Pussy Riot, the Arctic 30 and the Bolotnaya 27: When Will Russia's Litany of Shame End?

The plight of Nadezdha Tolokonnikova throws yet more light on the horrendous iniquity of Russia's justice system

Finally, a rare, positive human rights development in Russia. An independent activist was released from pre-trial detention and transferred to house arrest earlier this month. It might seem like a small step, but in today's Russia its significance should not be underestimated.

The activist, Mikhail Savva, had been targeted by the Federal Security Service (FSB) with politically motivated fraud charges. He had been behind bars since his arrest in April. But only when details became public that the FSB had for months been threatening him with treason charges because he "meets too often with foreigners" did a court hastily release him pending the rest of his trial.

This was only the most recent illustration of the warped nature of justice in politically tinged cases in Russia. All these cases reveal a common motivation: impose excessive charges against people the authorities find inconvenient or challenging. The Russian authorities presumably hope to silence these people and send a chilling message to others like them.

Mikhail Savva's story needs to be told so that the world can see how Russian authorities try to abuse the justice system to lock up inconvenient people.

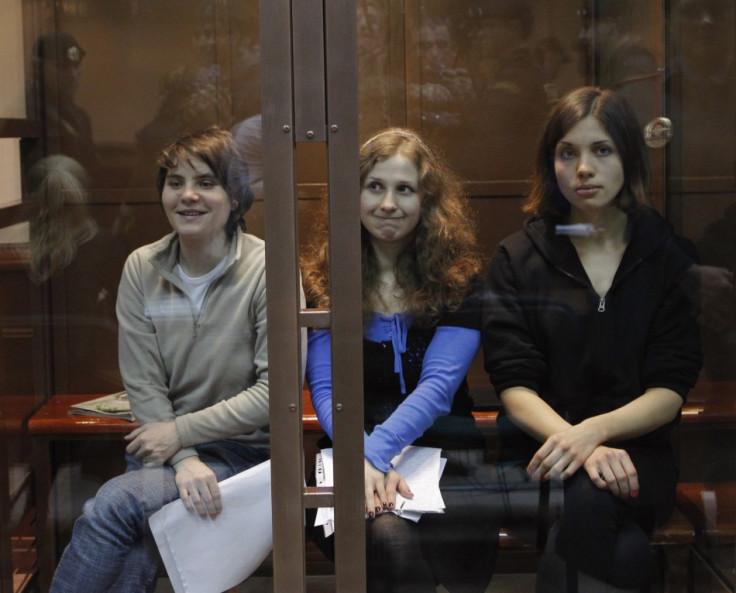

But you would need to have been on Mars not have already heard of Pussy Riot, the feminist punk performers sentenced in 2012 to two years in prison on "hooliganism" charges for their political stunt in Moscow's Christ the Saviour Cathedral. Their case clearly demonstrates how Russia's legal system can be distorted by political pressure.

One of the two Pussy Riot members still serving out sentences, Nadezdha Tolokonnikova, recently surfaced in a Siberian hospital after several weeks in which her family had no idea where she was. She had been transferred from the prison colony whose inhuman conditions she had exposed in a letter that made headlines worldwide.

The Pussy Riot verdict shows that the authorities are willing to distort justice to deliver very harsh sentences against people who themselves deliver harsh criticism of the government. On December 10, the Supreme Court ordered a Moscow court to re-examine the verdict. Let's hope for another piece of good news.

Sadly, Tolokonnikova's case is far from unusual, though. Look at the Greenpeace Arctic 30 activists, who have been charged with "hooliganism" for their non-violent protest against drilling in the Barents Sea – exactly the same charge brought against Pussy Riot. Unlike Pussy Riot, all of the Greenpeace activists were ultimately released on bail pending trial. But like the Pussy Riot women, the Greenpeace activists are facing a distorted and disproportionate charge. Under Russian law hooliganism is disorderly conduct that is either motivated by hatred or committed with a weapon. It's hard to see what the authorities will say were weapons in the Greenpeace case, or how they can prove the hate motive, and if so against whom.

Then there are the protesters arrested in connection with a demonstration in Moscow's Bolotnaya Square in May 2012, the day before President Vladimir Putin's most recent inauguration. The government is prosecuting 27 people on the charges of mass riots and violence against officials in connection with protester-police clashes that were sporadic and small-scale. Fourteen of those arrested have been behind bars for months either awaiting trial or as their trial drags on. At least half have been in jail for more than a year. There is also very strong evidence that some of them were not involved in any violent acts. But the the Bolotnaya trial appears designed to send the same kind of warning to Russian public – think twice before joining street protests.

Each of these cases is designed to make Russians think twice before they do anything that annoys or challenges the government. What the news about Mikhail Savva, Pussy Riot, the Arctic 30 and the Bolotnaya protesters should do is to make the government think twice about warping the judicial system for obvious political ends.

Rachel Denber is deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia Division at Human Rights Watch, specialising in countries of the former Soviet Union. She has authored reports on a wide range of human rights issues throughout the region.

You can follow Rachel on Twitter @Rachel_Denber, or find out more about HRW and its work by clicking on the following link.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.