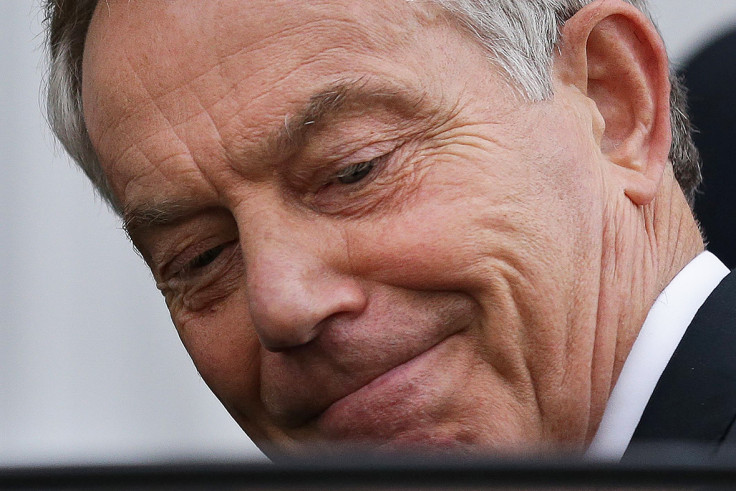

Tony Blair will be damned by history over the Iraq war - but his choice was between two evils

Tony Blair never had the option of keeping its hands clean over Iraq

Some of the exultant outpourings greeting the publication of the long-awaited Chilcot report into the Iraq war have reminded me of a line in Ian McEwan's novel Saturday. 'If [those who opposed the Iraq war] think that continued torture and summary executions, ethnic cleansing and occasional genocide [were] preferable to invasion, they should be sombre in their view.'

Today's report by Sir John Chilcot into why Britain helped wage war in Iraq in 2003 – a conflict that led to the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives – ought to be a cheerless and melancholy affair. If ever there was a time for quiet introspection – rather than ya boo triumphalism – this is it.

In retrospect, the years between 9/11 and the start of the Coalition's dazzling 'shock and awe' bombing campaign over Baghdad marked the end of one optimistic epoch and the beginning of another altogether gloomier one.

The 1990s had of course had their catastrophes – one of my first conscious political memories was of watching on television as Bosnians darted and dodged the bullets of the racist army of Radovan Karadzic during the siege of Sarajevo – but a discernible whiff of optimism was in the air.

This sense of optimism, which feels so wistfully naïve and antiquated today, came to an abrupt end at 8.46am on the morning of September 11, 2001, when American Airlines flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of New York's World Trade Centre. Over the course of that morning the optimism of the 1990s was incinerated by four successive fireballs of steel, jet fuel and human flesh.

A war on the Taliban in Afghanistan was the first emotional palliative offered to an American public traumatised by 9/11. But after Afghanistan, the eyes of the George W Bush administration soon turned towards Iraq. Following the Taliban's provision of shelter to members of Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, the prospect of a global outlier like Saddam Hussein working with fanatical jihadists was like the threat of a dark and thunderous cloud that might one day rain on the West.

The lesson both Bush and Tony Blair took from 9/11 and Afghanistan was clear: allow tyrannical regimes to produce weapons of mass destruction and incubate terrorism at your own peril. "Containment as we found with Al Qaida," Blair said in a 2002 memo to Bush, "is always risky. His [Saddam's] departure would free up the region."

The Bush administration had already decided to go to war with Saddam, regardless of where Tony Blair's Labour government stood. But buoyed by successful humanitarian endeavours in Sierra Leone and Kosovo, Blair wanted to be seen to be standing side by side with the US in its hour of crisis. As Chilcot reveals, Blair reassured Bush in the now infamous memo that "I'll be with you, whatever".

And so the UK "chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted", as Chilcot puts it. Military action was not, as it should have been, a last resort. Instead intelligence was marshalled to fit a decision that had already been taken. "The judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq's weapons of mass destruction – WMD – were presented with a certainty that was not justified," the report says.

Most damning of all, the planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam had been deposed were "wholly inadequate". This imperial hubris – both the US and Britain assumed that they could go into Iraq, topple the dictator and get out right away – accounts for the bloody and sectarian chaos that unfolded in Iraq between 2003 and 2011.

You either acquiesced in the continuation of one of the world's worst dictatorships, or you got rid of it with violence.

Both Bush and Blair forgot that the flowering of democracy requires more than opening the hatch of a B52 bomber. All cultures have "great intrinsic momenta and they cannot be rapidly turned in new directions", as the great historian of Stalinism Robert Conquest once wrote. Nor were the neo-Conservatives the armed wing of Amnesty International, as some commentators appeared to believe at the time.

In using 'flawed intelligence' (as Chilcot puts it) to make the case for war, and in failing to make any adequate plan for post-invasion, Blair will be damned by history. However it is worth remembering, beyond today's thunderous denunciation of the former PM, that the alternatives to war came with their own deadly cost.

There was never an option to keep one's hands clean over Iraq. Hussein's regime was, as Blair correctly pointed in the lead up to war '"..with the possible exception of North Korea, the most brutal and inhumane in the world".

Thus the choice before the British and American governments in March 2003 was not between good and evil, as the placard-wielding 'anti-war' protesters like to scream. It was between two evils. You either acquiesced in the continuation of one of the world's worst dictatorships, or you got rid of it with violence.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.