Scientists Create Adhesives Inspired by Lizards' Sticky Feet

Inspired by the way lizards are able to stick to almost any surface, University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers have invented a new material called Geckskin that could beat common adhesives like Blu-Tack and sticky tape.

The research, headed by Prof Alfred Crosby of the Polymer Science and Engineering Department, is published in an article entitled "Creating Gecko-Like Adhesives for 'Real World' Surfaces" in the Advanced Materials journal.

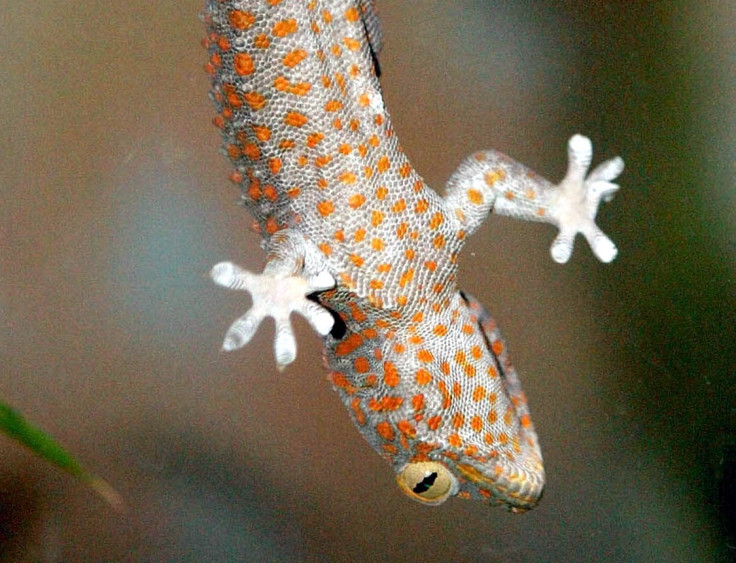

Geckos have sticky feet with tiny microscopic hairs that are attracted to surfaces by Van Der Waals' forces, which state that weak electric forces attract neutral molecules to form bonds.

Rather than try to mimic the tiny microscopic hairs, the researchers decided to replicate the "draping adhesion" effect that the skin, tendon and bone in the feet provide, using soft elastomers combined with ultra-stiff materials like glass fibre and carbon fibre.

By "tuning" the stiffness of the materials, it is possible to make a strong adhesive connection that conforms to the surface and is reusable without losing its stickiness.

In a video published by the researchers, Geckskin is able to stick an LCD screen onto various surfaces, including sheet metal, different types of painted walls, wood, glass, marble, concrete and steel.

"Imagine sticking your tablet on a wall to watch your favourite movie and then moving it to a new location when you want, without the need for pesky holes in your painted wall," said Crosby.

The researchers say that Geckskin is as sticky as a lizard, but the material has been scaled up to hold far more weight per square inch.

"The gecko's ability to stick to a variety of surfaces is critical for its survival, but it's equally important to be able to release and re-stick whenever it wants. Geckskin displays the same ability on different commonly used surfaces, opening up great possibilities for new technologies in the home, office or outdoors," said biology professor Duncan Irschick, who co-authored the paper.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.