Optogenetics: Lost memories restored in mice with amnesia through blue light

Memories lost through amnesia have been retrieved by scientists by activating brain cells using light.

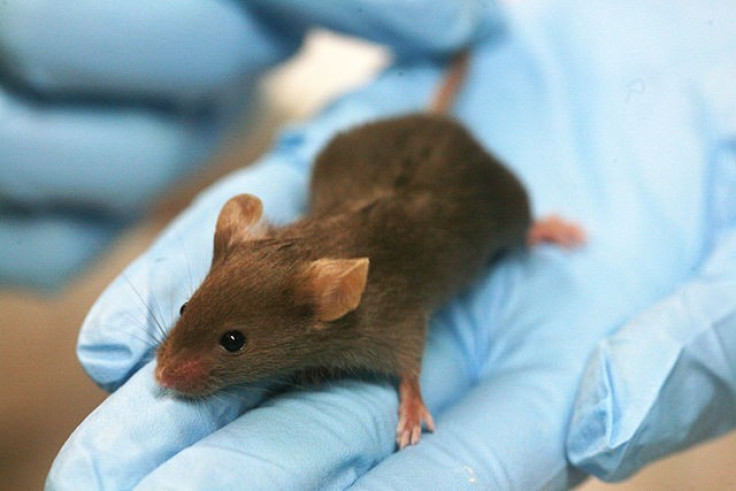

Scientists from Riken-MIT were able to reactivate memories in mice through a technology called optogenetics.

The study, published in the journal Science, set out to discover how stable memories are formed in the brain – and if memories that are not stored properly could be recalled. Study leader explained: "Brain researchers have been divided for decades on whether amnesia is caused by an impairment in the storage of a memory, or in its recall."

The nature of amnesia has been the subject of debate for decades. Some have said it is caused by damage to specific brain cells, meaning the memory cannot be stored. Others believe access to the stored memory is blocked in amnesia.

"The majority of researchers have favoured the storage theory, but we have shown in this paper that this majority theory is probably wrong," Tonegawa says. "Amnesia is a problem of retrieval impairment."

In 2010, the group used optogenetics, where proteins are added to neurons so they can be activated with light, to show how there is a population of neurons in the brain that are activated during the process of acquiring a memory. They found it exists in the hippocampus.

In the latest study, scientists first trained the mice to associate a mild foot shock with a specific environment, creating a "freezing" behaviour. Eventually, the mice froze when placed in the chamber even without being shocked.

The neurons activated during the memory formation were genetically labelled so scientists could reactive them. Some of the mice were then given a chemical that prevents increase in synaptic strength, which is important to memory encoding, creating retrograde amnesia.

When these mice re-entered the chamber, they did not freeze because they could not recall the memory of being shocked.

Researchers then used optogenetics to selectively activate the neurons that had been labelled during the training in the chamber. When the memories were reactivated, the mice froze – showing they remembered the acquired memory.

The scientists believe their findings suggest there are different processes that control memory encoding and recall.

"Our conclusion is that in retrograde amnesia, past memories may not be erased, but could simply be lost and inaccessible for recall," Tonegawa said. "These findings provide striking insight into the fleeting nature of memories, and will stimulate future research on the biology of memory and its clinical restoration."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.