Fukushima images: Six years after the tsunami, life is returning to the ghost towns of northern Japan

The evacuation order for several towns in the shadow of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is set to be lifted on 31 March.

On 11 March 2011, a massive earthquake and tsunami devastated the seaside town of Namie. Once home to more than 20,000 people, it became a ghost town,. But now – six years after the disaster that destroyed wide swathes of northern Japan – signs of life are beginning to return.

The evacuation order for Namie and three other towns in the area is set to be lifted on 31 March, but many people are understandably reluctant to return. Roads and houses have yet to be fixed and huge black bags full of radiation-contaminated soil are a common sight.

In a recent survey, only 18 per cent of Namie evacuees said they want to return. More than half said they won't be going back, citing concerns over radiation and the safety of the nuclear plant, which is being dismantled in an operation expected to last 40 years. About 30 per cent remain undecided. More than three-quarters of those aged 29 or under have said they don't want to come back, so older people could form the bulk of the town's population.

On 3 March 2011, a massive earthquake hit northern Japan, triggering a 10-metre (33-feet) high wave that swept away everything in its path, killing nearly 20,000 people and turning entire towns into matchwood. The tsunami sparked the world's worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. Meltdowns in three reactors at the plant spewed radiation over a wide area, contaminating water, food and air. More than 160,000 people were evacuated from nearby towns.

Some former residents of Namie have already returned. Munehiro Asada, who owns a timber factory in the town, says he is keen to continue life in Namie even though profits after the disaster have dropped significantly. "Sales barely reach a tenth of what they used to be," he said. "But running the factory is my priority. If no one returns, the town will just disappear."

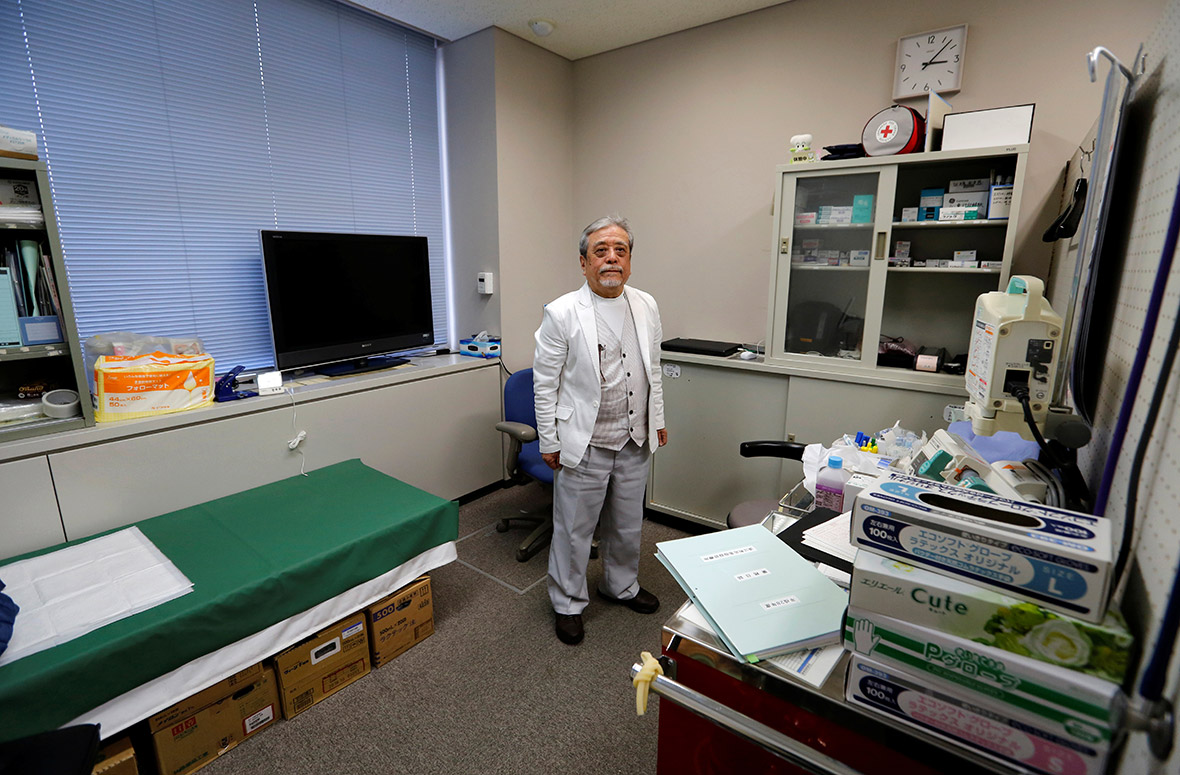

A hospital is due to open later this month, staffed with one full-time and several part-time doctors. Reconstruction efforts may create some jobs. The town's mayor, Tamotsu Baba, hopes to draw research and robotics firms. "Six long years have passed. If the evacuation is prolonged further, people's hearts will snap," he said. "The town could go completely out of existence."

Once a month, Ukedo primary school principal Chieko Oyama visits the tsunami-wrecked facility. Inside the classrooms are clocks that stopped around the time the tsunami hit the school. Oyama, who currently lives in Nihonmatsu city, two hours' drive away from Namie, visits to check up on her school and take photos, in the hopes of persuading officials to preserve it in its current state instead of mowing it down.

"I want children to see the intensity, strength, and the terror of tsunamis, but I also want them to visit the school and see for themselves what we had to overcome to be where we are now," Oyama told Reuters, adding that she has yet to decide whether to move back.

The absence of people has been a blessing for wildlife in the area. Shoichiro Sakamoto, 69, has an unusual job: hunting wild boars encroaching on residential areas in the nearby town of Tomioka. His 13-man squad catches the animals in a trap before finishing them off with air rifles.

"Wild boars in this town are not scared of people these days," he said. "They stare squarely at us as if saying, 'What in the world are you doing?' It's like our town has fallen under wild boars' control."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.