The original Brexit: How Britain's land link to Europe began its collapse 450,000 years ago

Giant waterfalls eroded the land bridge before a megaflood destroyed it completely.

The land bridge between Britain and Europe collapsed through a series of chance events spanning hundreds of thousands of years. A series of enormous waterfalls first weakened the land bridge, before a megaflood swept it away entirely.

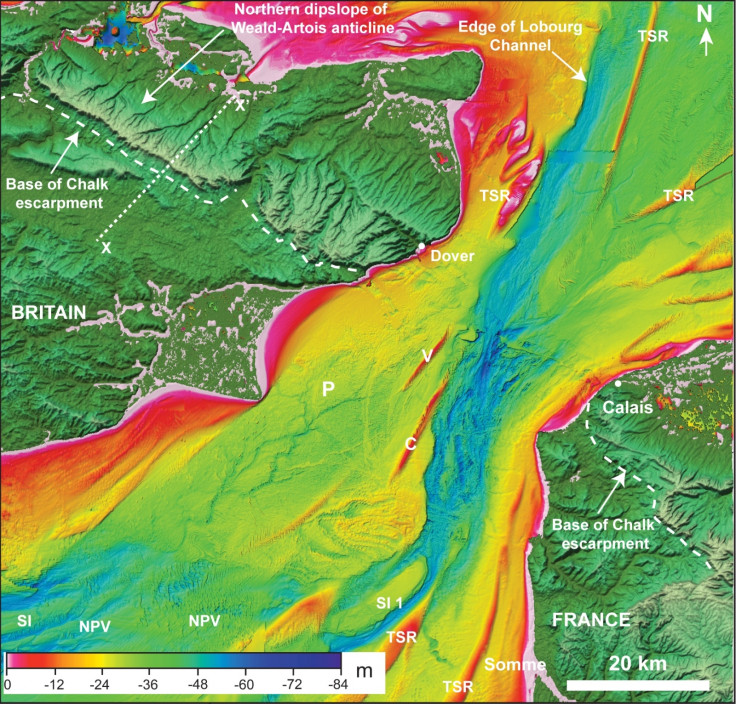

About 450,000 years ago, a bleak tundra bridge stretched for more than 30 kilometres between Dover in south-east England and Calais in north-west France. Two unrelated extreme flooding events related to separate periods of climate warming eroded this bridge, finds a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

"Were it not for this chance series of events, Britain would still be attached to Europe," study author Sanjeev Gupta of Imperial College London told IBTimes UK.

The bridge first began to weaken in the depths of an Ice Age 450,000 years ago. Sea levels were much lower than today, as much more of the world's water was locked up in glaciers.

"Based on the evidence that we've seen, we believe the Dover Strait 450,000 years ago would have been a huge rock ridge made of chalk joining Britain to France, looking more like the frozen tundra in Siberia than the green environment we know today," said Jenny Collier, also of Imperial College London and an author of the study.

"It would have been a cold world dotted with waterfalls plunging over the iconic white chalk escarpment that we see today in the White Cliffs of Dover."

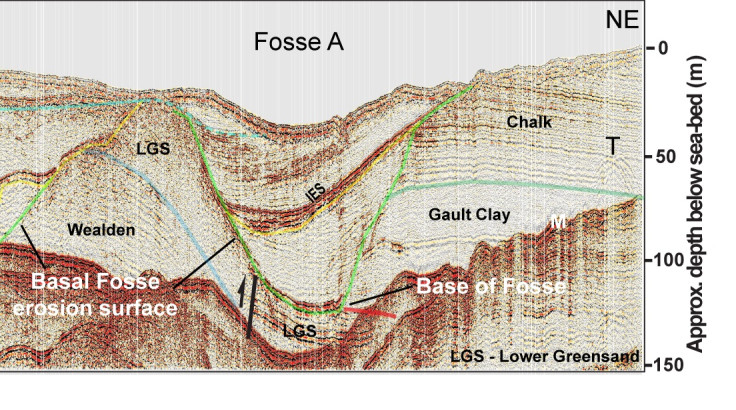

But when the British and Scandinavian ice sheets began to melt, the water formed a huge lake hundreds of kilometres across, bordered at the south by the land bridge. As the lake filled, it eventually began to overflow, creating at least seven enormous waterfalls that plunged over the bridge to the south and gouged out plunge holes that were up to 100 metres deep and kilometres across.

These plunge pools were then filled up with sediment and the bridge – although weakened by the waterfalls – remained in place for another couple of hundred thousand years. Then about 180,000 years ago, another period of melting led to the formation of a different lake putting pressure on the land bridge. This was the last straw, with a megaflood boring straight through the partially eroded bridge to form the English Channel.

Bathymetry data to analyse the lay of the sea floor still shows traces of this huge natural event.

"What you then see in the bathymetry data, you can see a major valley – 10 km wide – running through were the land bridge went. It cuts about 20m deep into bedrock," Gupta said.

"What's interesting about this is that it shows many features of erosion by high-magnitude flood. It slices through the plunge holes, cutting through the sediment in them so we can tell this event must have happened much later."

The combination of these two events, spaced hundreds of thousands of years apart, set the conditions to allow Britain to become an island. This took many more years after the megaflood, as conditions were still cold and the seas had yet to rise to present-day levels.

"But if it weren't for these two events, Britain and France would have a land border above sea level," said Gupta.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.