Pregnancy evolved in mammals 'by chance through ancient genomic parasites'

Pregnancy evolved in mammals completely by chance through "ancient genomic parasites", researchers have discovered.

An international team published their finding in Cell Reports, and has shown that thousands of genes evolved to be expressed in the uterus in early mammals – including those important for maternal-foetal communication and suppression of the immune system.

Study author Vincent Lynch, from the University of Chicago, said: "For the first time, we have a good understanding of how something completely novel evolves in nature, of how this new way of reproducing came to be.

"Most remarkably, we found the genetic changes that likely underlie the evolution of pregnancy are linked to domesticated transposable elements that invaded the genome in early mammals. So I guess we owe the evolution of pregnancy to what are effectively genomic parasites."

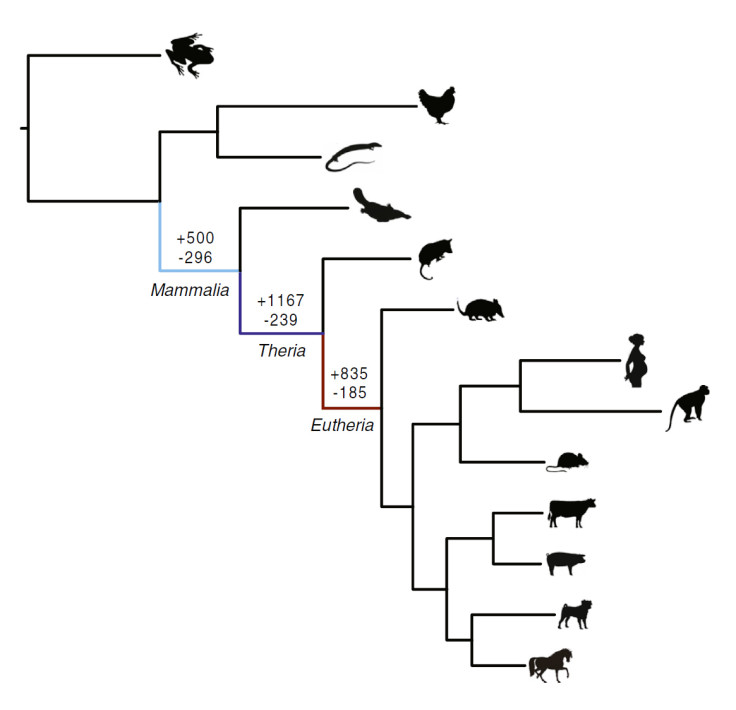

Researchers tracked the changes through cataloguing genes expressed in living animals, including placental mammals like humans, egg-laying mammals like platypus, birds, reptiles, and a frog. The changes started taking place about 220 million years ago over a period of about 50 million years.

They then used computer models and evolutionary method to reconstruct the genes expressed in ancestral mammals.

Findings showed that as we lost the eggshell, over 1,000 genes were turned on, many of which were involved in stopping the mother from viewing the foetus as a foreign body and rejecting it.

Speaking to IBTimes UK, Lynch said: "A foetus has a genome it inherits from its mother and a genome it inherits from its father. The mother's immune system should recognise all the genes from the paternal genome as foreign and the body will mount an immune response against them, because it's not her, it's something else. But that doesn't happen.

"The first step in the pregnancy is that the foetus has to say 'hey I'm here and I'm not a parasite'.

"The second step is that the mother has to recognise that signal and turn that signal into a localised suppression of the immune response in the uterus – telling the cells that would go around attacking foreign organisms to not do that – she turns them off."

Why these changes happened, however, was just luck. The genomic parasites were entirely self-serving and gave rise to pregnancy as we know it as a result of their changes: "They weren't trying to do this for us – they just by chance had the ability to turn genes on and off," Lynch said.

Discussing what is next in terms of this research, he added: "We've just found there are thousands of genes that evolved to be expressed in the uterus. We can infer the function of those genes based on lots of things, but we'd actually like to know specifically what they're doing. So now we're testing what those genes do one at a time.

"Pregnancy is really complicated. It goes wrong a lot. You have infertility, we have people who for some reason have a lot of spontaneous abortion, where the pregnancy never goes to term. If we understand how something evolved, we can have a really good understanding of how it works. And if we understand how it works, then maybe we can understand what goes wrong."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.