Qatar World Cup 2022: Photos show the conditions faced by migrant labourers

Amnesty International has urged Fifa to put pressure on Qatar to improve conditions for labourers working on venues for the 2022 World Cup. Construction workers from some of the world's poorest countries, including Nepal and Bangladesh, are charged recruitment fees by agents in their home countries, housed in squalid accommodation and barred from leaving the country by employers in Qatar who confiscate their passports, Amnesty said in a report.

Amnesty interviewed migrant labourers, who said they went into debt to pay recruitment fees — illegal under Qatari law — ranging from $500 to $4,300 to secure work. Most discovered on arrival that they would be paid less than promised by recruiters back home. Some of those interviewed reported earning basic salaries of well below $200 a month, plus allowances of around $50 a month for food.

Mustafa Qadri, Amnesty's Gulf migrant rights researcher, acknowledged that Qatari authorities have taken some steps to improve labour conditions, but said they must put far more priority on the issue as preparation for the games intensifies. The government has made changes, including moving some labourers into improved accommodation and instituting a "wage protection system" to tighten oversight of salary payments. It says it is committed to doing more, calling its reform efforts a "work in progress." It said in a statement that worker welfare is a top priority.

New accommodation area for workers show clean dormitory areas with privacy curtains around the beds, plus gleaming bathrooms, a brand new medical centre and a gym.

These pictures are a far cry from the photos taken in a private workers' accommodation area a year before. These pictures showed filthy kitchens and dormitories, with workers crammed together on bunk beds with no privacy. It is unclear how many workers still live in these conditions.

Seven Nepalese men who worked on Khalifa Stadium for a subcontractor told Amnesty they had wanted to return home to check on their families after the earthquakes that hit Nepal in 2015 but their employer did not allow them to leave.

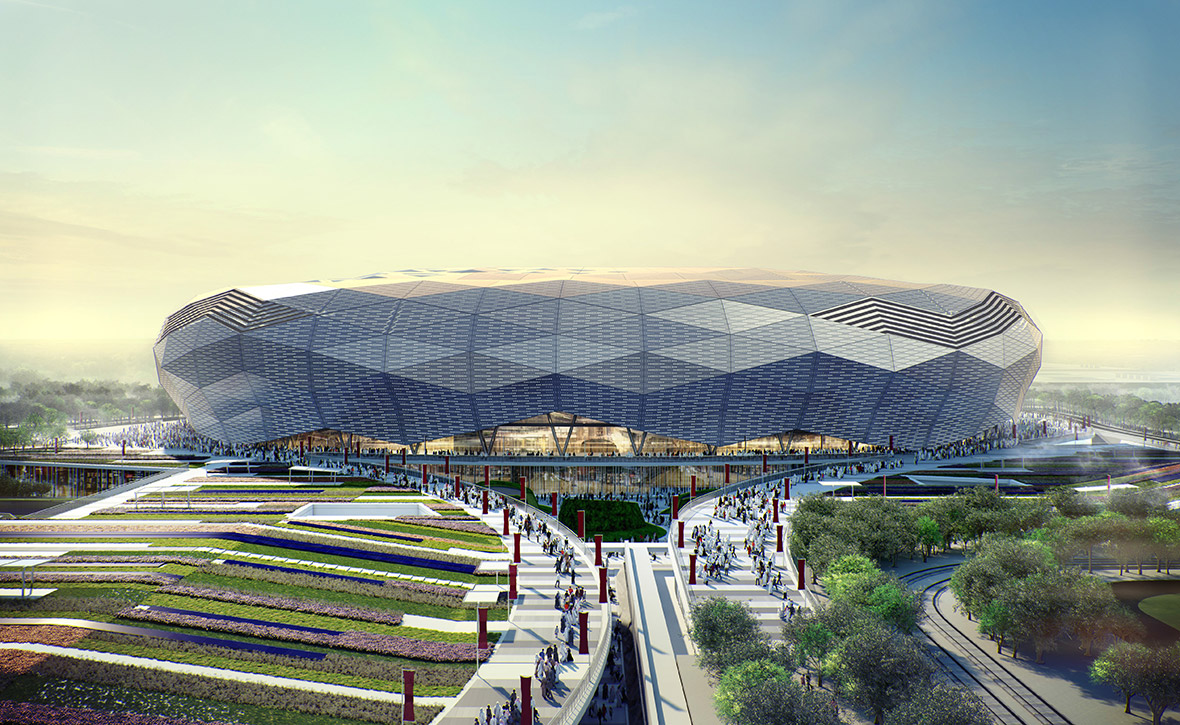

The Amnesty report pointed to abuses by small sub-contractors who do not appear to have been vetted by the tournament's organisers. The watchdog group said staff from one labour-supply firm threatened to withhold pay and report workers to police to exact labour from migrants. Amnesty said it interviewed 132 workers involved in the rebuilding of the Khalifa stadium, a vast sporting complex in Doha that is part of a $200bn construction boom in the gas-rich Gulf state that will host a World Cup quarter-final.

The head of Qatar's Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy agreed that Amnesty had identified challenges in worker conditions, but said Doha was working to reduce these kinds of abuses which he said occur on construction sites all over the world.

Since winning the World Cup in 2010, Qatar has spent tens of billions of dollars on a new port, metro system and airport. Hundreds of thousands of south Asians were recruited and they account for 94% of the 2.1 million population.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.