Rio's Olympic legacy: Crime, corruption, recession, pollution and derelict venues

Rio de Janeiro one year on from the Olympic Games opening ceremony on 5 August 2016.

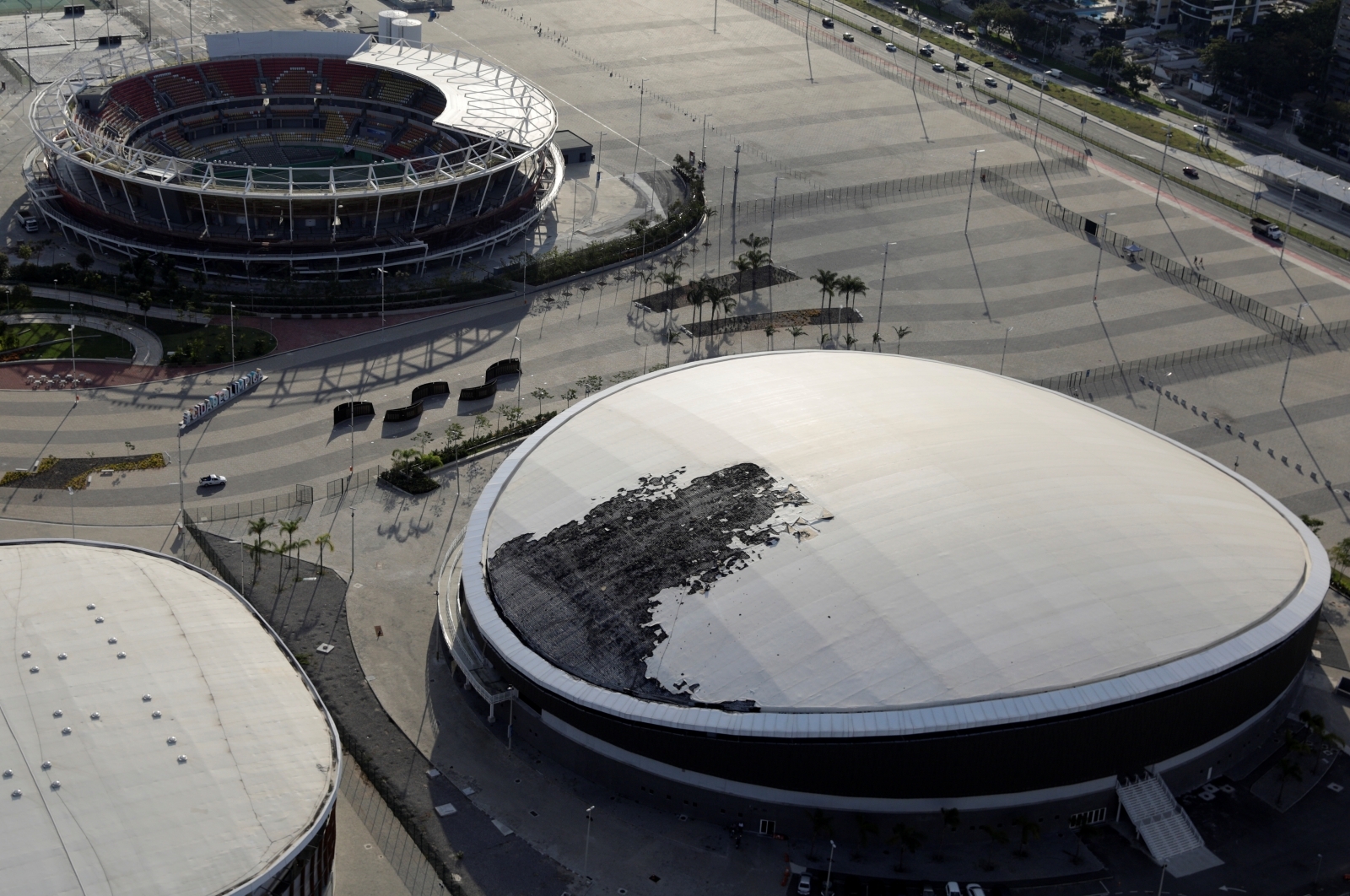

One year on from the Rio 2016 Olympic Games opening ceremony, most of the sports venues are vacant and dilapidated, the polluted waterways are even filthier than before, and city authorities have had to call in armed soldiers to patrol its streets and beaches to curb rising violence and organised crime.

The legacy of Rio 2016 has fallen far short of the glorious future promised by the organising committee. IOC President Thomas Bach said the games would be a "catalyst for transforming Rio into a modern metropolis that is even more beautiful than before" and organising committee head Carlos Nuzman claimed Rio de Janeiro would be the next Barcelona, a city transformed by the games.

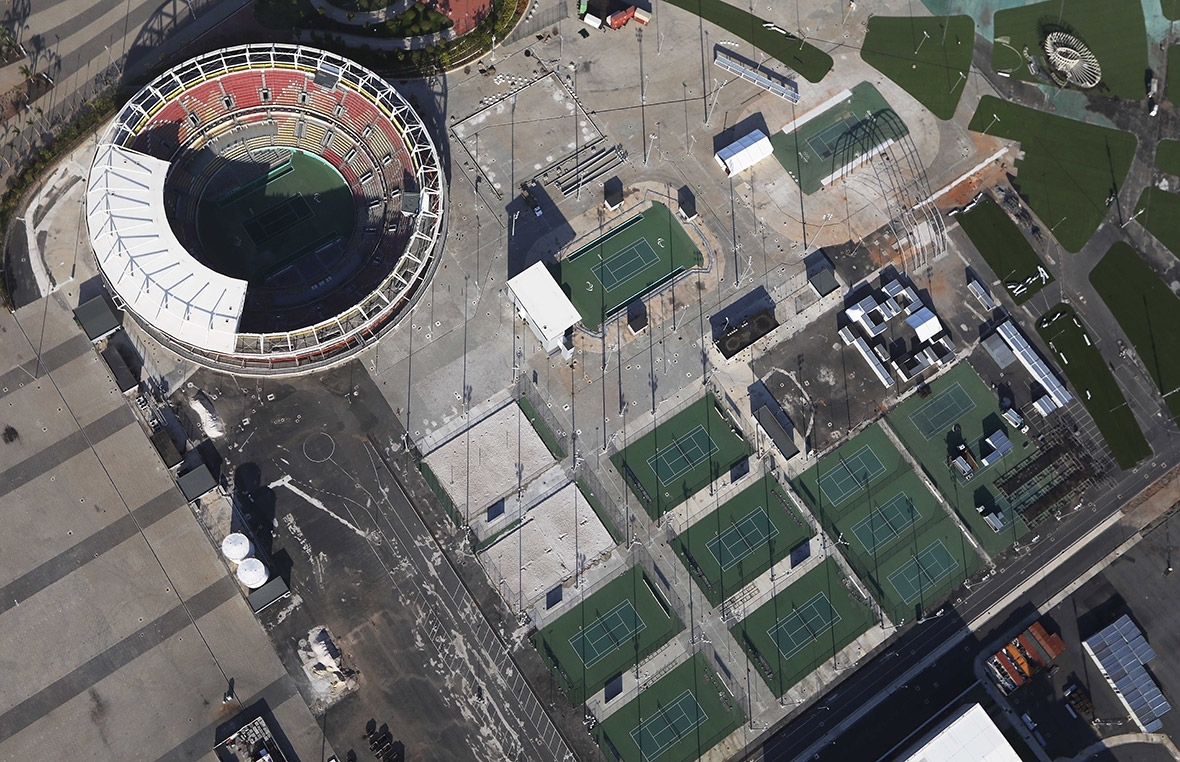

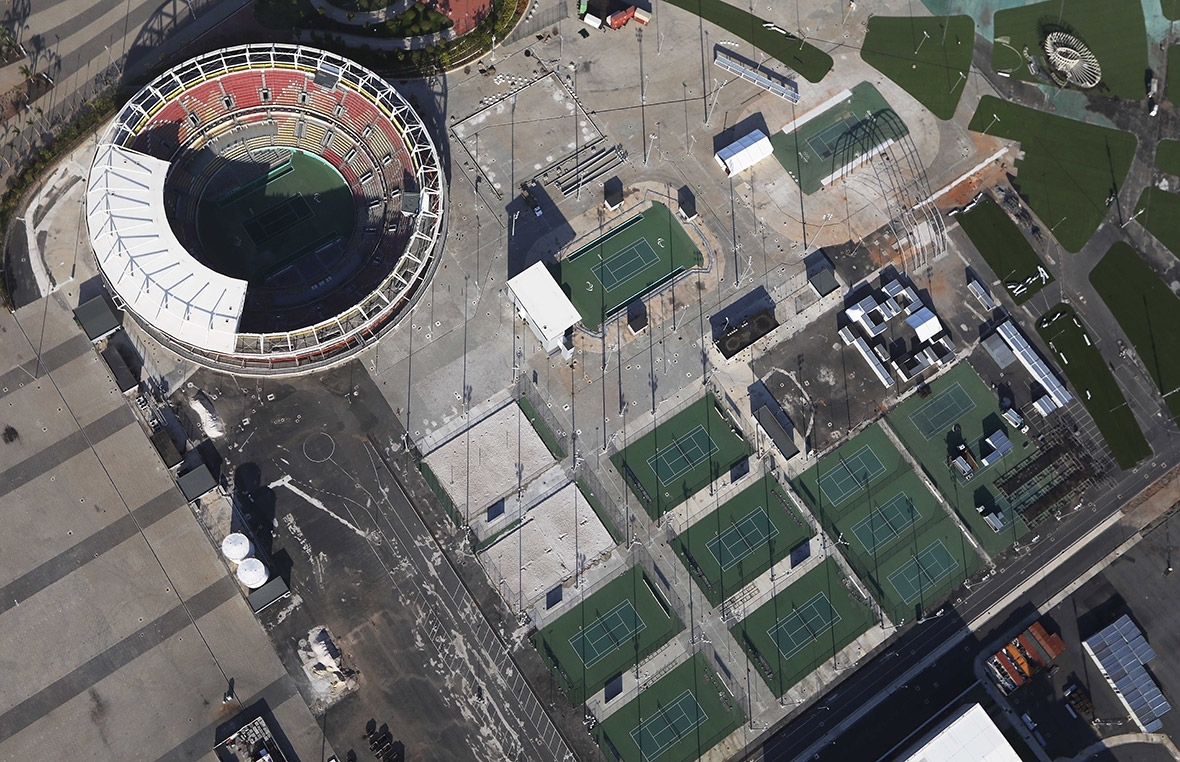

The Olympics left a half-dozen vacant sports arenas in the Olympic Park and 3,600 empty apartments in the boarded-up Olympic Village. The eerily empty park offers few amenities: no restaurants, no shade and nothing much to do except gawk at deserted arenas. The track and roof of the velodrome were damaged in a fire when a small, hand-made hot-air balloon landed on it. Deodoro, a major complex of venues in the impoverished north, is shuttered behind iron gates.

A $20 million (£15.2m) golf course is struggling to find players and financing. The clubhouse is mostly unfurnished, and it costs non-Brazilians 560 reals (£136) for 18 holes and a golf cart.

Organisers and the International Olympic Committee say Rio needs time to develop these venues, and blames Brazil's deep recession for most of the problems. A prosecutor disputed this, saying the Olympic Park "lacked planning how to use white elephant" sports venues. Many were built as part of real estate deals that have yet to pan out.

Rio 2016 organisers promised to clean up polluted Guanabara Bay in their winning bid in 2009. During the Olympics, officials used stop-gap measures to keep floating sofas, logs and dead animals from crashing into boats during the sailing events. Since the Olympics, the bankrupt state of Rio de Janeiro has ceased major efforts to clean the bay, its unwelcome stench often drifting along the highway from the international airport.

The city has seen some benefits from the games. The Olympics left behind a new subway line extension, a high-speed bus service and an urban jewel: a renovated port area filled with food stands, musicians and safe street life in a city rife with crime. These probably would not have been built without the prestige of the Olympics. But the games also imposed deadlines and drove up the price. A state auditor's report said the 9.7 billion real (£2.3bn) subway was overpriced by 25 percent.

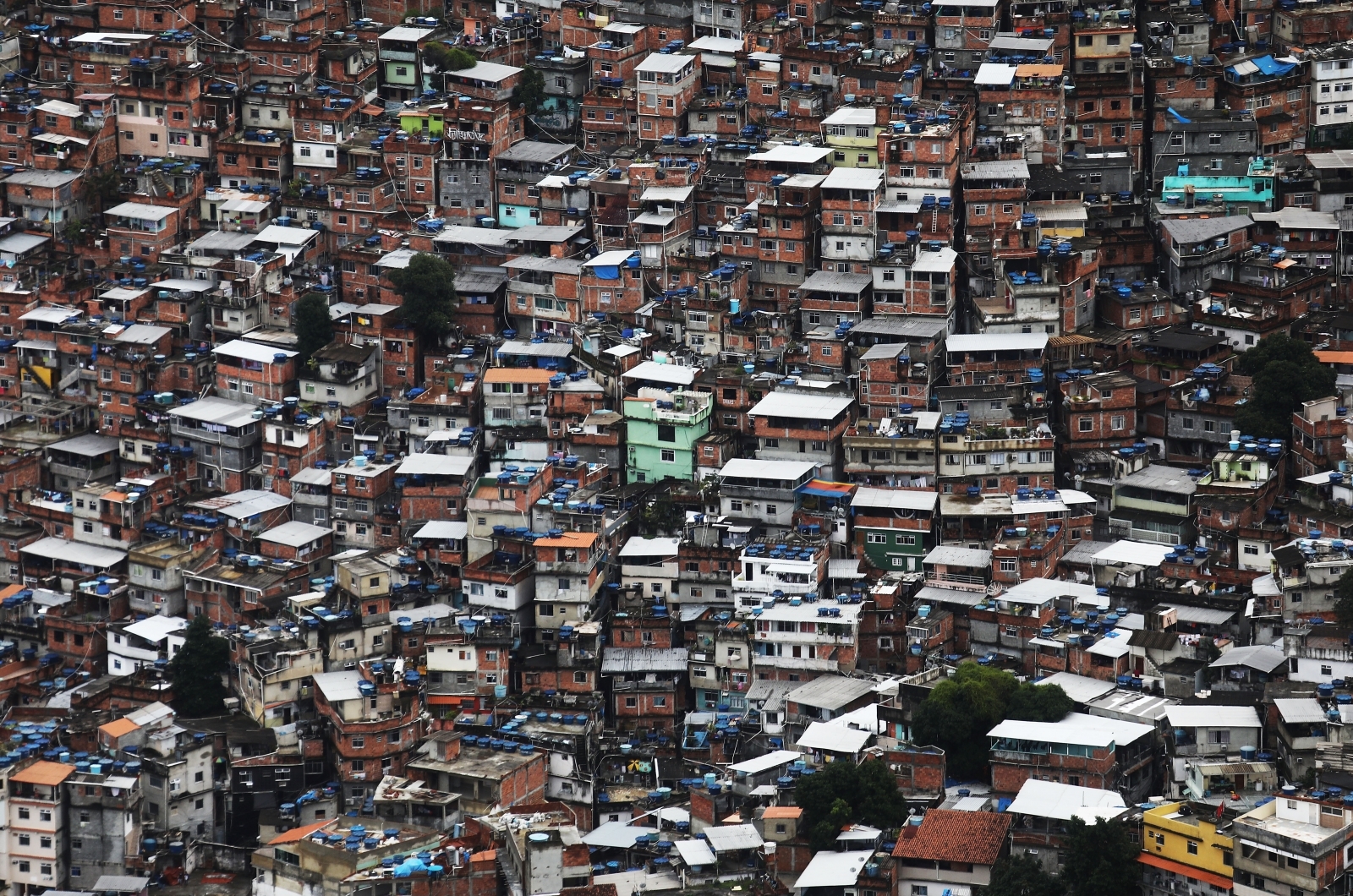

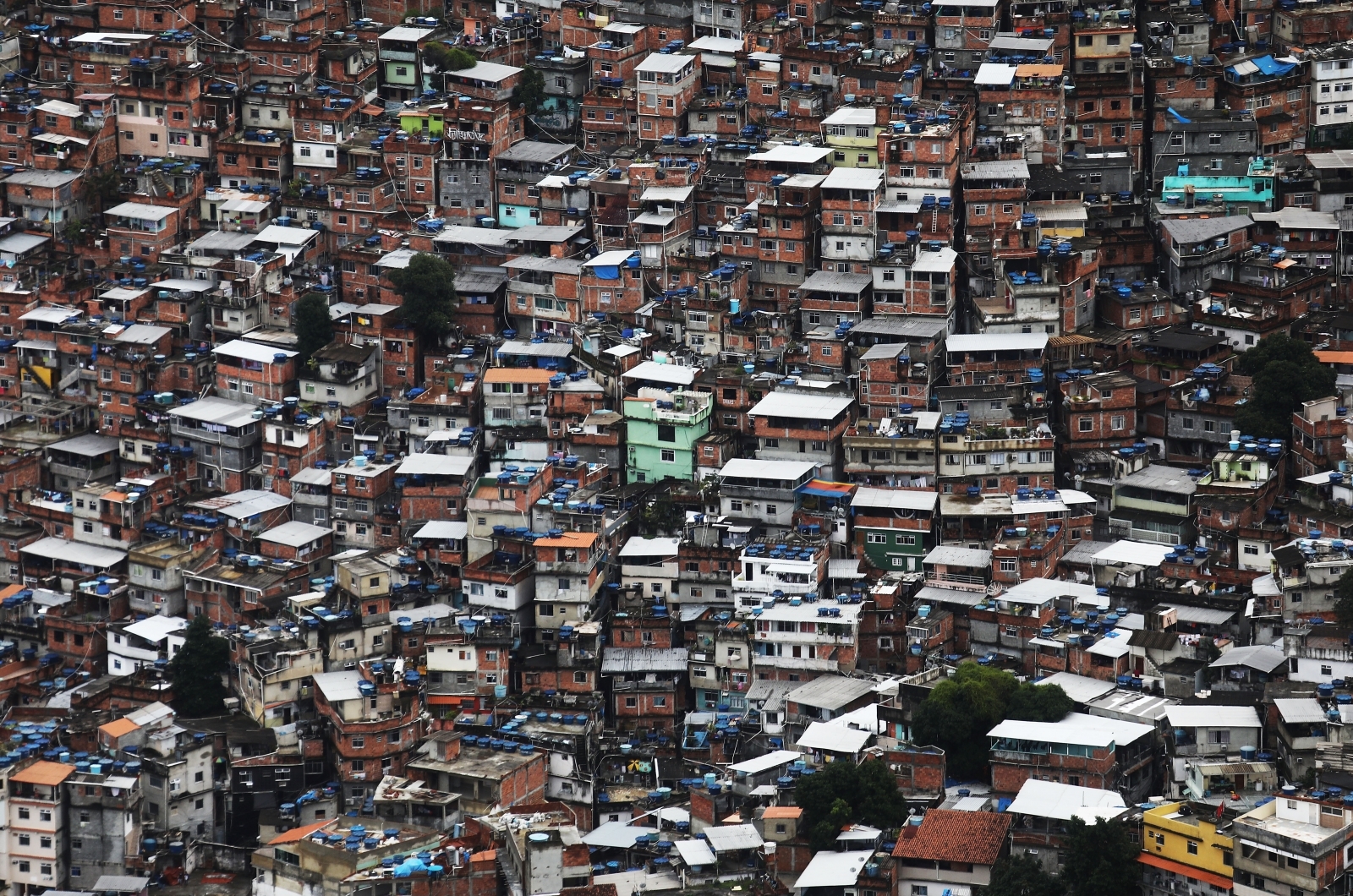

The city is still fractured by searing inequality amid Brazil's deepest economic downturn in 100 years. The games took place mostly in the south and west of the city, which remains white and wealthy. The rest is still a hodgepodge of dilapidated factories and hillside slums of cinderblocks, tin roofs and open sewers.

An average of three people were killed every day by stray bullets in the first six months of the year in Rio de Janeiro. A rise in criminal assaults and increasing shootouts between drug traffickers and police have led authorities to acknowledge that much of the city is out of their control. The deployment of up to 10,000 armed soldiers, plus hundreds of police and highway patrol officers, is aimed at fighting the organised crime gangs that control many of the city's slums.

Official data shows murders in Rio de Janeiro state rose 14 percent to 3,755 in the first half of 2017 from a year earlier. The number of people killed by Rio's police, long criticised for their tactics, spiked more than 45 percent to 581.

The situation is unlikely to improve anytime soon, with Rio state facing a 21-billion-real (£5.1bn) deficit this year. Rio barely managed to keep it together for the Olympics, needed a government bailout to hold the Paralympics and then collapsed under a grinding recession and sprawling corruption scandals. Brazil says it spent $13 billion (around £10bn) in public and private money to organise the Olympics, but some estimates suggest $20bn.

Many games-related projects since then have been tied to corruption scandals that marred the games and drove up costs. Federal police and prosecutors have linked overpriced projects to bribes between politicians and construction companies.

Some of the politicians behind the Olympics have been accused of corruption and bribery, and organisers still owe creditors millions. Former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who wept when Rio was awarded the games, was convicted on corruption charges and sentenced to more than nine years in prison.

Former Rio de Janeiro Mayor Eduardo Paes, the local moving force behind the Olympics, is being investigated for allegedly accepting at least 15 million reals (£3.6m) in payments to facilitate construction projects tied to the games. He denies any wrongdoing.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.