Stamp duty reform: Sneaky George Osborne gives Tories economic boost before crunch 2015 general election

Stamp duty reform was the big populist rabbit pulled from Chancellor George Osborne's hat in his last Autumn Statement before the general election.

It was widely welcomed as a necessary change to an outdated and clunky tax system. But Osborne may have just pulled a greater magic trick than plucking rabbits out of hats.

Research shows relaxing stamp duty pushes up house prices by quickly increasing activity in the market, which then provides stimulus for the wider economy.

He could have just given the Conservatives a sneaky economic boost for the months leading up to the knife-edge election, in which polls suggest there is little difference between them and the opposition Labour party. Here's how.

What George Osborne is changing about stamp duty.

Osborne has, overnight, radically changed the stamp duty regime. Under the system, buyers of property are required to pay the tax on their purchase. The amount of tax is decided by the value of the property being purchased.

In the old "slab" system, each stamp duty threshold saw a drastic increase in the amount of tax a property buyer would pay. For example, a person paying £250,000 for a property – just £1 below the threshold – would owe stamp duty of £2,500. A person paying £250,002 – just £1 above – would owe £7,500.

What Osborne has done is to make it like the income tax system. So from now on, you would pay 1% on £125,000 to £250,000 of the property's value. Then you would pay 3% on any amount between £250,000 and £500,000.

For example, if you bought a property worth £300,000, you would pay 1% on the £125,000 that fell between the 1% threshold and 3% on the £50,000 that fell into the next one.

Before, you would have paid £9,000 in stamp duty on a £300,000 house. Now you would pay £2,750. It is a drastic reduction in the amount owed when compared to before.

Here is how the rates and thresholds have changed after Osborne's Autumn Statement:

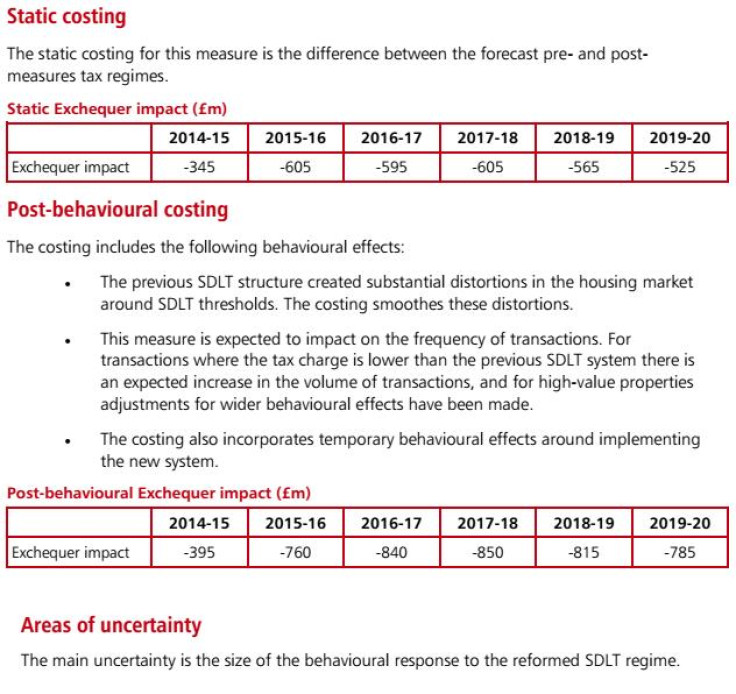

And here's how much the Treasury thinks it will cost them each year in lost tax revenue:

What a 2013 study shows us about stamp duty and house prices.

In 2013, study was published called Housing Market Responses to Transaction Taxes: Evidence From Notches and Stimulus in the UK. It's by two London School of Economics academics: Michael Carlos Best and Henrik Jacobsen Kleven.

They trawled 10 million property transactions in the UK between 2004-2012 and analysed the effects of the stamp duty system, as well as changes to it, on the housing market and economy.

Because there was such a big jump in the tax rate between the stamp duty bands, there tended to be "bunching" of house sales at prices below them. This is where there was demand from homebuyers who can't or won't pay a higher price because of the larger stamp duty rate.

The gap in house prices between the stamp duty cutoff and where transactions begin again is substantial. For example, at the £250,001 threshold where stamp duty was charged at 3%, the increase in the tax liability rises by £5,000 from the rate below it.

How the new system affects demand.

Person A wants to sell their home, which they think is worth around £255,000. Person B wants to buy the home, but doesn't want to pay thousands of pounds more for the higher stamp duty rate above £250,001.

Under the old system, Person B would try to buy the house at lower than this threshold. In order to meet the demand and sell their house, Person A would have to bring down their house value. Let's say the transaction closes at £250,000.

The new stamp duty system gets rid of the sudden tax cliff above £250,001. So now, Person B would be more inclined to pay a higher price. Which means Person A could get away with a £255,000 value on their home as demand would hold up where the old stamp duty system would have killed it off. So Person A's house price rises.

There is a £25,000 "hole" between the cutoff and where house prices begin selling at again "implying that the most responsive agents reduce their transacted house value by five times as much as the jump in tax liability".

There is a similar situation at all other stamp duty cutoff points. What Osborne has done is flattened the whole stamp duty tax system to get rid of the sudden tax spikes that choked off demand for houses priced just above each threshold and so encouraged bunching below it.

What the reforms will probably do is push up house prices because there is no sudden increase in the stamp duty rate choking off demand above the thresholds.

Why George Osborne might have done it now.

We are heading into what will be a very close election in 2015. What Osborne wants most of all is a positive economic story to sell to voters, to convince them that the pain of austerity is worth it and that his tough policies over the years since 2010 have been vindicated.

The economy is growing at a rate of 3% in 2014, the fastest of any developed Western country. But Oborne's facing some trouble ahead.

The housing market has slowed down more than expected. Regulators have tightened mortgage credit conditions over affordability concerns: house prices have risen sharply while incomes remain subdued and an impending interest rates hike will drain household finances.

What's more, the eurozone economy is stagnating, there is an ongoing slowdown in key emerging markets like China and India, and geopolitical crises still surround Russia and the Middle East. All of these issues are looming over the UK.

Osborne wants to ensure that he can overcome any blips in the short-term ahead of the election. The last thing Tories need is a renewed economic slowdown as they start canvassing on the doorsteps. And his stamp duty reform may just give them the boost they need.

What the 2013 study says is that it can take three or four months for things to settle out when changes to stamp duty are made, as people and prices readjust to the new order.

"Once we account for the built-in sluggishness due to the time it takes to complete a housing contract, the market adjusts to a new stable equilibrium remarkably quickly," it said.

"The overall finding is that prices and activity in the housing market respond sharply and quickly to transaction taxes in the way that economic theory predicts."

What we also know is that there's a big boost to the economy when housing market activity picks up. The study looked at the stamp duty holiday between 2008 and 2009 for those buying homes worth between the £125,000 and £175,000 threshold that existed at the time.

"The 16-month stamp duty holiday was enormously successful in stimulating housing market activity, increasing the volume of house transactions by as much as 20% in the short run (due to timing and extensive responses) followed by a smaller slump in activity after the policy is withdrawn (as the timing effect is cancelled out)," it said.

"Due to the complementarities between moving house and consumer spending, these stimulus effects translate into GDP effects that are considerably larger than what has been found for other forms of fiscal stimulus such as income tax rebates. The successfulness of stamp duty stimulus is a result of the large distortions created by the tax in the first place."

Osborne's stamp duty reforms will likely lift the housing market in a similar way to the 2008/09 holiday. In turn, we'll see a quick boost to the economy over the coming three or four months. By the time of the 2015 general election in May, we'll have had the first quarter GDP figures, which would reflect this sudden uplift - a solid platform from which the Conservatives can campaign.

Perhaps it will mean GDP beats expectations. Or perhaps it'll offset any dip elsewhere in the economy. Either way, Osborne is hedging his bets ahead of the election with his stamp duty reform.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.