living under Islamic State (Isis), there exists a brutal context — as with other terrorist groups remaining and expanding in conflicts from Libya to Yemen — that tragically will remain the same for the near term. In understanding and defining the tragic milieu, there are a few things to consider.

IS and other Sunni terrorist groups share a common trait

Though IS, al-Qaeda core, al-Qaeda in Yemen and North Africa, Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria, Boko Haram in north-east Nigeria, and al-Shabaab in the Horn of Africa all have various — and, at times, overlapping — causes and motivations, they were created from and shaped by mostly local or regional circumstances. Thus, in a more nuanced examination, they exhibit more contrasts than comparisons.

The toxic dogma that spawned this mutant form of violent extremism has gained size and strength in recent years

But they share an identical trait that persists: ideology. This ideology is the cancer — IS, for example, is simply a manifestation of the disease — in regions it has infected. The toxic dogma that spawned this mutant form of violent extremism has gained size and strength in recent years, whereby in the post 9/11 era, violent extremist groups fill the void of bad or failed governance and ensuing chaos.

They will continue to be opportunistic tumours attacking weak tissue. Extreme religious zeal may be a genuine motivator for some members and group leaders but it bumps squarely against the quest for power, control and wealth.

Their religious rituals sit right next to their criminal enterprises, which include extortion, drug trafficking, protection rackets, hostages for ransom, trafficking in persons and illicit sale of antiquities and other stolen goods.

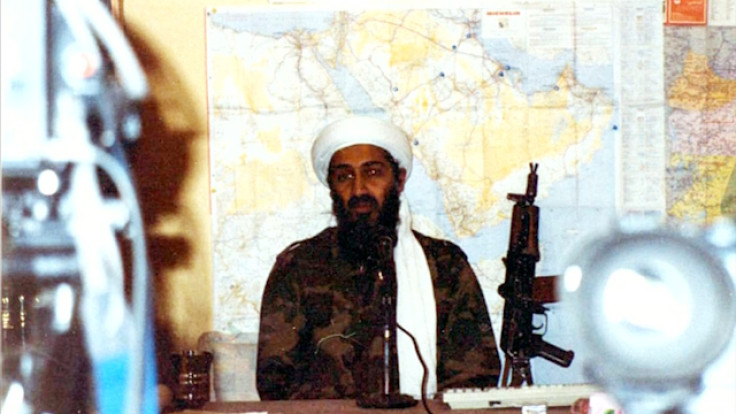

It's not as much the group as the Bin Laden-like ideology

Sometimes referred to as the salaf — or those who emulate the companions of the Prophet Muhammad — it evolved from Islam's most well-known "roots" theologian Ibn Taymiyyah in the 13<sup>th or 14<sup>th century.

It reared its violent and modern head in the 1950s and 1960s via the influence of Egyptian religious firebrands Sayyid Qutb and Muhammad Abdul Salam al-Faraj, who greatly influenced Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden deftly co-opted their philosophical underpinnings to shape his own version of political Sunni Islam, where abject violence is not only a remedy but the only solution.

At its foundation is the narrowest form of religious and behavioural absolutism that incubates and nurtures an extremely intolerant ethos known as takfir. Takfiris persistently accuse all who are not them of kufr (unbeliever) and, even worse, proclaim murtad (apostate), often uttered by self-appointed judge-jury-executioners of IS before they kill other Muslims, particularly Shia.

The appalling delusion of supporting terrorist groups

Some Middle East regimes have a long and sordid record of seeking to leverage, for foreign and domestic policy goals, violent extremist groups. Moreover, these state actors often create permissive environments for their own citizens to raise and traffic funds for these groups.

Tragically, they continue to believe terrorist organisations will do their bidding by proxy and that it will produce positive results. But the record is clear on this: once you let the evil takfiri genie out of the bottle, you cannot and will not control it.

Modern history's evidence is replete and includes the aftermath of the Afghan-Soviet war of 1979 to 1989, Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s, the Yemeni civil war in 1994, and presently Libya, Syria, Iraq and Yemen again.

As countries on both sides of the Arabian/Persian Gulf back their favoured violent gangs and networks, they in turn feed the beast of chronic conflict and strengthen the magnetic force attracting foreign fighters.

Nothing changes until local and regional conditions change

The persistent terror situations and sectarian conflicts will remain as long as local conditions are unchanged. Throughout north and Sahel Africa to the Levant and Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan and Pakistan, it's the political, governance, security, economic and education systems that desperately need transformation.

Feeding the beast are any combination — and not a complete list — of ingredients that stir the toxic stew

IS's otherworldly extremist ideals do not resonate so much as the lack of alternatives for those in the areas where its influence is spreading.

But through all that, whether it's the anger authoritarian regimes engender at home, or the reign and collapse of dictators in Iraq, Libya and Yemen, the outcomes have consistently mutated into a chaotic rump state and resultant breeding ground for extremist violence.

Feeding the beast are any combination — and not a complete list — of ingredients that stir the toxic stew: generations of civil-service corruption, personality cults, institutional paucity, woeful education systems, reaction to regime violence, dearth of liberal economies and no hint of opportunity where elites rule ruthlessly and merit is not considered.

They know the turf but instant gratification alliances are fleeting

With the passing of one year since IS captured Mosul, it should not be revelatory that the group's leadership — mostly former Saddam military, intelligence and Ba'athist officials — knew the area, leveraged tribal ties, and exploited local disdain and fear of the Shia rulers of Baghdad and their Iranian allies.

IS's military council knew there was an extreme deficit of leadership in the Iraqi army and police force and counted — correctly — on their quick collapse. It should also come as no surprise that the influential al-Jumayli tribe in Anbar Province threw in with IS recently.

Though it will remain argumentative whether the shaykhs in the Sunni heartland really believe "in the way of the [Islamic State] caliphate", it's self-evident they see a better alternative — and a more potent vexing of Baghdad, Tehran, and the Shia militias of the Popular Resistance Committee — than the appalling former Nouri al-Maliki regime and the present Haider al-Abadi government.

However, count the days until IS's brutality and draconian, if not foreign and bizarre, edicts wear out their welcome and the Anbar Sunnis once again fight against it.

Robert McFadden is a senior vice president at the Soufan Group, which provides strategic security intelligence services to governments and multinational organisations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.