Alien object 'Oumuamua is covered in a strange organic coat created by cosmic rays

More details revealed about the first object ever detected in our own solar system to have originated from interstellar space.

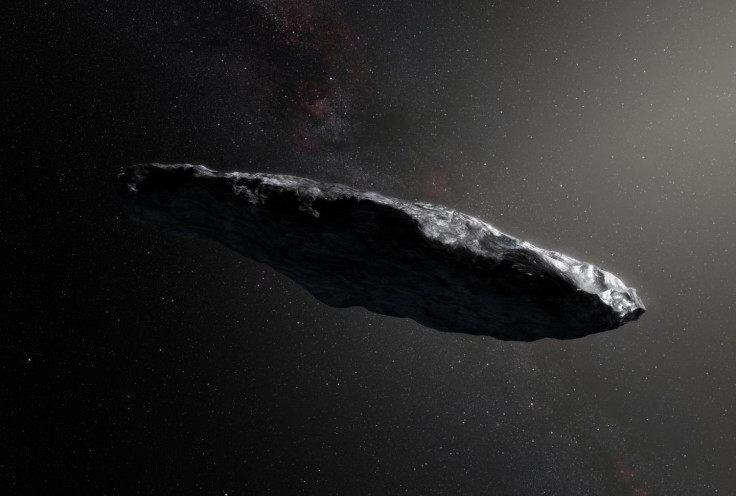

In October, astronomers made an unprecedented discovery when they spotted a strange, incredibly fast-moving object hurtling through the solar system, unlike anything that had ever been seen before

'Oumuamua, as it has been named, turned out to be the first object ever detected in our own solar system to have originated from interstellar space. Since then, scientists have rushed to learn more about it before it moves too far away to be studied in detail.

While initial scans have found little evidence that 'Oumuamua – a Hawaiian word meaning a "messenger from afar" – is the product of an alien civilisation, as some have suggested, new research, led by scientists from Queen's University Belfast, is beginning to reveal more details about the mysterious visitor.

The new findings, published in Nature Astronomy, suggest that the surface of 'Oumuamua is coated in a 'dry crust'.

"The 'organic-rich layer' is composed of carbon-based molecules and polymers," Alan Fitzsimmons from Queen's told IBTimes UK. "It was made by bombardment of the surface by interstellar cosmic radiation over millions of years, which transformed the surface dust and ice into a dark and stable surface."

The scientists think that 'Oumuamua's coating may have protected its icy interior from being vaporised as it passed within just 23 million miles from our Sun in September.

"We have discovered that the surface of 'Oumuamua is similar to bodies in our own solar system that are covered in carbon-rich ices, whose structure is modified by exposure to cosmic rays," said Alan Fitzsimmons from Queen's University.

"We have also found that a half-metre thick coating of organic-rich material could have protected a water-ice-rich comet-like interior from vaporizing when the object was heated by the sun, even though it was heated to over 300 degrees centigrade."

When cosmic rays come into contact with the surfaces of some small, icy objects in space, chemical reactions occur and new, organic molecules are formed – some of which are precursors to life as we know it.

In a separate study, to be published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, Michele Bannister and her colleagues from Queen's found that 'Oumuamua was the same colour as some of the icy dwarf planets they have been studying on the outskirts of our own solar system. This suggests that different planetary systems in our own galaxy contain minor worlds much like our own.

"We've discovered that this is a planetesimal with a well-baked crust that looks a lot like the tiniest worlds in the outer regions of our solar system, has a greyish/red surface and is highly elongated, probably about the size and shape of the Gherkin skyscraper in London," Bannister said.

"It's fascinating that the first interstellar object discovered looks so much like a tiny world from our own home system. This suggests that the way our planets and asteroids formed has a lot of kinship to the systems around other stars."

Scientists will continue to examine 'Oumuamua in more detail, with more revelations expected in the near future.

"Discoveries like this really help to give a little more insight into what's out there and encourages people to look up and wonder," Bannister said.