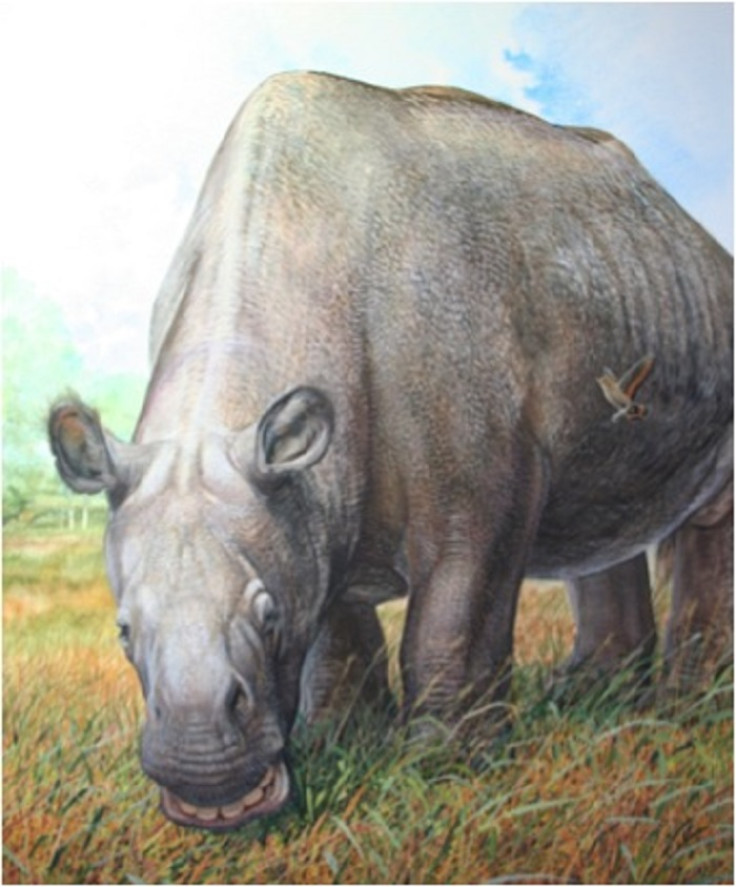

Strangest animal Darwin ever discovered was ancient relative of horse and rhino

They mystery behind the species Darwin called the "strangest animal ever discovered" has finally been solved by scientists through protein sequencing – showing it is closely related to the group that gave rise to horses and rhinos. South American ungulates have been a 200-year-old evolutionary puzzle, being placed on almost every branch of the mammalian family tree.

Published in the journal Nature, researchers from the American Museum of Natural History used fossil protein sequences that allowed them to look back in time 10 times further than possible with DNA.

"Fitting South American ungulates to the mammalian family tree has always been a major challenge for palaeontologists, because anatomically they were these weird mosaics, exhibiting features found in a huge variety of quite unrelated species living all over the place," said Ross MacPhee, one of the paper's authors.

"This is what puzzled Darwin and his collaborator Richard Owen so much in the early 19th century. With all of these conflicting signals, they couldn't say whether these ungulates were related to giant rodents, or elephants, or camels, or what have you."

Ancient DNA from the ungulate specimens would not have provided the answers they were looking for because it had not survived in the warm wet conditions in South America, where they were found.

However, by analysing collagen – a structural protein found in animal bones that survives for far longer – they were able to unlock the ungulate mysteries.

They screened 48 fossils of Toxodon platensis and Macrauchenia patachonica – the remains of which Darwin discovered 180 years ago in Uruguay and Argentina. They were able to obtain about 90% of the collagen sequence for both species.

Findings conclusively showed the closest living relatives of the species were perissodactyls – a group of animals that gave rise to horses, rhinos and tapirs. It also means they are part of the Laurasiatheria family – one of the major groups of placental mammals.

This suggests the ancestors of these ungulates likely came from North America over 60 million years ago – just after the mass extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs.

"Palaeontologists going back to the early 20<sup>th century believed there was a connection between sanus and perissodactyls, but because of the severe convergence problem, no one was really sure whether there were one or several different ancestral lineages involved," MacPhee told IBTimes UK.

"That's more or less how matters stood for the next century, with suggestions coming and going, but no clarity. We were able to show with the proteomic evidence that for at least sanu groups, the only credible close relative is perissodactyla, not African mammals as had been recently suggested for one of the groups.

"I would say that the big deal here is that molecules have satisfactorily solved a problem that 180 years of scientific pondering and argumentation had not managed to do."

The ungulates eventually disappeared about 10,000 years ago. Ian Barnes, from the Natural History Museum in London and another author of the paper, told IBTimes UK: "The South American ungulates probably took a couple of big hits in 'recent' times. Firstly, North and South America finally crashed into each other about three million years ago, forming the Panama Isthmus and enabling widespread migration between the two continents.

"We are pretty sure that this led to extinctions, as new communities formed with different predators and competitors for the native animals. More recently, the last 2.6 million years has been a time of cycling climate change, between cold, glacial periods, and shorter warm stages. Even tropical South America would have felt the effect of this, and particularly the last cold, dry stage which ended about the time our two species went extinct.

"Finally, humans arrived in South America, although I would personally doubt they were in enough numbers to impact on a healthy large mammal population."

Speaking about the future of collagen sequencing, he added: "The potential for future work is enormous, not just for ungulates, or even just for mammals. Collagen survives about ten times longer than DNA, and there may be other proteins that survive even longer."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.