Tony Nicklinson's Daughter: Memory and Campaign for Legalised Voluntary Euthanasia Lives On

It was six weeks before my 18<sup>th birthday when dad had the stroke.

Thinking back to the moment I first saw him in the Athens intensive care unit still makes my chest ache and tears prick the corners of my eyes. I had to say goodbye to him as we were not sure if he was going to live.

I was so angry; there are so many unpleasant people in the world, why, of all people, was it my dad that had to suffer such a devastating stroke? We were such a normal, happy family so why did something so extraordinary and painful happen to one of us? It didn't make sense and I struggled to comprehend what we had done to deserve this.

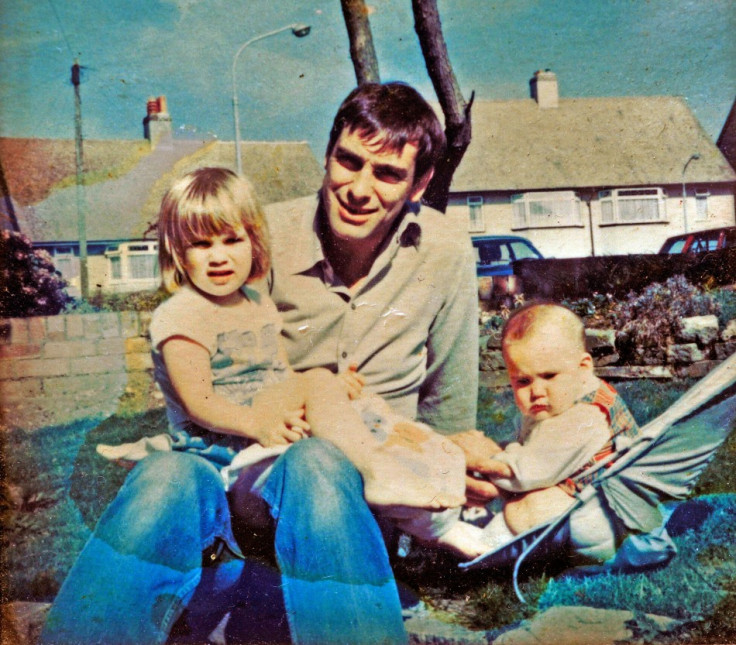

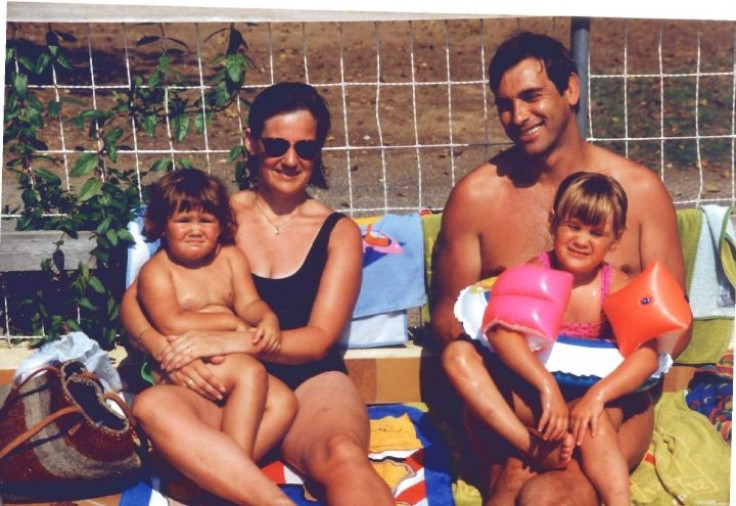

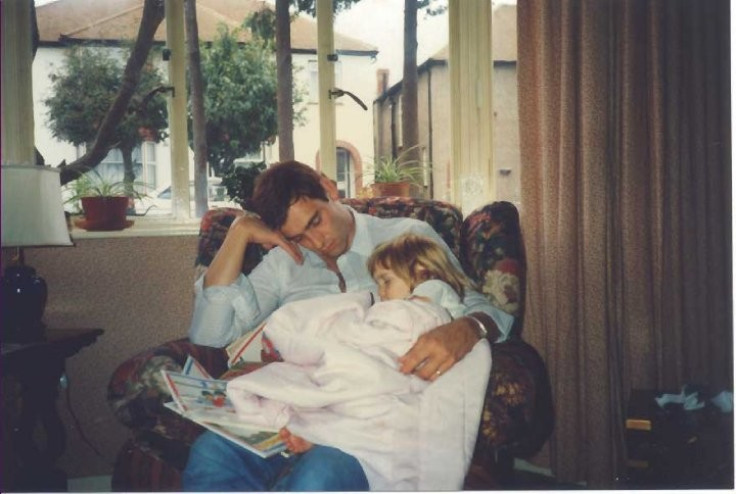

As a typical narcissistic teenager, to say I felt sorry for myself was an understatement. Growing up, I was a total daddy's girl and whilst I tried my best to enjoy my future, dad's disabilities completely changed our relationship and left a raw, gaping bullet hole. I experienced the usual milestones without him; my 18<sup>th birthday, moving to university, graduating, buying my first car and starting my career to name a few.

We had planned to celebrate my 18<sup>th birthday with a lush family meal; instead it was spent in an ICU unit preparing for the worst after we were told that dad has suspected septicaemia.

I hated Christmas, it was usually such a happy time and the festive season really hammered home how much things had changed.

On Christmas Day 2005, mum, Beth and I travelled the 60 miles to the hospital ward, presents in hand and smiles plastered on our faces, trying in vain to pretend that this was a very normal way for us to spend the holidays.

Dad's Christmas meal was a calorie-laden milkshake down his PEG tube and mum, Beth and I had a sandwich in the icy hospital gardens willing time to stop so that we did not have to leave dad and go home. An evening out to celebrate my promotion ended in tears because it felt so meaningless knowing that Dad could not share it with me.

I vowed never to get married as dad could not walk me down the aisle; and as for having kids? What was the point if dad could not teach them the rules of the rugby pitch or the accompanying songs?

In hindsight, I can see that I was grieving and I am sure what I was feeling was quite normal. We were all stuck in limbo; dad was alive but his spirit was dead. At some point I grew up, gained a little perspective and stopped my self-indulgent moaning. I was grieving for dad, but he was grieving for his whole life and the connections to all of the people that he loved. His pain and loss was a million times worse. It was so clear what he had lost on the surface - his movement, dignity and independence but I think many people underestimated how much our relationships with dad were impacted.

Pre-stroke, Dad and I used spend hours chatting and laughing but all of a sudden he could not speak and had no reason to laugh. We would use the letter board to chat but it was not the same. In time, we started to email as he found it easier, but nothing could replace the enjoyment we both got from our animated arguments over the correct pronouncing of the word 'sloth' and other such silly things. I used to see bits of the 'old' dad in our email exchanges, for instance when he would email me a random grammar lesson and his thoughts on the perils of tautology, one of his pet hates, but my heart would sink with every email because it was not how it used to be. It was not much but it was the best we could do and he was nothing if not a great dad, someone who always tried his best to do right by Beth and me.

A few years post-stroke, dad made it clear that his existence was too painful and he wanted to change the law on assisted dying.

Maybe dad was extraordinary after all. He was never shy of a battle and did one hell of a job leading us to war. We fought for dad's right to die as a family and every hit he took, we felt too; every insult thrown at dad hurt us all. The opposition we received was predictable; we could win tomorrow and the pro-lifers would continue to fight against us using the same arguments over and over. We can see both sides of the argument and appreciate that for some, are real concerns with voluntary euthanasia but we are adamant that with mature conversation and logical reasoning, that they can be overcome; some fragments of opposing groups appear to be so blinkered that nothing will ever change their minds.

On the other more positive hand, the support we received was immense and I really believe it was the hundreds of tweets, emails, comments and letters from strangers that kept dad alive for so long. There are many people that do not necessarily support voluntary euthanasia or think it is a path they would want to go down, but they respected dad's right to self-autonomy and his right to die. That is all we asked.

The media interest we received was overwhelming but when we made the decision to fight our campaign in the public eye, we knew what it meant. We needed the press, if we were to show the world the extent of dad's suffering and the media and its public love nothing more than a tragic story of loss and heartbreak. We were the real deal and the radical nature of what we were fighting for maintained interest.

It has now been more than two months since dad died and life does not feel significantly different. Yes, his room is empty of his wheelchair, hoist and other aids; it looks vacant, feels cold and sort of echoes. It will always be 'dad's room'; it was his home for over five years and the place where he died. Granted, I have not received an email from dad consisting of grammar tips and his views on the English language. But when dad died, that is all I lost; in the latter years our relationship was limited and primarily based online. It was seven years ago that I truly lost my dad and then is when I did the bulk of my grieving, shouting and crying. Sitting by his bedside with my family as he took his last breaths was horrific but we feel an overwhelming sense of relief - for him.

I can see now that the emails and so on do not matter. Tony Nicklinson was my dad; I am his flesh and blood. Like dad, I am opinionated, tactless and outspoken; I am friendly, talkative and work hard. I have inherited dad's inability to dance and his flat feet, as well as his love of cheesy jokes and a heated debate. We both love rugby, although for totally different reasons. I don't need the emails and his physical presence because I have so much more - his memory, his fight and his cause.

Our campaign was, for so long, dad's lifeline and he was so determined to see it through. When he was diagnosed with a chest infection and refused antibiotics, armed with the knowledge that he would die without treatment, is evidence of how unbearable he felt his life had become.

But this is not the end of us.

Mum, Beth and I will continue to fight for his right to die, for our right to die and for anyone else that finds themselves in limbo like dad. Being able to choose the time and manner of your own death should be a fundamental human right for everyone, not just the able-bodied or those with just enough movement to do the deed themselves. So watch this space, because we will continue to campaign and fight; dad may be dead but our campaign to legalise voluntary euthanasia is not.

Lauren Nicklinson is 25 years old and is the eldest daughter of Jane and Tony Nicklinson. She lives and works in Bristol as a PR account manager and has a sister Beth.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.