Massive frozen methane domes at the bottom of Arctic sea could soon explode

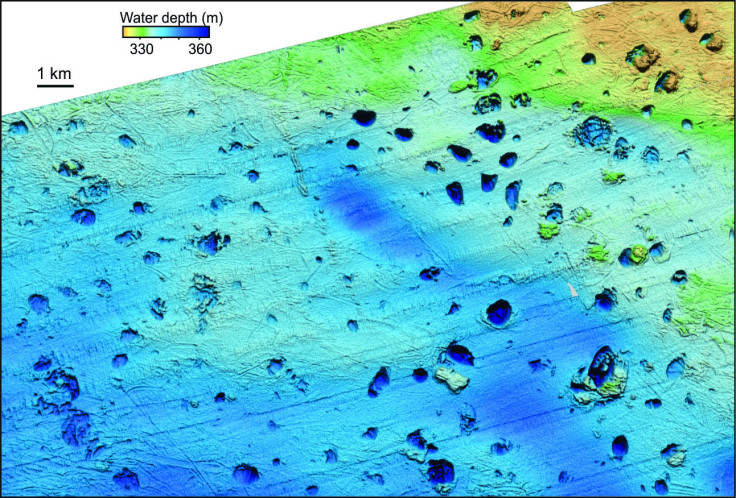

The dome field was found near the huge Barents Sea craters.

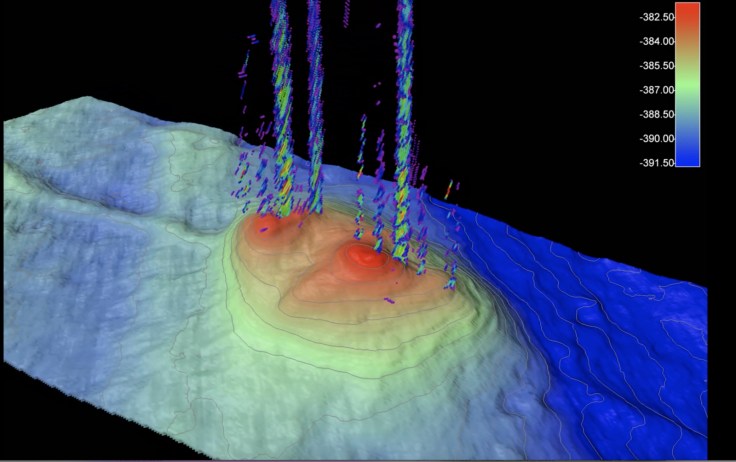

On the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean, a field of huge frozen methane domes has caught the attention of scientists as they believe these structures could signal upcoming methane expulsions that have previously created massive craters in the area.

In a study recently published in the journal Science, researchers described some of these large craters found in the vicinity of the dome field, and detailed how they formed when the ice sheet retreated from the Barents Sea during the deglaciation some 12,000 years ago.

Now, in a paper published in PNAS, they describe the evolution of the domes – some of which are 500 metres wide.

The scientists suggest that they are the present-day analogue to what they think preceded the craters on the floor of the Barents Sea.

Gas hydrate reservoirs

The authors combined geophysical observations and models of shallow Arctic Ocean gas hydrate reservoirs to study the processes that led to the episodic release of methane over the last 30,000 years.

They identified distinct phases of accumulation of methane under the glaciers and subsequent release of pressure when the ice sheet retreated, which led to the formation of the seafloor domes.

"We go on expeditions several times a year and are closely surveying this area. These domes are mounds of hydrates that are very sensitive to pressure and temperature," lead author Pavel Serov, PhD candidate at CAGE at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, told IBTimes UK.

Hydrates are stable in low temperatures and under high pressure. At the moment, the pressure of 390m of water above is keeping them stabilised. But the methane is bubbling from these domes and higher sea temperatures could in the future lead to significant expulsion of methane.

"If the temperature rose just a little, they could collapse and methane could escape. The temperature in the ocean has not reached this critical level yet, but it's quite close. We believe that one step before the craters are created, you get these domes," Serov added.

If these domes collapsed entirely and abruptly, releasing methane into the ocean, he thinks the overall impact on global warming wouldn't be significant as there are only a few of them.

However, closely monitoring the evolution of the dome field is crucial to understand the ongoing processes of methane sequestration and release in the Arctic ocean. During future expeditions, the scientists would like to drill the domes to find out more about their formation and about the frozen methane trapped within.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.