Leukaemia's Achilles heel - Targeting two proteins helps kill resistant cancer cells

Two signalling proteins that help cancer cells resist chemotherapy could be targeted by treatments.

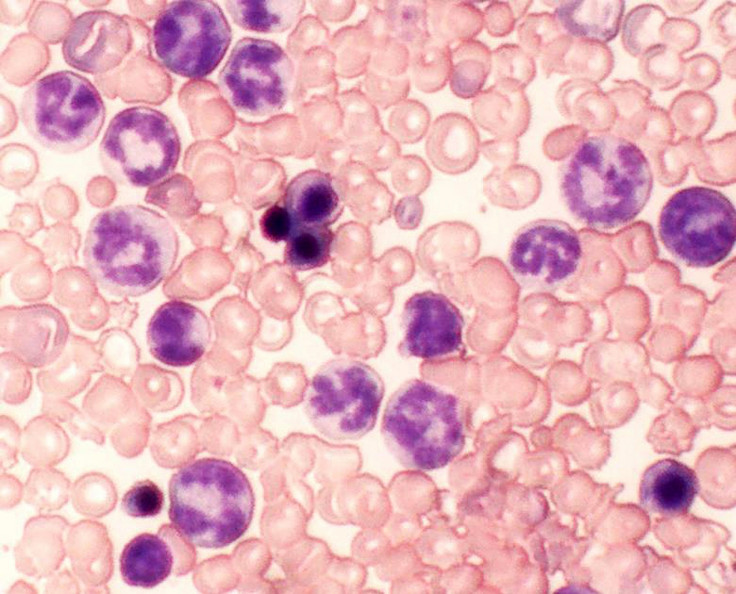

Scientists have discovered two signalling proteins in cancer cells, which make them resistant to chemotherapy treatment. Their findings could pave the way for the development of more effective treatments of certain types of cancers, chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) in particular.

Different types of blood and solid tumour cancers are driven by chemical messengers (enzymes) known as tyrosine kinases. These include CML, but also certain types of lung cancers as well as HER2-driven breast cancer.

These cancers can be treated with a class of chemotherapy medication known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). These drugs work by blocking tyrosine kinases, which otherwise help send growth signal to cells – thus promoting cancer cells growth and division.

The problem is that therapeutic benefits of TKIs are temporary because some cancer cells – residual disease cells – survive. Patients thus often relapse after chemotherapy.

"Kinases drive quite a large number of cancers, and in CML a genetic fault responsible for excessive kinase activity is present in almost all patients. The hope was that using TKIs would cure them by directly targeting the cause of their cancer. Unfortunately, even though some patients have had good response, the drugs fail to get rid of all cancer cells", Dr Justine Alford, senior science information officer at Cancer Research UK told IBTimes UK.

In their study published in Nature Medicine, the scientists have taken the example of CML to find out why some of these cells cannot be killed.

Two proteins to target

The team worked with a mouse model of chronic myeloid leukaemia, and analysed human CML cells donated by patients.

In these chemotherapy-resistant cells, the researchers observed extremely high levels of two signalling proteins called c-FOS and DUSP1. Using the mouse model, they showed that tyrosine kinase combined with other growth factor proteins to dramatically raise these levels of c-FOS and DUSP1.

"These two proteins were known before, but no one had looked at what happened to them in oncogenic conditions. We don't yet have a full understanding of how they work but we think that DUSP1 and c-FOS support the survival of cancer stem cells by increasing the toxic threshold needed to kill them. These proteins both protect cancerous cells from cell death and give their proliferation a boost. This means conventional chemotherapy struggles eliminate them", lead author Mohammad Azam, from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, told IBTimes UK.

In the second part of their study, the scientists decided to find what therapies could target the two proteins. They tested different treatment combinations on mouse models of CML, human CML cells, and mice transplanted with human leukaemia cells, to see which would be more effective to treat the disease.

They compared three types of treatment: chemotherapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitor only, treatment with two molecular inhibitors of c-FOS and DUSP1 only, and a combination of chemotherapy and inhibitors of c-FOS and DUSP1.

This last one was the most effective. Taken during one month, it treated successfully 90% of mice with CML – they had with no signs of residual disease cells.

"We think that within the next five years our data will change the way people think about cancer development and targeted therapy. This study identifies a potential Achilles heel of kinase-driven cancers. One of the things that we are looking into now is making a drug combining both a c-FOS inhibitor and a DUSP1 inhibitor", Azam said.

This represents an important step in understanding why some CML cells are resistant to chemotherapy. However, more research in animal models and humans will be needed before these therapies can be used in patients.

"Although these findings are robust, more research will be needed to back them up. We don't know yet whether they will be applicable to humans and clinical trials will have to be held. It's possible that giving humans three drugs will be quite toxic, we need to determine if such therapy will be safe and effective before these experimental drugs can reach patients", Alford concluded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.