Mass grave containing up to 150 'unidentified' bodies found in Morelos, Central Mexico

A Mexican state human rights agency has begun an investigation into why up to 150 bodies of crime victims were dumped into pits in an area rife with kidnappings and executions. Investigators have discovered the bodies, some wrapped in plastic, in unmarked graves in Morelos, Central Mexico.

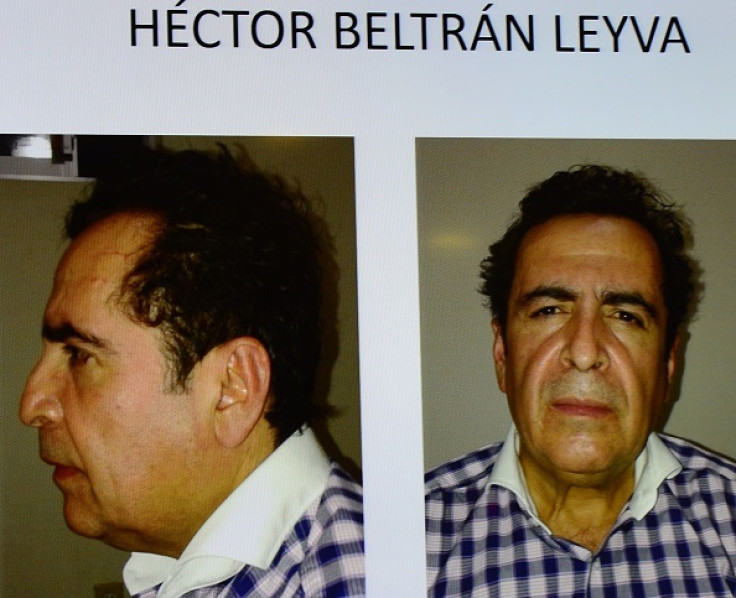

The area has been plagued by violence since the 1990s, when the Juarez Cartel and the Beltran Leyva Cartel began a long-running feud which was further complicated by the emergence of other drug gangs. Several local high-ranking state officials have been accused aiding traffickers in the state.

One of the reasons they may have been relocated to the pits may have been to clean out the state morgue, but some of the bodies lack identifying case numbers – posing questions as to how they met their end. Other theories allude to haphazard police work or foul play at the behest of narcotics kingpins in the small, indigenous community, infamous for having one of the highest kidnapping rates in the country.

The officials are being investigated for dereliction of duty and violation of laws covering the burial of corpses, prosecutor Javier Perez, said in a statement on Friday. He did not specify how many officials were being investigated, or how long the "unauthorised" mass grave, in a town east of the city of Cuernavaca, is believed to have been in operation.

Investigators visited the town on Friday, 6 November, but the long-running scandal was revealed in 2013 when the family of murdered kidnap victim, Oliver Wenceslao, were told that his body had been sent to a mass grave after police officers asked to keep the body for further testing.

A judge ordered the state prosecutors' office to exhume Wenceslao's body in September this year and return it to his family. But when investigators began digging they found up to 150 bodies in a deep pit.

"The bad thing is that, during this exhumation, they found several things wrong," said Rafael Idiaquez, spokesman for the Morelos state human rights commission, in the el Nuevo Herald. Ordinarily Mexican morgues prepare bodies for common graves by placing them in plastic bags.

Within these bags is a case file number in an empty plastic bottle to avoid contamination. But Mr Idiaquez revealed the bodies lacked this crucial information. He said: "There are bodies that don't have any case file number.

"We don't know why they are there, if they were executed, if they have relatives, if any investigation was ever done in their cases." He added several people have contacted the commission, saying they fear their relatives may have been buried in the mass grave.

The Morelos state prosecutors' office claimed that all the corpses had a case file in which their fingerprints, dental profiles and genetic profiles were recorded. But, it seems, the only way to match records would be by using genetic testing on each set of remains.

In July this year, Mexican authorities discovered some 60 mass graves and 129 bodies while they were searching for the corpses of 43 students who went missing from Iguala city, Guerrero state, in September 2014.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.