Prehistoric hippo-sized marine mammal had jaws that sucked like a vacuum cleaner

A newly discovered species of the extinct Desmostylia group has been unearthed, shedding more light on the mysterious marine mammal family. The new species – which has been dubbed Ounalashkastylus tomidai – had a "unique" jaw structure that allowed the animal to literally suck vegetation from shorelines.

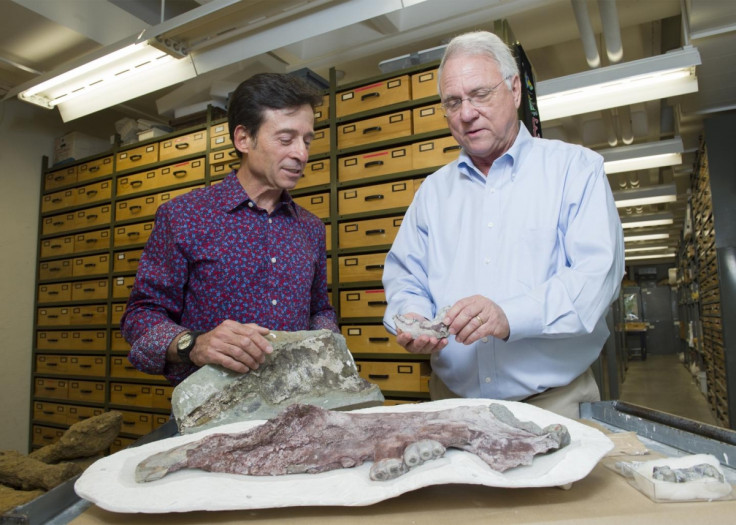

"The new animal, when compared to one of a different species from Japan, made us realise that Desmos do not chew like any other animal," said study co-author Louis L Jacobs from Southern Methodist University, Dallas, a professor of earth sciences. "They clench their teeth, root up plants and suck them in."

To eat, the animal positioned its lower jaw against its upper jaw and used the muscles in its mouth to vacuum up vegetation, according to the study published in Historical Biology. The fossils were found on Unalaska Island, with all the different variants of the Desmostylia family residing in the North Pacific. "That's the only place they're known in the world − from Baja, California, up along the west coast of North America, around the Alaska Peninsula, the storm-battered Aleutian Islands, to Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula and Sakhalin Island, to the Japanese islands," Jacobs said.

At least four Ounalashkastylus tomidais were found on Unalaska Island, with one of them being a baby. "The baby tells us they had a breeding population up there. They must have stayed in sheltered areas to protect the young from surf and currents," said Jacobs.

The Desmotylia family only roamed the earth for around 23 million years, with the last of them dying out 10 million years ago. The Ounalashkastylus tomidai went extinct 23 million years ago.

The marine mammal was the size of a hippopotamus, and it remains a mystery as to why they were only around for a relatively short period of time in prehistoric terms. However, the study's co-author, Anthony Fiorillo, vice president of research and collections and chief curator at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, thinks the marine mammals were actually very successful.

"Our new study shows that though this group of strange and extinct mammals was short-lived, it was a successful group with greater biodiversity than had been previously realised," Anthony Fiorillo said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.