Shroud of Turin Image not Fake, Say Italian Scientists

Italian scientists say the technology required to fake marks on the enigmatic Shroud of Turin, the supposed burial robe of Christ, would not have been available in medieval times, when sceptics say the shroud was created.

Researchers made the claim after conducting a series of experiments they said proved that the image of Christ on the shroud could not have been faked.

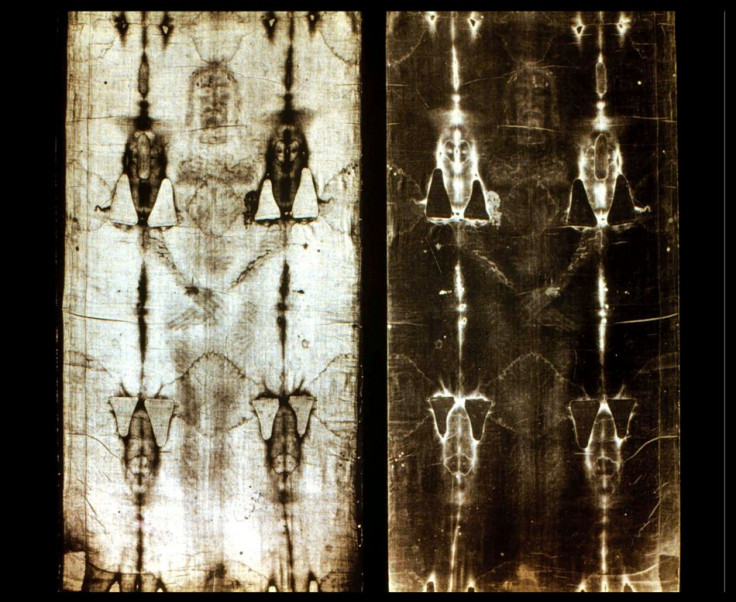

The cloth, bearing the image of a man with what appear to be nail wounds to his wrist and feet, has long been dismissed as a forgery by sceptics. Radiocarbon dating conducted in 1988 in Oxford, Zurich and Arizona suggested that the 5-metre-long shroud was actually made between 1260 and 1390 - at least 1,200 years after Christ was supposedly buried in it.

Those results were disputed on the grounds that the tests were contaminated by fibres from cloth that was used to repair the relic when it was damaged by fire in the Middle Ages.

"The double image front and back of a scourged and crucified man has many physical and chemical characteristics that are so particular that the staining is impossible to obtain in a laboratory," concluded experts from Italy's National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Development.

The scientists set out to "identify the physical and chemical processes capable of generating a colour similar to that of the image on the shroud". They concluded that the particular characteristics of the marks on the cloth could only be produced by pulses of ultraviolet light supplied by lasers - a technology that is only about 80 years old.

They claim that this proves that the image must have been created by "some form of electromagnetic energy".

One of Christianity's most venerated objects, the Turin Shroud has been the subject of intense debate and speculation that has spawned an entire industry of books, research and documentaries.

But the holy implications of the image of the crucified man have led many to draw their own conclusions about where the shroud came from, and many believe the marks on the cloth date from the time of Christ's resurrection.

"We hope our results can open up a philosophical and theological debate but we will leave the conclusions to the experts, and ultimately to the consciousness of individuals," said Professor Paolo di Lazzaro, who led the research.

The Vatican has never officially recognised the shroud as authentic, but the Pope has said that the image "reminds us always" of Jesus's pain and suffering.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.