South Sudan refugee exodus to Uganda raises spectre of Rwanda genocide

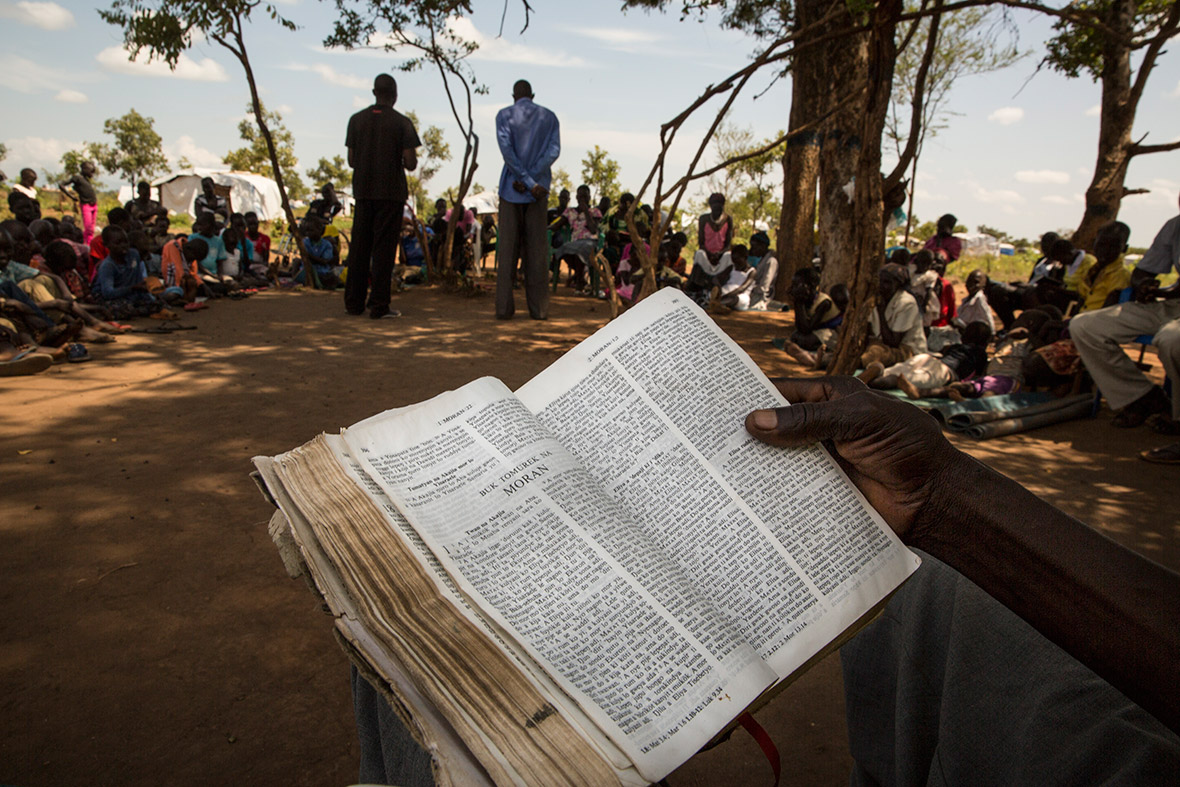

Award-winning photographer Paula Bronstein documents the biggest refugee movement in Central Africa since the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

More than a million people have fled South Sudan since fighting erupted in late 2013. They have taken refuge in many countries – including Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan – but Uganda, directly to the south, has received the most. Uganda now hosts about 600,000 refugees, with more than half arriving after July 2016 following the outbreak of fighting in Juba between forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar.

The ongoing conflict has led to ethnically targeted mass killings, rapes, torture, forced displacement, and destruction of property. The world's youngest country has experienced ethnic cleansing and teeters on the brink of genocide, according to the United Nations. Award-winning photographer Paula Bronstein spent some time at the Nyumanzi transit facility and the Pagarinya refugee camp in northern Uganda to document the plight of Sudanese refugees.

South Sudan now joins Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia as countries which have produced more than a million refugees. While some South Sudanese may attempt to head for Europe, the numbers within Uganda, in East Africa are comparable in scale to recent refugee flows to Europe from the Middle East, and their traumatic experiences due to war are horrific. They left their home with no idea of when they can ever go back.

More than 85% the refugees in this recent influx are women and children, to make matters worse many children have lost one or both of their parents, some forced to become primary caregivers to siblings. Displaced people arriving in Uganda in recent months come mostly from South Sudan's equatorial regions where waves of ethnic killings, sexual violence, looting, burning and opportunistic crime have turned villages and towns into death traps. Buses ferry in new arrivals daily: haggard and hungry children, women cuddling small babies, elderly women and just a few middle-aged men.

More than 2,000 Sudanese refugees are entering Uganda every day. The UN estimates 300,000 more people will arrive this year in the biggest cross-border exodus from any central African conflict since the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Those fleeing have turned Uganda's northwest from an empty bushland into a sprawling complex of refugee settlements. Unable to cope with the huge influx, relief agencies have had to implement stringent food rationing in the camps.

When South Sudan gained independence from Sudan in 2011 it was hoped it would end decades of civil war between the largely Arab, Muslim north and the predominantly African, Christian or animist south. However, conflict erupted in 2013 when Kiir, a member of Sudan's largest and dominant ethnic group, the Dinka, fired Machar, a Nuer.

The fighting has spilled south and west from Juba, laying waste to towns and villages and uprooting their inhabitants. Most of those arriving in Uganda are from smaller tribes in the southern part of the country, and have personal accounts of ethnic pillage, rape and murder - in many cases at the hands of Dinka militiamen.

So far, Uganda is keeping its doors open to the humanitarian disaster, and sticking by its policy of granting refugees freedom of movement and work, and access to public services such as schools and clinics. Unlike other countries in the region, Uganda has embraced the refugees, according to Charlie Yaxley, a spokesman for the UN refugee agency. "Many Ugandans themselves have previously been refugees, and you typically hear expressions of solidarity from the Ugandan people," Yaxley said.

The United Nations Human Rights Council has reminded Kiir's government of its responsibility for protecting the population against genocide and the government has said it will let a 4,000-strong regional protection force bolster the UN's existing peacekeeping mission.

Reporting for this story was made possible by the International Women's Media Foundation African Great Lakes Reporting Initiative.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.