Study on Monkeys Reveal Best Hope For HIV Vaccine

An experimental vaccine has appeared to protect monkeys from the species' version of the HIV virus, leading to optimism that a similar vaccine could be developed for humans.

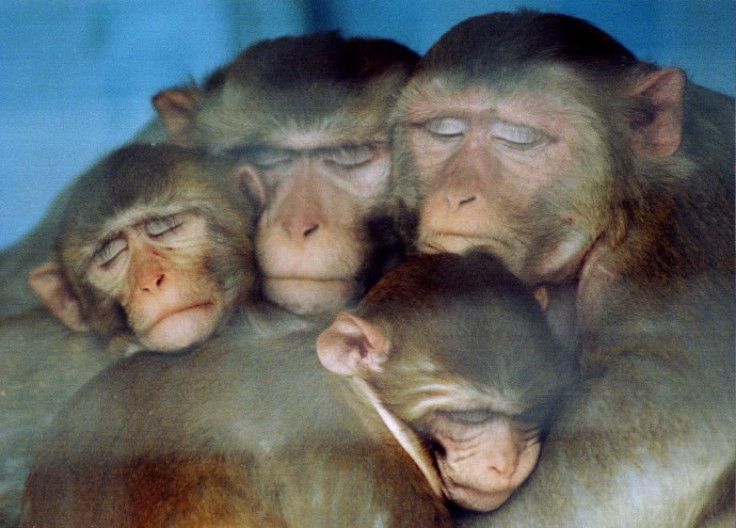

Scientists gave rhesus monkeys a vaccine against a form of the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus distantly related to the virus that causes AIDS in humans.

The monkeys that were vaccinated appeared be partially protected from the primate version of the virus, reducing their susceptibility to infection by 80 percent, according the report published in the journal Nature.

SIV vaccines have been successful before, albeit against SIV strains used to make the virus or strains that are easy to kill, but the protective effects has proved difficult to carry over to HIV.

The successful vaccines all contained an essential element called Env, which helped the virus bind the antibodies that can destroy it.

"The study demonstrates very clearly that in order to prevent acquisition of the virus, a vaccine needs to have an Env glycoprotein component," said Eric Hunter, professor of pathology and co-director of the Center for AIDS Research at Atlanta's Emory University who was not involved with the study.

"I would say this is significant progress in the process of trying to develop a protective HIV vaccine."

Some of the immune responses shown by the monkeys were also seen in the only HIV vaccine trail that has protected humans from HIV, known as the Thai trial, which showed that a vaccine could safely prevent HIV infection in a small number of volunteers.

This latest result is promising enough that the researchers are hoping to test the vaccines on humans next year.

"You always have to be a little bit careful of direct extrapolations from animal studies, but I think in this case, this is a level above the usual kind of a study," said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which provided funding for the study.

Because HIV is spread through so many ways - such as during sex, drug users sharing needles or via blood transfusions - there is no single way to prevent infection, meaning a vaccine is still considered the best hope to protect against the virus.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.