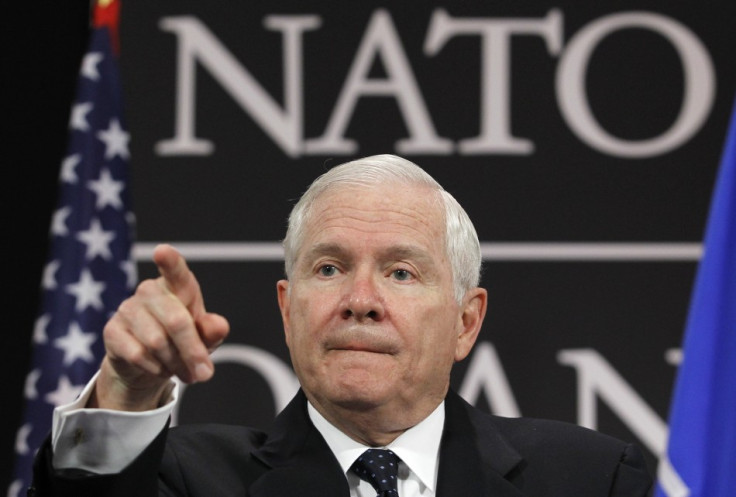

Nato could fade away, warns US Defense Secretary Robert Gates

Just as leaders from Nato member countries maintain that following the operation in Libya, Gaddafi's days in power are numbered, and as Nato officials this week insisted the operation was a success, US defence secretary, Robert Gates, today delivered a blistering attack on European defence complacency, declaring that Nato has "become a "two-tiered" alliance of those willing to wage war and those only interested in "talking and peacekeeping".

The blunt warning came rather at a surprising time in view of the organisation facing criticisms for its choice of stepping up its bombardments campaign on Tripoli, but the head of the Pentagon insisted that Washington's fading commitment to European security could spell the death of the 60-year-old alliance.

Besides, as Gates is due to retire in three-weeks, he made sure the audience understood his exasperation and frustration at the Alliance relying heavily on the U.S for financial backing and as he denounced European defence spending cuts, inefficiencies and botched planning, he also read the riot act to his European audience.

In recent years, Americans have lobbied strongly against European defence cuts as even after 9/11, defence spending declined by nearly 15% over the following decade.

Nato faced a "dim, if not dismal" future, consigned to "collective military irrelevance", Gates argued. In a staunch warning Gates warned that Nato was living on borrowed time and that a new young generation of US leaders could abandon the Alliance as the geopolitical map of the world is rapidly evolving and the divisions brought about by the cold war could be replaced by new ones.

"If current trends in the decline of European defence capabilities are not halted and reversed, future US political leaders - those for whom the cold war was not the formative experience that it was for me - may not consider the return on America's investment in Nato worth the cost."

During his speech the Defence secretary blasted the coalition forces lack of organisational and operational skills and planning before warning that the future of the Alliance could now depend on the "political and economic environment in the United States".

"The mightiest military alliance in history is only 11 weeks into an operation against a poorly armed regime in a sparsely populated country," Gates said of the Anglo-French led campaign in Libya. "Yet many allies are beginning to run short of munitions, requiring the US, once more, to make up the difference."

The US share of Nato military spending has soared to 75%, which in view of today's economic crisis cannot be overlooked. Gates made it clear that the US taxpayers would not stand for it much longer, while the US Congress and "the American body politic writ large" were prepared to rebel against spending "increasingly precious funds on behalf of nations apparently willing and eager for American taxpayers to assume the growing security burden left by reductions in European defence budgets".

Nato had degenerated into an alliance "between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of Nato membership but don't want to share the risks and the costs", Gates fumed.

This could be seen as a direct attack to many European countries, including France and the U.K, two countries at the forefront of the operation in Libya.

French president Nicholas Sarkozy insisted on France playing a leading role in the operation, probably in an attempt to reinforce the declining influence of the country on the international scene. Frustrated by its inability to respond rapidly to the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia, and to move away from the critics who denounced the close relationship between the Ben Ali regime and several important figure of the Sarkozy government, the President declared in March that France had "decided to assume its role, its role before history".

As Gates suggests it, the ticket to historical notoriety does however not come at a cheap price.

Noting that he was 20 years older than President Barack Obama, Gates also explained that Washington's security guarantees to Europe, embodied in the Nato alliance, were fading because of generational change.

"I am the last senior leader in the US government who is a product of the cold war," said the former head of the CIA. His peers' "emotional and historical attachment" to Nato was "ageing out".

"You have a lot of new members of Congress who are roughly old enough to be my children or grandchildren."

"The drift of the past 20 years can't continue," Gates said. "In the past, I've worried openly about Nato turning into a two-tiered alliance: between members who specialise in 'soft' humanitarian, development, peacekeeping, and talking tasks, and those conducting the "hard" combat missions ... This is no longer a hypothetical worry. We are there today. And it is unacceptable."

While in March, the 28 Nato members voted for the Libya mission, "less than half have participated," while, "Fewer than a third have been willing to participate in the strike mission" he said. "Frankly, many of those allies sitting on the sidelines do so not because they do not want to participate, but simply because they can't. The military capabilities simply aren't there."

Mr Gates' speech is by far one of the starkest warnings delivered by a US defence secretary and his message was clear: in the future, America may become tired of helping out Europe in its own backyard, especially since because of the new generational gap, for the US, old friendships might not be as relevant as they used to.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.