Janusiscus: 415 million-year-old two-faced fish shows humans are less evolved than sharks

A 415 million-year-old fossil has shown that sharks are more advanced than humans, having shed their bony bodies millions of years ago.

The fossil of a fish skull was discovered near the Sida River in Siberia in 1972. It was noticed in an online catalogue by Imperial College scientist Martin Brazeau, who decided to study the specimen further with modern technology.

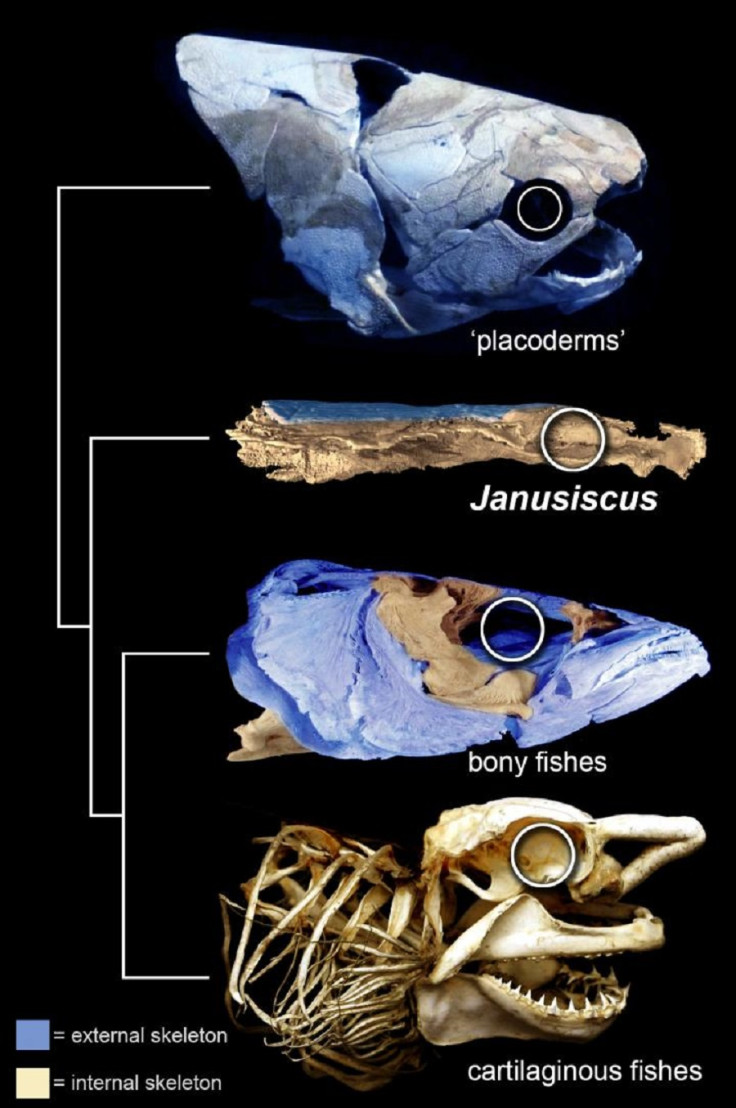

Using X-ray CT scans, the creature was found to have the external features of the osteichthyans – a group characterised as bony fish that once included humans – but the brain structure of cartilaginous fishes (chondrichthyans) – which includes sharks, rays and skates.

As a result, the two-faced-creature was named Janusiscus after the double-faced Roman god Janus.

Published in the journal Nature, the scientists say the find provides further evidence supporting the theory that sharks are not a primitive species.

Last April, a newly-discovered shark-like fish suggested that modern sharks are quite advanced in evolutionary terms. The 325 million-year-old fossil had arches in its jaws unlike anything seen in a modern shark – instead it appeared like that of a bony fish, suggesting modern sharks are very specialised and not at all primitive.

Matt Friedman of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences, author of the latest study, said Janusiscus provides a "glimpse of the Age of Fishes", where modern groups of vertebrates were starting to take off.

Sam Giles, first author of the report, said the fossil turns the view of sharks as primitive "on its head". Previously, it was believed that bony fish would have evolved from a cartilaginous common ancestor, meaning sharks were less evolved than bony fish and, as a result, humans.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, she said: "The idea was that the last common ancestor of the two groups would not have had bone, then the bony fish evolved and went on to be more sophisticated.

"This animal shows the last common ancestor of the two groups would have had bone, so if anything, the cartilaginous fishes have become more specialist in losing that bone, whereas the bony fishes retained it from their ancestors."

Friedman said: "This mix of features, some reminiscent of bony fishes and others cartilaginous fishes, suggests that humans may have just as many features that you might call 'primitive' as sharks."

"Losing your bony skeleton sounds like a pretty extreme adaptation, but with remarkable discoveries from China, Janusiscus strongly suggests that the ancient ancestors of modern sharks and their kin started out just as 'bony' as our own ancestors."

Giles said there is a misconception that sharks "haven't really done anything in 400 million years", but evidence is increasingly pointing to the opposite: "If you have a look at the latest fossil and even the living things, they've developed a huge range of ways of living in the sea and adapting to their environment, so they're no more unevolved or primitive than we are.

"There's a huge range of them and just because they've stayed in the sea and not moved to land does not mean that they're primitive in any way.

"You could say that the lineage leading to humans could be viewed as more primitive than cartilaginous fishes ... Both groups are very well evolved. Both have taken the body plan of their last common ancestor and specialised it in a multitude of different ways to suit their own environment. [But] sharks lost their skeleton and we kept it from our ancestors."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.