Metal Gear Solid: Hideo Kojima's series shows us how sequels should be made

By all accounts Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain is a pretty fantastic video game. Not bad for a series with roots stretching back to the 1980s. Rather than resting on its laurels, MGS5 is a genuine evolution of the franchise that is likely to have its ideas liberated by developers around the world. It's a bittersweet irony that it could be Konami's last blockbuster release after the highly publicised split with Hideo Kojima.

Metal Gear and its creator are inextricably linked. Even its 1987 original on the MSX2 showed an exceptionally high level of ambition. Playing like a military-themed Legend of Zelda, it made the most of simple tools to deliver an unexpectedly immersive experience.

In 1998 Kojima returned to the series with Metal Gear Solid, and in doing so propelled the series into the stratosphere, making use of the new hardware's 3D rendering capabilities for new gameplay mechanics and dramatic cutscenes. Ambition and innovation quickly became Metal Gear Solid's trademarks.

Since MGS wrote the rulebook for 3D action games, most AAA franchises have followed in its footsteps. With every character-led release, the same lines are trotted out in interviews with developers about strong characters, strong narrative arcs, strong emotions and so on. David Cage has virtually made a career out of it.

What differentiates Metal Gear Solid is the way it flourishes where other franchises stutter – its sequels. Rather than simply refining its mechanics and escalating the plot, MGS never misses a chance to astound and surprise. For other big franchises like Halo and God of War, the difficult second game was more or less an overlong trailer for the third chapter - perhaps derived from the trilogy model that was all the rage in Hollywood back in the 2000s.

As development costs rise, so does the chance of a homogenised end product. When Assassin's Creed was released in 2007, it was a hugely ambitious title with an interesting framing device. Eight years on, it is infamous for coming up with the Ubisoft blueprint: open worlds with an unlockable map filled with missions re-skinned every year, across multiple series and genres. Assassin's Creed's once stark and unique mythology was quickly written into a corner it has yet to escape from.

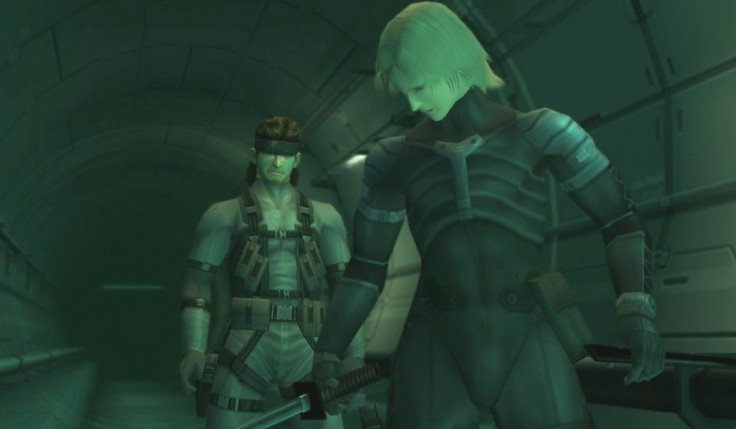

With MGS2: Sons Of Liberty, Kojima pulled the rug from under everyone and defied all expectations by bringing in an entirely new protagonist, Raiden, while managing to avoid leaking this development in advance. It would be almost impossible to pull the same trick again in today's hyper-marketed, big-budget, low-risk gaming era. Following up an audacious success by throwing away its iconic protagonist is practically unthinkable now, especially for such a character-driven series.

With MGS 3: Snake Eater and 4: Guns Of The Patriots, Kojima further expanded on Metal Gear's mythos yet still delivered unexpected twists. You play as series villain Big Boss in Snake Eater's 60s-set prequel, then as Solid Snake once again in the narrative-heavy, loose-end-tying follow-up. This universe is inhabited by more than simple archetypes – there's a richness and complexity of character rarely seen in games. Every villain has clearly defined motivations and philosophy instead of being a vague mass whose sole purpose is to roar at the player and be defeated.

With every new entry in a big franchise, there's a pressure to add more content. New features are piled on top of old ones without much thought. Each edition of Grand Theft Auto since its genre-defining third entry has introduced new features, but these largely feel like distractions rather than being fully integrated into the core experience. In Metal Gear, each feature adds a whole new dimension. When first-person aiming was introduced to MGS2, rather than just being able to line up shots better you could intimidate soldiers into laying down their arms. MGS3 relied heavily on its unique camouflage system and MGS4 brought in an ally, adding in an element of teamwork.

Now – in MGS5: The Phantom Pain – the series has embraced an open world system. There was a sneak preview of how it would work in Ground Zeroes – a relatively small playground but one that could be approached in just about any way you wanted. On its own it made for a full, satisfying experience but is only just a taster for what can be done in The Phantom Pain. It's ironic that Kojima's last game at Konami is so forward thinking.

The upcoming entries of Halo and Uncharted are sure to be solid games in their own right and will no doubt satisfy fans of those respective franchises. But tonally and mechanically, they still remain close to their origins. Striking the balance between progress and retaining the feel of the original in a sequel is tricky, so the logical thing is just to do more of the same – especially with the demands of a quick development turnaround.

An auteur-style approach just isn't compatible with annual updates. It's been 7 years since the last numbered Metal Gear release. That kind of development time is too costly for anything other than a guaranteed success. Perhaps there's no space for someone like Kojima in a time when two- or three-year development cycles are becoming the norm. Though The Phantom Pain may not be the last we see of Kojima, it's hard to imagine anyone having the same long-lasting impact in the immediate future.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.