Meet the Hurricane Katrina survivor who now rescues migrants in the Mediterranean sea

It is difficult to work out the connection between a millionaire from Louisiana and the thousands of refugees making the perilous journey across the Mediterranean to Europe. But Christopher Catrambone is no stranger to displacement and disaster.

After losing his home to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, he moved to Europe to further his blooming business, Tangiers, which provides insurance to journalists, NGOs and contractors in conflict zones. After witnessing the plight of migrants crossing the Mediterranean first-hand during a luxury cruise, he channelled his earnings into launching a rescue mission.

How can we be here enjoying our summer holiday in the gorgeous Mediterranean water, while at the same time, people are drowning?

In June 2013, Catrambone and his wife Regina and daughter Maria Luisa chartered a yacht for a three-week trip to Tunisia. Departing from their home on the island of Malta, the cruise would take them along the sun-soaked idyll of the Sicilian coast. They planned to stop on popular tourist island Lampedusa, situated between Sicily and Tunisia, which is a landing point for migrants trying to enter Europe.

As the Catrambones sailed away from the harbour, Regina spotted a thick coat floating in the water – a seemingly out-of-place object in the height of summer. "That jacket, we were told, likely belonged to a migrant that had drowned," Catrambone says. "It was that duality that made us think, how can we be here enjoying our summer holiday in the gorgeous Mediterranean water, while at the same time, people are drowning?"

The family had witnessed an escalating crisis. Three months after they returned from their trip, a boat carrying migrants from Libya to Italy sank off the coast of Lampedusa killing 360 people – the majority Eritreans, Somalians and Ghanaians. Now, the flow of desperate refugees fleeing North Africa with hopes of reaching Europe in rickety and overcrowded boats is significantly higher. More than 2,000 people are believed to have died trying to cross the world's most dangerous migrant route so far in 2015.

Dispelling the 'globalisation of indifference'

Seeing the coat in the water was the push to take direct action in the form of a rescue operation. "Pope Francis was visiting Lampedusa after a boat full of migrants had died. He talked about the globalisation of indifference and we agreed with his sentiments exactly and decided to act where we could help," Catrambone says. "At that time, there weren't enough coastguard assets at sea to conduct search and rescue, so we felt we found a good place to start."

The couple dug deep into their pockets to fund a 40m-long ship, the Phoenix, which is equipped with dinghies and drones used to find and help migrants in distress trying to enter Europe across the Mediterranean.

After a boat is spotted, we alert the coastguards whom have ultimate decision-making power at seas

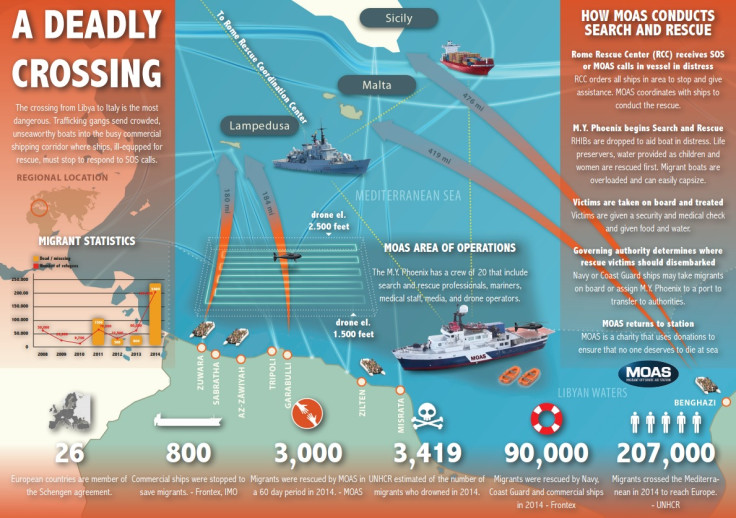

They called the project the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, which is based in Malta and carries an experienced team of rescuers and paramedics led by Martin Xuereb, Malta's former chief of defence. It has it has saved over 9,300 lives so far.

"A typical day consists of launching our drones to locate vessels in distress. After a boat is spotted, we alert the coastguards whom have ultimate decision-making power at seas. We are then directed to either intercept the boat or to assist other vessels with taking migrants on board using our two rigid-inflatable boats," Catrambone says.

Migrants are then given medical treatment, food and water, before being taken to dry land or moved to another coastguard vessel. "I have been a member of the team for two years now and have participated in many operations, as have my wife and daughter," he says.

In the past two decades, more than 20,000 men, women and children are estimated to have lost their lives while trying to cross the Mediterranean in search of a better life. On 5 August, around 400 people were reported to be rescued when a fishing boat carrying 600 migrants sank of Libya. In one of the worst wrecks, a boat with around 800 people overturned in the same stretch of water in April 2014. Just 28 survivors were recovered, including two alleged smugglers.

According to the International Organisation of Migration, 75% of all migrant deaths in 2014 occurred in the Med – one of the busiest seaways in the world, as well as a dangerous sea frontier for migrants and asylum seekers.

Displaced by Hurricane Katrina

Catrambone's dedication to helping migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean is one deep-rooted in his heritage, as the descendant of Italian migrants who sought a better life in the United States. Since graduating from McNeese State University in his hometown of Lake Charles, Louisiana, he has also worked in some of the most unstable regions in the world, such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Israel when it was being targeted by rockets from Hezbollah in Lebanon. He has also worked on some of the most violent housing projects in New Orleans.

Catrambone has also lived through devastation, after a category five hurricane swept away his home in 2005. "I was based out of New Orleans at the time of the hurricane, so I was out of town working in the Bahamas when it hit," he says, as the 10th anniversary of the disaster nears. He was based in Nassau, Bahamas – which was hit by Katrina first as a tropical storm, before it turned into a hurricane and made landfall in Louisiana.

"Technically Katrina did a double-take on me. I tried to return to new Orleans but flights were cancelled and roads were closed into the city, so I ended up finding refuge in Saint Thomas in the US Virgin Islands," he says. His home in the eastern Ninth Ward of New Orleans, which experienced catastrophic flooding, was destroyed.

"After discovering my house was condemned, I decided to stay in St Thomas and invited my two friends, who were now displaced chefs from New Orleans, to join me to form a start-up Cajun eatery called Cajun Mary's Riverboat Lounge," Catrambone says. The group pooled their compensation money to fund the business. "It was our way of grieving after losing our home, our friends and our soulful city's culture."

His friend Simon Templer, one of the chefs who joined Catrambone in St Thomas, now works onboard the MOAS vessel Phoenix. "His still serving up the best Cajun cuisine, but now in the Med," he says.

By the age of 26, Catrambone's path was already varied, from his steamboat restaurant in the Virgin Islands to working at the US Congress and running a political campaign in his home state. In 2006, Catrambone took another direction and founded Tangiers, which provides insurance, services and intelligence to those working in conflict zones.

With his business growing rapidly, he moved to Reggio di Calabria in southern Italy where he met his business partner and wife Regina. They relocated to Malta for logistical reasons, as Tangier had expanded to reach more than 100 countries.

Since MOAS was set up two years ago, the 20-strong crew on board have been increasingly busy, as more and more people seek to reach Europe. In one 60-day period in 2014, the ship picked up around 3,000 migrants. Today, the Phoenix brought 202 refugees to Pozzallo, in the province of Ragusa in Sicily. Fifty people are feared to have died in a separate incident around 40km from the Libyan coast, when the dinghy they were sailing in deflated.

But with a head for business and a heart for philanthropy, Catrambone says he loves the adventure and challenge of tackling tough problems and helping people make it through difficult situations. Seeing the coat off floating off Lampedusa was the spark that ignited his desire to help those in crisis at sea.

"As the great grandson of Italian immigrants who came to the US, I'm very compassionate to the plight of people who seek a better life in order to escape disaster, persecution, conflict and famine," he says. "Hurricane Katrina taught me what it is like to be displaced and without a home."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.