No more war: Colombia signs historic peace agreement with Farc guerrillas

Colombian president Santos and Farc leader Timochenko use pen made from a bullet to sign peace deal ending 52-year war that killed quarter of a million people.

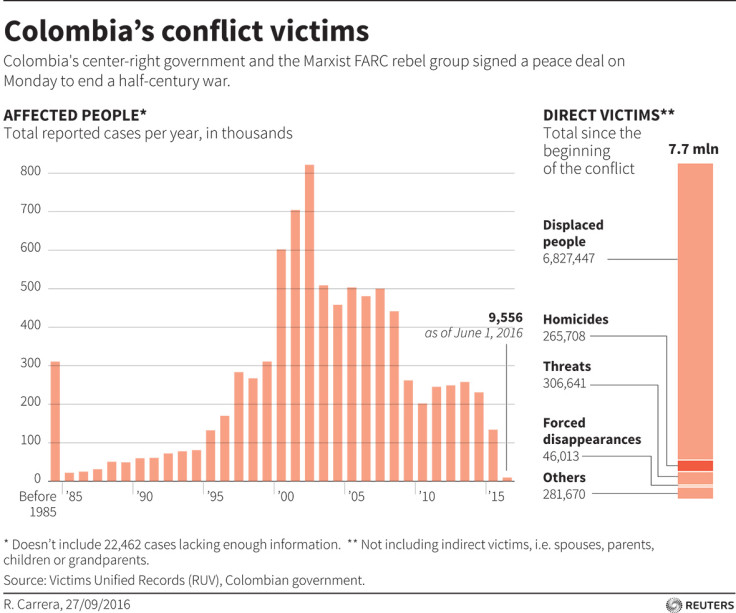

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and the Marxist rebel leader Rodrigo Londono, known as Timochenko, used a pen made from a bullet to sign a peace agreement on 27 September 2016, ending a war that has lasted for half a century and killed a quarter of a million people.

"Let no one doubt that we are going into politics without weapons," said Londono, a top commander of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), after the leftist rebel group formally signed a peace accord with the Colombian government.

Santos, who for years was the Farc's top military opponent, was equally emphatic that he would honor his promise to promote pluralism and open up Colombia's traditionally elite-driven political system. "As head of state of the fatherland we all love, I want to welcome you to democracy," he said. Earlier, he led the crowd in chants of "No more war! No more war! No more war!" AP reported.

After four years of peace talks in Cuba, Santos and Timochenko – the nom de guerre for 57-year-old revolutionary Rodrigo Londono – shook hands on Colombian soil for the first time. The emotional ceremony was carried out before a crowd of 2,500 foreign dignitaries and special guests, including UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Many in the audience had tears in their eyes, and shouts rose urging Santos and Timochenko to "Hug, hug, hug!" In the end, the two men just clasped hands and smiled effusively. Then Santos removed from his lapel a pin shaped like a white dove that he's been wearing for years and handed it over to his former adversary, who fastened it on his own shirt.

The ceremony mostly went off without a hitch although an apparently unexpected low flyover by military planes momentarily startled Londono, who resumed his speech with a joke: "This time they came to salute peace instead of unload bombs."

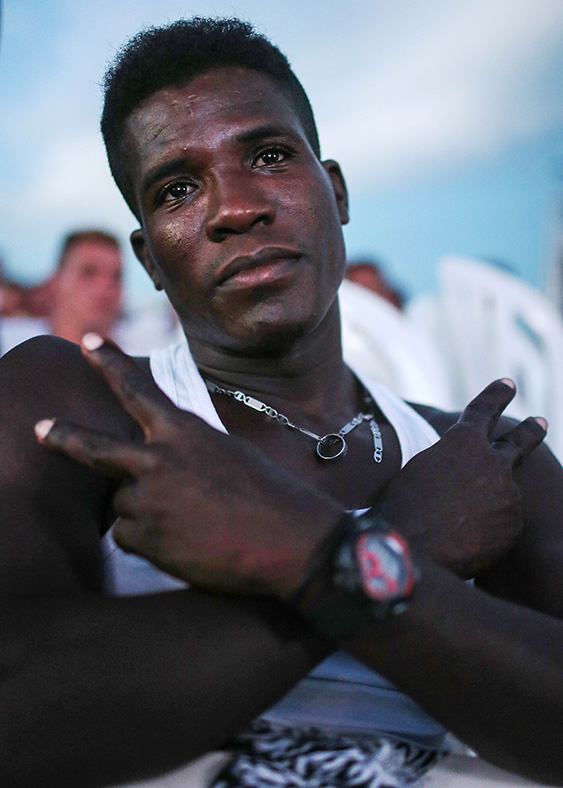

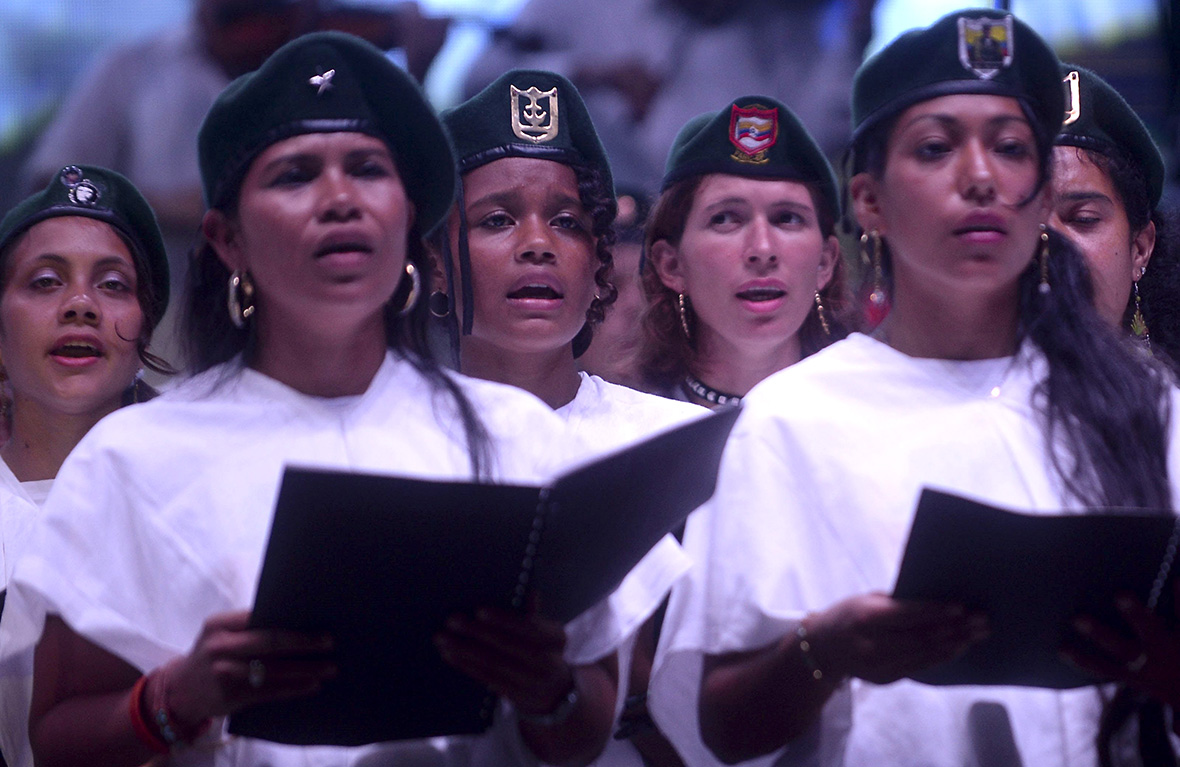

Around a thousand members of Farc gathered at their camp in Colombia´s southern Yari Plains to watch the ceremony on big screens. Applause erupted across the rows of men and women, as their leader signed the agreement. One former guerrilla told Reuters there was "fear but also lots of happiness and hope that all this can change".

The end of Latin America's longest-running war will turn the Farc guerrilla army into a political party fighting at the ballot box instead of the battlefield. The two sides have drafted an ambitious agenda to hasten the development of Colombia's long-neglected countryside and rid it of illegal coca crops that strengthened Farc — and some say morally corrupted it. Reconciliation will be a tough process that will require rebels and state actors who want to avoid jail to confess their war crimes committed during the 52-year conflict that saw brutalities on both sides.

European Union foreign policy coordinator Federica Mogherini said that with the signing of the peace agreement, the EU would suspend Farc from its list of terrorist organisations. Asked whether the US would follow suit, Kerry was less willing to commit but expressed a possible openness to similar action. "We clearly are ready to review and make judgments as the facts come in," he told reporters. "We don't want to leave people on the list if they don't belong."

Colombians will have the final say on endorsing or rejecting the accord in a referendum on 2 October. Opinion polls point to an almost-certain victory for the "yes" vote, but some analysts warn that a closer-than-expected finish or low voter turnout could bode poorly for the tough task the country faces in implementing the ambitious accord.

Farc, or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, began as a peasant revolt, became a big player in the cocaine trade and at its strongest had 20,000 fighters. Now its some 7,000 fighters must hand over their weapons to the United Nations within 180 days.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.